As the plane land ed at Andrews Air Force Base the nurses on the plane said goodbye to the patients on board. Then the huge loading ramp opened, letting in fresh air and sunlight. After twenty-two hours of darkness and noise I was happy to be stateside but wary of the future.

ed at Andrews Air Force Base the nurses on the plane said goodbye to the patients on board. Then the huge loading ramp opened, letting in fresh air and sunlight. After twenty-two hours of darkness and noise I was happy to be stateside but wary of the future.

A crew of soldiers entered the plane, lifted our stretchers and carried us to buses adapted for stretchers. Not one of the soldiers spoke to us. No “Welcome Home” greetings, no band, nothing.

The bus ride to Walter Reed Army Medical Center took thirty minutes. I expected to be taken to med/surg ward but all the patients were sent to a receiving area,”to be processed,” we were told. I was tired and hungry and in pain,but there were no exceptions: paperwork first.

I was transferred to a gurney. Someone took my medical records. An hour later, someone put an ID band on my wrist. My blood was drawn. Hours passed. Finally, a doctor arrived.

“No malaria,” he said, reading the blood work report. “No need for quinine.” I’d be sent to the proper ward soon.

I asked about the dressing on my thigh. He frowned. Not until Monday. Christ, I thought, it’s the Friday afternoon routine. I really was back in the States.

A Spec/4 handed me my ward assignment. “How do I get there?” I asked. He pointed to a hallway. “Go in that direction. Take the elevator to the fourth floor, make a left at Ward 33.” I said, “No. How am I actually going to get there?” He told me to get my lazy ass off the gurney and to get moving. I told him I hadn’t been out of bed since getting hit and asked for a wheelchair or crutches. He said it wasn’t his job, he was a clerk. I got pissed off and yelled at him. A nurse hurried into the room. Hearing the problem, she glared at the clerk, then found a medic to wheel me away.

The medic, a conscientious objector, said on weekends everyone hoped to leave early. He said there would be more Army BS too. We shook hands at the wards entrance. “Welcome home,” he said.

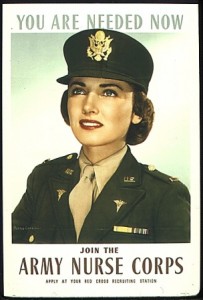

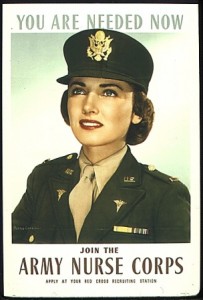

On the large open ward,a nurse came to my bedside. “Do you need anything?” she asked. I told her I was hungry and had pain, and worried about my thigh. It was past dinner time but she ordered me a special meal, and gave me morphine, and changed the dressing too. The wound looked good, she said, applying a new type of gauze. No more ripping and tearing. What a relief! And what a difference from how I was treated earlier that day.

After I had eaten, several patients in wheel chairs came to my bed and welcomed me to the ward. When? they asked, would I have my leg amputated?

“WHAT?? What are you talking about?” I asked. Look around, they said. And I did: every man had lost one or both legs, I was the only one with two. This, they said was the amputation ward. I was sent here to have my leg cut off. I was stunned. Had my worst nightmare come true?

The nurse confirmed my dread. On Monday a doctor would review with me the reason to surgically remove my right leg. “Do you want to call home?” she asked. No, I didn’t. How could I tell my family? And what would I say to Lee? Our plans to marry were shattered. I spent the next forty-eight hours mired in sorrow and self-pity. I had never felt so sad in my life.

On Monday morning I was placed on a gurney and wheeled to a treatment room; the cast on my right leg was cut off. My leg looked awful–so white and withered. Talking in whispers, three doctors poked and prodded its pale white skin.

“What about the amputation,” I asked. The trio seemed puzzled by my question. What amputation? they replied. I told them what the nurse and the patients had said. Dr. Morgan, a major, checked my chart. “Fucking clerks!” he shouted. There had been a mistake. I didn’t need surgery. I had been sent to the wrong ward. Hearing the news, I broke down and cried.

Dr. Morgan said my artery was healed but the problem was my fractured knee. The doctors felt that fusing my leg was the best they could do. It would never heal right, and would be chronically painful and frail. Could the fusion be reversed? I asked. “No,” he said. Then I needed time to think. The doctors agreed to return in an hour.

When we met, I asked about rehabilitation. The other doctors said no, but Dr. Morgan, who outranked them, said yes, and he won out.

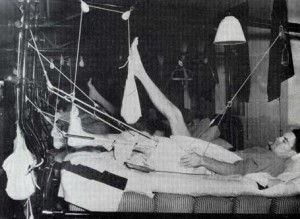

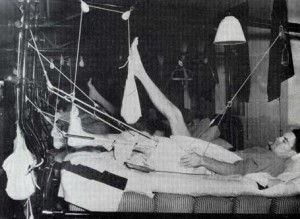

The following day Dr. Morgan said I would spend the next  two months in Buck’s Traction, a weight and pulley device that would straighten my knee by keeping pressure on my lower leg. The healed fracture would be strong enough to walk on. Once the traction was set up, I met Lieutenant David Greathouse, a skilled physical therapist who pushed each man to work hard in his physical recovery.

two months in Buck’s Traction, a weight and pulley device that would straighten my knee by keeping pressure on my lower leg. The healed fracture would be strong enough to walk on. Once the traction was set up, I met Lieutenant David Greathouse, a skilled physical therapist who pushed each man to work hard in his physical recovery.

I met Sgt. Poole, in charge of all non medical matters on Ward 35. He secured pajamas and bathrobes, and socks for cold feet. He had broken TVs fixed or replaced. He resolved discipline problems; pay problems; obtained uniforms for men going home on leave. Under his guidance, the ward was well kept and clean. A lifer, Sgt.Poole would not tolerate disrespect. But if you behaved yourself, he was your best friend.

I made fr iends with Bob Kramer, a red haired man with a broken arm and a fractured femur, and Dale Sturgeon, a thin man with a mangled foot from stepping on a booby trap. “Chevy” Chevaults’ back was broken in a jeep accident. Stephen “Troop” Carter had his leg shredded by a Claymore in a total screw up. Carl had a fractured femur. Caspar was in traction with a broken right leg.

iends with Bob Kramer, a red haired man with a broken arm and a fractured femur, and Dale Sturgeon, a thin man with a mangled foot from stepping on a booby trap. “Chevy” Chevaults’ back was broken in a jeep accident. Stephen “Troop” Carter had his leg shredded by a Claymore in a total screw up. Carl had a fractured femur. Caspar was in traction with a broken right leg.

During my nine months at Walter Reed my friends and I spent twenty-four hours a day together,our beds close enough that we could easily talk without shouting,all of us in the same boat, waiting to heal and go home.

A few days after my arrival, I got a phone call from Lee. I was thrilled to hear her voice and felt on top of the world. We planned to meet that Saturday.

On Saturday morning, I was wheeled to the sun porch, where Lee and I could be alone. At noon, she arrived wearing a bright yellow dress. The moment we saw each other we both wept. Then we hugged and kissed and I told her that when I’m healed and normal, I wanted to marry her. She said, “Yes. Anytime. Any condition. No reservations. Yes.” WOW! I was the luckiest guy in the world! After she left, and I was wheeled back to the ward, I told everyone,“ She said, ‘Yes!’” My buddies cheered my good luck. That evening, when Lee returned, they gave her a celebrities’ welcome. But months would pass before I left the hospital and married her.

Each day on the ward began and ended exactly the same: we were awoken at 7 AM, breakfast was brought to our bedside. Afterward, each man was given a pan of warm water used to shave, brush teeth, and to wash. We relieved ourselves in bedpans, changed into clean pajamas, lay still as medics came and changed the sheets; no easy task with patient in bed. The rest of the morning, sitting upright, we sorted folded and stapled documents, and stuffed addressed, and sealed envelopes. The work was boring and tedious but it helped pass the time.

Each day on the ward began and ended exactly the same: we were awoken at 7 AM, breakfast was brought to our bedside. Afterward, each man was given a pan of warm water used to shave, brush teeth, and to wash. We relieved ourselves in bedpans, changed into clean pajamas, lay still as medics came and changed the sheets; no easy task with patient in bed. The rest of the morning, sitting upright, we sorted folded and stapled documents, and stuffed addressed, and sealed envelopes. The work was boring and tedious but it helped pass the time.

We stopped for lunch at noon. Everyone, officers, enlisted men, staff, ate the same hospital meals. In fact, the meals were quite good, but even better when a notable person was admitted to Walter Reed. During Mamie Eisenhower’s two month convalescence, we ate lobster on Sundays.

Afternoons were spent in a large hall equipped for the demands of physical therapy. This was the most difficult part of our day: re-learning how to walk and lift and stand. It was hard work, and painful, but Lt. Greathouse pushed us to do our best.

Dinner was brought to our bedsides at 5:00 PM. We watched TV most evenings. Officially, it was lights out at 9 PM, but if the volume was kept low, we could watch TV as late as we wished.

On weekends, visitors often spoke to other patients as well as the man they came to see. Church groups brought trays of fresh baked cookies and cake. As did the girls in high school clubs, so pretty and well-dressed, youthful and fragrant. Some men even struck up relationships with them. We were, after all ,only a year or two older than these giggly high school girls.

The wards’ head nurse was a short angry woman with the rank of major. Early one morning she turned on the lights and walked up and down the center aisle, shouti ng obscenities, ranting how ungrateful and uncaring we were. She said the next time one of us felt we were going to die, we must be sure to tell her. That way she would transfer us and we could die somewhere else. Did we know how much paperwork she had to submit when someone died on her ward? Did we? “You gotta be kidding,”I whispered, but Chevy said be quiet, she was for real.

ng obscenities, ranting how ungrateful and uncaring we were. She said the next time one of us felt we were going to die, we must be sure to tell her. That way she would transfer us and we could die somewhere else. Did we know how much paperwork she had to submit when someone died on her ward? Did we? “You gotta be kidding,”I whispered, but Chevy said be quiet, she was for real.

When the major departed, Sgt. Poole informed us that while we slept a patient had died. Do not doubt the major, he said. She would transfer her own dying brother from her ward.

On another occasion, the major walked down the ward pointing to each patient, screaming “You are a disgrace! Your appearance is unacceptable! You need haircuts!” Then, looking at Sgt.Poole, she raised her voice louder and screamed, “Get these men haircuts!” I couldn’t help but laugh out loud. Nearly every man here had been shot or fragged or hit with shrapnel. None of us could walk. So we had long hair! So what! Sgt. Poole said stop laughing, I was making things worse. Carl, his right leg bundled in white plaster, called out, “Mam,we’re sorry for being a disgrace to the Army. The punishment is clear. You should send us back to Vietnam.” Livid, the major said she would personally escort us to the next flight out. Now everyone laughed. Enraged, the major stormed down the center aisle and disappeared.

A barber came to the ward and we got our haircuts, but most of the men had no money to pay. “On the house,” said the barber, raising his hand like a traffic cop. When I had learned to walk, I went to his shop and gave him money. He said this wasn’t the first time the major had pulled that stunt. She didn’t like sick people, he said. He feared her, and thought she was crazy.

The next month, when the major announced her retirement, we clapped and cheered. Everyone was glad but none more so than Sgt. Poole.

Her replacement, Captain Eleanor Salazar, was young and good looking, kind and competent. Because she cared about each of us, we always showed her respect.

The days and weeks passed without incident. Then one evening Sgt. Poole came to my bed and handed me a card board box. He said it contained my personal effects from Vietnam. I was elated at first, but after opening the box I grew sad and bitter. My money, my camera, my First Cav trinkets, all had vanished. Only my photo album remained. I figured somewhere along the line an REMF had looted my stuff. Fucking REMFs.

After six months in traction my leg had straightened out, and I’d learned to walk with crutches. My reward was thirty days leave. I needed an AWOL bag, but the PX was far from the ward, and there were stairs to be climbed from the street. Knowing that I couldn’t make the round trip on crutches, I sat in a wheelchair and rolled forward, my crutches dragging behind.

leave. I needed an AWOL bag, but the PX was far from the ward, and there were stairs to be climbed from the street. Knowing that I couldn’t make the round trip on crutches, I sat in a wheelchair and rolled forward, my crutches dragging behind.

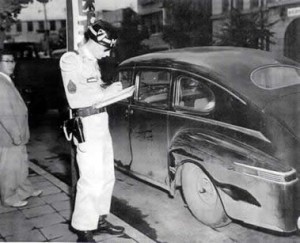

A hundred yards later, I left the wheel chair on the sidewalk, hobbled up the stairs, bought the bag, struggled down the stairs, only to find two MP cars with blue lights flashing.

As I crutched my way to the chair an MP asked if it was mine. I said yes. He said I had caused a pedestrian hazard and gave me a ticket. When I read that I had to appear in a military traffic court the next week, I told him I couldn’t make it, I was going home on leave. “Are you refusing to appear?” he asked. No, I said, I wasn’t refusing, I just couldn’t make it until I got back. The MP said if I didn’t agree to show up in court, he would arrest me.

Just then, Captain Salazar, driving home from work, saw me, pulled over, and asked what was going on. After the MP explained the problem Captain Salazar got out of her car, slammed the door, and thoroughly chewed him out. That was the only time I saw her lose her temper. The ticket was torn up, the MP apologized and, saved by an angel, I rolled away, the crutches dragging noisily behind.

Toward the end of July I was fitted for a leg brace. Since the bone was still healin g, my left shoe was built so that when standing, my right foot did not touch the ground. The next day I went home. I married Lee on August 14, 1970.

g, my left shoe was built so that when standing, my right foot did not touch the ground. The next day I went home. I married Lee on August 14, 1970.

In the months that followed, I began to walk with a cane. Slowly at first, but I was walking, which renewed my hopes for my life with Lee.

By December I had made remarkable progress and a few days before Christmas I bid farewell to Walter Reed. In the summer of ‘71, pending a final review, I was retired from the Army due to injuries sustained in combat.

After being grievously wounded, after a long and painful recovery, my life was turning around. There was only one small detail to complete. By law, until my retirement was final, I had to register with the draft board.

Ruth Starnes, perhaps fifty, was the clerk of the local board. She had wrongly classified me 1A while I was still in high school and refused to correct her mistake. “Too much paperwork,” she said. “Don’t worry about it.”

Five years later, Mrs.Starnes had not changed. She listened intently as I told her the reason for my visit, then went to retrieve my file. When she returned, she had a puzzled look on her face. “What are you doing here? “she said,”You should still be in the Army!”

What? I explained to her that I’d served in Vietnam, had been wounded, and received a medical  retirement. But that didn’t matter to Mrs.Starnes. The problem was that I had not fulfilled my military service. “What are you talking about?” I asked. Mrs. Starnes said I had not completed nineteen months in the Army and that I was attempting to evade military service. She pointed to a small square in my DD 214. I had served eighteen months and seventeen days.

retirement. But that didn’t matter to Mrs.Starnes. The problem was that I had not fulfilled my military service. “What are you talking about?” I asked. Mrs. Starnes said I had not completed nineteen months in the Army and that I was attempting to evade military service. She pointed to a small square in my DD 214. I had served eighteen months and seventeen days.

“Just who was it,” I asked,” who created this rule?”

“Me,”she said. “That’s all that matters.” She said I’d likely be classified 1-A.

Why not IV-A, prior military service, or 4-F,medically unfit for service?” I asked, showing her my records. But Starnes would not accept them. Not mine or anyone elses. “They’re usually phony,” she said.

“Look at me,” I told her. “Look at my leg brace, my cane, my scars.”

Starnes said I could have bought them at any medical supply store. She would wait for the Army to send her my records. In the meantime, I could expect to receive a physical exam notice prior to induction.

“There’s no way I can pass a physical,” I said.“We’ll see,” she replied, then added, “I am sick of you guys trying to get out of your military service obligations.”

“What’s wrong with you?” I asked. Starnes said it would be best for me to leave the office.

I was angry and scared and when I got home I called my Congressman, whose aide said to calm down, he would look into it, and not to worry. A month later I received a new draft card which classified me IV-A, Prior Military Service. Thankfully, I never heard from Starnes again.

Finally, my dealings with the Army were over. I was married, I had a good job, my physical health was improving, at last my life looked good. But a funny thing happened on the way back from war. And it’s lasted for quite some time.

For the first few years, several times a week, I dreamed of being wounded and woke up covered in sweat, my heart racing, my body exhausted.

Wherever I was, if I didn’t feel safe, I kept a look out for troublesome people or places where trouble would likely occur.

Any sharp noise from behind put me on guard. I hated the July 4th.

At work, I could not tolerant sloppiness in anyone, or watch them make mistakes. I would lose my temper and curse them out. Frankly, I was always pissed off, and at anyone who crossed my path.

I was terrified by the unknown. What lay beyond the next corner? And the one after that?

If I smelled something burning I thought of death.

I got angry if anyone thought I was just another crazy Vietnam vet.

For thirty years I convinced myself I didn’t have a problem. Finally, in 2002, I was diagnosed with depression and PTSD. Therapy helps to manage the stress, but I’ll be in counseling the rest of my days.

Well, that’s my story, that’s what happened after I got hit on LZ Frances in Vietnam in 1970. I should have written this down long ago, but kept it hidden, even from myself. Now, it’s no longer trapped inside.

____________

Jeff Motyka served as an RTO with Delta 1/7 First Cavalry Division in 1970.

In the Days After Part 1

In the Days After Part 2

In the Days After Part 3

In the Days After: Part IV

As the plane land ed at Andrews Air Force Base the nurses on the plane said goodbye to the patients on board. Then the huge loading ramp opened, letting in fresh air and sunlight. After twenty-two hours of darkness and noise I was happy to be stateside but wary of the future.

ed at Andrews Air Force Base the nurses on the plane said goodbye to the patients on board. Then the huge loading ramp opened, letting in fresh air and sunlight. After twenty-two hours of darkness and noise I was happy to be stateside but wary of the future.

A crew of soldiers entered the plane, lifted our stretchers and carried us to buses adapted for stretchers. Not one of the soldiers spoke to us. No “Welcome Home” greetings, no band, nothing.

The bus ride to Walter Reed Army Medical Center took thirty minutes. I expected to be taken to med/surg ward but all the patients were sent to a receiving area,”to be processed,” we were told. I was tired and hungry and in pain,but there were no exceptions: paperwork first.

I was transferred to a gurney. Someone took my medical records. An hour later, someone put an ID band on my wrist. My blood was drawn. Hours passed. Finally, a doctor arrived.

“No malaria,” he said, reading the blood work report. “No need for quinine.” I’d be sent to the proper ward soon.

I asked about the dressing on my thigh. He frowned. Not until Monday. Christ, I thought, it’s the Friday afternoon routine. I really was back in the States.

A Spec/4 handed me my ward assignment. “How do I get there?” I asked. He pointed to a hallway. “Go in that direction. Take the elevator to the fourth floor, make a left at Ward 33.” I said, “No. How am I actually going to get there?” He told me to get my lazy ass off the gurney and to get moving. I told him I hadn’t been out of bed since getting hit and asked for a wheelchair or crutches. He said it wasn’t his job, he was a clerk. I got pissed off and yelled at him. A nurse hurried into the room. Hearing the problem, she glared at the clerk, then found a medic to wheel me away.

The medic, a conscientious objector, said on weekends everyone hoped to leave early. He said there would be more Army BS too. We shook hands at the wards entrance. “Welcome home,” he said.

On the large open ward,a nurse came to my bedside. “Do you need anything?” she asked. I told her I was hungry and had pain, and worried about my thigh. It was past dinner time but she ordered me a special meal, and gave me morphine, and changed the dressing too. The wound looked good, she said, applying a new type of gauze. No more ripping and tearing. What a relief! And what a difference from how I was treated earlier that day.

After I had eaten, several patients in wheel chairs came to my bed and welcomed me to the ward. When? they asked, would I have my leg amputated?

“WHAT?? What are you talking about?” I asked. Look around, they said. And I did: every man had lost one or both legs, I was the only one with two. This, they said was the amputation ward. I was sent here to have my leg cut off. I was stunned. Had my worst nightmare come true?

The nurse confirmed my dread. On Monday a doctor would review with me the reason to surgically remove my right leg. “Do you want to call home?” she asked. No, I didn’t. How could I tell my family? And what would I say to Lee? Our plans to marry were shattered. I spent the next forty-eight hours mired in sorrow and self-pity. I had never felt so sad in my life.

On Monday morning I was placed on a gurney and wheeled to a treatment room; the cast on my right leg was cut off. My leg looked awful–so white and withered. Talking in whispers, three doctors poked and prodded its pale white skin.

“What about the amputation,” I asked. The trio seemed puzzled by my question. What amputation? they replied. I told them what the nurse and the patients had said. Dr. Morgan, a major, checked my chart. “Fucking clerks!” he shouted. There had been a mistake. I didn’t need surgery. I had been sent to the wrong ward. Hearing the news, I broke down and cried.

Dr. Morgan said my artery was healed but the problem was my fractured knee. The doctors felt that fusing my leg was the best they could do. It would never heal right, and would be chronically painful and frail. Could the fusion be reversed? I asked. “No,” he said. Then I needed time to think. The doctors agreed to return in an hour.

When we met, I asked about rehabilitation. The other doctors said no, but Dr. Morgan, who outranked them, said yes, and he won out.

The following day Dr. Morgan said I would spend the next two months in Buck’s Traction, a weight and pulley device that would straighten my knee by keeping pressure on my lower leg. The healed fracture would be strong enough to walk on. Once the traction was set up, I met Lieutenant David Greathouse, a skilled physical therapist who pushed each man to work hard in his physical recovery.

two months in Buck’s Traction, a weight and pulley device that would straighten my knee by keeping pressure on my lower leg. The healed fracture would be strong enough to walk on. Once the traction was set up, I met Lieutenant David Greathouse, a skilled physical therapist who pushed each man to work hard in his physical recovery.

I met Sgt. Poole, in charge of all non medical matters on Ward 35. He secured pajamas and bathrobes, and socks for cold feet. He had broken TVs fixed or replaced. He resolved discipline problems; pay problems; obtained uniforms for men going home on leave. Under his guidance, the ward was well kept and clean. A lifer, Sgt.Poole would not tolerate disrespect. But if you behaved yourself, he was your best friend.

I made fr iends with Bob Kramer, a red haired man with a broken arm and a fractured femur, and Dale Sturgeon, a thin man with a mangled foot from stepping on a booby trap. “Chevy” Chevaults’ back was broken in a jeep accident. Stephen “Troop” Carter had his leg shredded by a Claymore in a total screw up. Carl had a fractured femur. Caspar was in traction with a broken right leg.

iends with Bob Kramer, a red haired man with a broken arm and a fractured femur, and Dale Sturgeon, a thin man with a mangled foot from stepping on a booby trap. “Chevy” Chevaults’ back was broken in a jeep accident. Stephen “Troop” Carter had his leg shredded by a Claymore in a total screw up. Carl had a fractured femur. Caspar was in traction with a broken right leg.

During my nine months at Walter Reed my friends and I spent twenty-four hours a day together,our beds close enough that we could easily talk without shouting,all of us in the same boat, waiting to heal and go home.

A few days after my arrival, I got a phone call from Lee. I was thrilled to hear her voice and felt on top of the world. We planned to meet that Saturday.

On Saturday morning, I was wheeled to the sun porch, where Lee and I could be alone. At noon, she arrived wearing a bright yellow dress. The moment we saw each other we both wept. Then we hugged and kissed and I told her that when I’m healed and normal, I wanted to marry her. She said, “Yes. Anytime. Any condition. No reservations. Yes.” WOW! I was the luckiest guy in the world! After she left, and I was wheeled back to the ward, I told everyone,“ She said, ‘Yes!’” My buddies cheered my good luck. That evening, when Lee returned, they gave her a celebrities’ welcome. But months would pass before I left the hospital and married her.

We stopped for lunch at noon. Everyone, officers, enlisted men, staff, ate the same hospital meals. In fact, the meals were quite good, but even better when a notable person was admitted to Walter Reed. During Mamie Eisenhower’s two month convalescence, we ate lobster on Sundays.

Afternoons were spent in a large hall equipped for the demands of physical therapy. This was the most difficult part of our day: re-learning how to walk and lift and stand. It was hard work, and painful, but Lt. Greathouse pushed us to do our best.

Dinner was brought to our bedsides at 5:00 PM. We watched TV most evenings. Officially, it was lights out at 9 PM, but if the volume was kept low, we could watch TV as late as we wished.

On weekends, visitors often spoke to other patients as well as the man they came to see. Church groups brought trays of fresh baked cookies and cake. As did the girls in high school clubs, so pretty and well-dressed, youthful and fragrant. Some men even struck up relationships with them. We were, after all ,only a year or two older than these giggly high school girls.

The wards’ head nurse was a short angry woman with the rank of major. Early one morning she turned on the lights and walked up and down the center aisle, shouti ng obscenities, ranting how ungrateful and uncaring we were. She said the next time one of us felt we were going to die, we must be sure to tell her. That way she would transfer us and we could die somewhere else. Did we know how much paperwork she had to submit when someone died on her ward? Did we? “You gotta be kidding,”I whispered, but Chevy said be quiet, she was for real.

ng obscenities, ranting how ungrateful and uncaring we were. She said the next time one of us felt we were going to die, we must be sure to tell her. That way she would transfer us and we could die somewhere else. Did we know how much paperwork she had to submit when someone died on her ward? Did we? “You gotta be kidding,”I whispered, but Chevy said be quiet, she was for real.

When the major departed, Sgt. Poole informed us that while we slept a patient had died. Do not doubt the major, he said. She would transfer her own dying brother from her ward.

On another occasion, the major walked down the ward pointing to each patient, screaming “You are a disgrace! Your appearance is unacceptable! You need haircuts!” Then, looking at Sgt.Poole, she raised her voice louder and screamed, “Get these men haircuts!” I couldn’t help but laugh out loud. Nearly every man here had been shot or fragged or hit with shrapnel. None of us could walk. So we had long hair! So what! Sgt. Poole said stop laughing, I was making things worse. Carl, his right leg bundled in white plaster, called out, “Mam,we’re sorry for being a disgrace to the Army. The punishment is clear. You should send us back to Vietnam.” Livid, the major said she would personally escort us to the next flight out. Now everyone laughed. Enraged, the major stormed down the center aisle and disappeared.

A barber came to the ward and we got our haircuts, but most of the men had no money to pay. “On the house,” said the barber, raising his hand like a traffic cop. When I had learned to walk, I went to his shop and gave him money. He said this wasn’t the first time the major had pulled that stunt. She didn’t like sick people, he said. He feared her, and thought she was crazy.

The next month, when the major announced her retirement, we clapped and cheered. Everyone was glad but none more so than Sgt. Poole.

Her replacement, Captain Eleanor Salazar, was young and good looking, kind and competent. Because she cared about each of us, we always showed her respect.

The days and weeks passed without incident. Then one evening Sgt. Poole came to my bed and handed me a card board box. He said it contained my personal effects from Vietnam. I was elated at first, but after opening the box I grew sad and bitter. My money, my camera, my First Cav trinkets, all had vanished. Only my photo album remained. I figured somewhere along the line an REMF had looted my stuff. Fucking REMFs.

After six months in traction my leg had straightened out, and I’d learned to walk with crutches. My reward was thirty days leave. I needed an AWOL bag, but the PX was far from the ward, and there were stairs to be climbed from the street. Knowing that I couldn’t make the round trip on crutches, I sat in a wheelchair and rolled forward, my crutches dragging behind.

leave. I needed an AWOL bag, but the PX was far from the ward, and there were stairs to be climbed from the street. Knowing that I couldn’t make the round trip on crutches, I sat in a wheelchair and rolled forward, my crutches dragging behind.

A hundred yards later, I left the wheel chair on the sidewalk, hobbled up the stairs, bought the bag, struggled down the stairs, only to find two MP cars with blue lights flashing.

As I crutched my way to the chair an MP asked if it was mine. I said yes. He said I had caused a pedestrian hazard and gave me a ticket. When I read that I had to appear in a military traffic court the next week, I told him I couldn’t make it, I was going home on leave. “Are you refusing to appear?” he asked. No, I said, I wasn’t refusing, I just couldn’t make it until I got back. The MP said if I didn’t agree to show up in court, he would arrest me.

Just then, Captain Salazar, driving home from work, saw me, pulled over, and asked what was going on. After the MP explained the problem Captain Salazar got out of her car, slammed the door, and thoroughly chewed him out. That was the only time I saw her lose her temper. The ticket was torn up, the MP apologized and, saved by an angel, I rolled away, the crutches dragging noisily behind.

Toward the end of July I was fitted for a leg brace. Since the bone was still healin g, my left shoe was built so that when standing, my right foot did not touch the ground. The next day I went home. I married Lee on August 14, 1970.

g, my left shoe was built so that when standing, my right foot did not touch the ground. The next day I went home. I married Lee on August 14, 1970.

In the months that followed, I began to walk with a cane. Slowly at first, but I was walking, which renewed my hopes for my life with Lee.

By December I had made remarkable progress and a few days before Christmas I bid farewell to Walter Reed. In the summer of ‘71, pending a final review, I was retired from the Army due to injuries sustained in combat.

After being grievously wounded, after a long and painful recovery, my life was turning around. There was only one small detail to complete. By law, until my retirement was final, I had to register with the draft board.

Ruth Starnes, perhaps fifty, was the clerk of the local board. She had wrongly classified me 1A while I was still in high school and refused to correct her mistake. “Too much paperwork,” she said. “Don’t worry about it.”

Five years later, Mrs.Starnes had not changed. She listened intently as I told her the reason for my visit, then went to retrieve my file. When she returned, she had a puzzled look on her face. “What are you doing here? “she said,”You should still be in the Army!”

What? I explained to her that I’d served in Vietnam, had been wounded, and received a medical retirement. But that didn’t matter to Mrs.Starnes. The problem was that I had not fulfilled my military service. “What are you talking about?” I asked. Mrs. Starnes said I had not completed nineteen months in the Army and that I was attempting to evade military service. She pointed to a small square in my DD 214. I had served eighteen months and seventeen days.

retirement. But that didn’t matter to Mrs.Starnes. The problem was that I had not fulfilled my military service. “What are you talking about?” I asked. Mrs. Starnes said I had not completed nineteen months in the Army and that I was attempting to evade military service. She pointed to a small square in my DD 214. I had served eighteen months and seventeen days.

“Just who was it,” I asked,” who created this rule?”

“Me,”she said. “That’s all that matters.” She said I’d likely be classified 1-A.

Why not IV-A, prior military service, or 4-F,medically unfit for service?” I asked, showing her my records. But Starnes would not accept them. Not mine or anyone elses. “They’re usually phony,” she said.

“Look at me,” I told her. “Look at my leg brace, my cane, my scars.”

Starnes said I could have bought them at any medical supply store. She would wait for the Army to send her my records. In the meantime, I could expect to receive a physical exam notice prior to induction.

“There’s no way I can pass a physical,” I said.“We’ll see,” she replied, then added, “I am sick of you guys trying to get out of your military service obligations.”

“What’s wrong with you?” I asked. Starnes said it would be best for me to leave the office.

I was angry and scared and when I got home I called my Congressman, whose aide said to calm down, he would look into it, and not to worry. A month later I received a new draft card which classified me IV-A, Prior Military Service. Thankfully, I never heard from Starnes again.

Finally, my dealings with the Army were over. I was married, I had a good job, my physical health was improving, at last my life looked good. But a funny thing happened on the way back from war. And it’s lasted for quite some time.

For the first few years, several times a week, I dreamed of being wounded and woke up covered in sweat, my heart racing, my body exhausted.

Wherever I was, if I didn’t feel safe, I kept a look out for troublesome people or places where trouble would likely occur.

Any sharp noise from behind put me on guard. I hated the July 4th.

At work, I could not tolerant sloppiness in anyone, or watch them make mistakes. I would lose my temper and curse them out. Frankly, I was always pissed off, and at anyone who crossed my path.

I was terrified by the unknown. What lay beyond the next corner? And the one after that?

If I smelled something burning I thought of death.

I got angry if anyone thought I was just another crazy Vietnam vet.

For thirty years I convinced myself I didn’t have a problem. Finally, in 2002, I was diagnosed with depression and PTSD. Therapy helps to manage the stress, but I’ll be in counseling the rest of my days.

Well, that’s my story, that’s what happened after I got hit on LZ Frances in Vietnam in 1970. I should have written this down long ago, but kept it hidden, even from myself. Now, it’s no longer trapped inside.

____________

Jeff Motyka served as an RTO with Delta 1/7 First Cavalry Division in 1970.

In the Days After Part 1

In the Days After Part 2

In the Days After Part 3