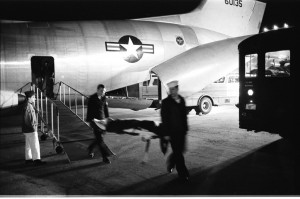

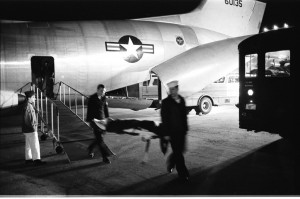

The plane finally landed at Camp Drake in late afternoon. In the distance loomed the rising snow capped peak of Mt. Fuji. Those who could walk exited the aircraft first. Stretchers bearers carefully hoisted the remaining men off the plane. No one spoke. A rumbling caravan of green army buses brought us to the sprawling grounds of the 249th General Hospital.

I was placed on a med/surg ward where dozens of beds filled the room, each occupied by a wounded man. I was surprised to see nurses in starched white uniforms,caps,and white shoes. Instead of Army fatigues, the medics wore blue or white hospital scrubs.

I had pain. All the new men had pain o r discomfort. We’d been carried, lifted and flown from Saigon, then lifted again and bused to the outskirts of Tokyo. When a nurse asked, “Who needs something for pain?” every new patient raised his arm. The nurse reached into her dress pocket, produced a large bottle, from which she gave each man two pills. As we gulped them down she informed us only a skeleton crew was on hand. “On weekends, you’ll need to be patient,” she said. “And quiet.” Noise would not be tolerated. “Use the ear jack,” she told me, pointing to my transistor radio. At 8 PM when the lights went out, I fell immediately asleep.

r discomfort. We’d been carried, lifted and flown from Saigon, then lifted again and bused to the outskirts of Tokyo. When a nurse asked, “Who needs something for pain?” every new patient raised his arm. The nurse reached into her dress pocket, produced a large bottle, from which she gave each man two pills. As we gulped them down she informed us only a skeleton crew was on hand. “On weekends, you’ll need to be patient,” she said. “And quiet.” Noise would not be tolerated. “Use the ear jack,” she told me, pointing to my transistor radio. At 8 PM when the lights went out, I fell immediately asleep.

The next day, two nurses paused at my bedside ,checked my chart, and moved on. “Wait,” I called out. But, answering my question, they said I had no open wounds; all stitches were taken out in Vietnam. And what of the blister burn beneath my cast? Wait until Monday. There was nothing they could do. “Then I’d like to see a doctor,” I said. Emergencies only; and the nurses moved on. My thigh hurt badly; I had no choice but to wait.

On Monday morning, a ward doctor ordered my cast to be cut off. He said Dr. Thomas had been mistaken. “Didn’t he know this would cause your knee to stiffen up?” he asked. In that moment I chose not to reply.

With a noisy hand-held electric saw a medic carefully cut away the layers of plaster which encased my leg. Almost immediately, a terrible stench filled the air. The blister dressing was soaked with pus and putrefied flesh. When a nurse reached over and tried to tear it off, I screamed as I’d never screamed before. Then I grabbed her. “Stop!” I yelled. “Please stop!” Thankfully she did and injected me with morphine. “You’ll have to take the dressing off yourself,” she said. “If you can’t ,we’ll do it.” I tried. I really tried. But it was just too painful.

my leg. Almost immediately, a terrible stench filled the air. The blister dressing was soaked with pus and putrefied flesh. When a nurse reached over and tried to tear it off, I screamed as I’d never screamed before. Then I grabbed her. “Stop!” I yelled. “Please stop!” Thankfully she did and injected me with morphine. “You’ll have to take the dressing off yourself,” she said. “If you can’t ,we’ll do it.” I tried. I really tried. But it was just too painful.

Left alone, for the first time in weeks I looked at my leg. The skin had lost all color and was now a delicate pale white. The muscles I’d gained from tramping on patrols had wasted and shriveled up. The nerve damage resulted in no feeling below my knee. I put my hand over my mouth and shook my head. This couldn’t be true. It just couldn’t. But it was.

An hour passed. The nurse and medic returned. The nurse took one look at the dressing and ordered the medic t o hold my arms. Grabbing the edge of the gauze firmly, she removed it off in a sudden ripping tear. The pain was horrific. I’d never experienced anything like it. When I stopped screaming and shaking and had calmed down I forced myself to inspect the wound. A pool of yellow-green pus poured from a raw fist-sized crater in my withered thigh. Gently, the nurse cleaned and dried it, and slowly, the discharge turned a healthy bright red. A new dressing was applied. From then on, every day for two awful weeks it was rip, tear, rip, tear. All because the Army had screwed up my first cast. I cannot forgive the soldier who did that. I simply can’t.

o hold my arms. Grabbing the edge of the gauze firmly, she removed it off in a sudden ripping tear. The pain was horrific. I’d never experienced anything like it. When I stopped screaming and shaking and had calmed down I forced myself to inspect the wound. A pool of yellow-green pus poured from a raw fist-sized crater in my withered thigh. Gently, the nurse cleaned and dried it, and slowly, the discharge turned a healthy bright red. A new dressing was applied. From then on, every day for two awful weeks it was rip, tear, rip, tear. All because the Army had screwed up my first cast. I cannot forgive the soldier who did that. I simply can’t.

Later that day the ward doctor came to my bedside. A smile played on his lips. He seemed playful, happy, amused. Without a word he touched the top arch of my right foot. Then the left. Then the right again. He looked up and smiled approvingly.

“You’re in very good shape!” he said. “Dr. Thomas was right.” In his spare time he’d read up on Dr. Thomas’ artery repair. “There’s a good chance you’ll keep that leg.” His words filled me with joy. This was my hope, the reason I kept quiet when he had criticized what Dr.Thomas had done.

“I need to make a new cast,” he said,and sent the medic to fetch the materials. “This way, I know it’s made well and set right.”

There is a n art to fixing just the right mixture of warm water and plaster of Paris in a metal surgical tub. There is an art to soaking gauze strips in that mixture and winding and re-winding the saturated cloth, spiraling it up and down the injured limb. There is an art to the smoothing of wet plaster, the cutting of errant loose ends. There is an art to setting the pliant cast so that it hardens just so about the fractured leg or broken hand.

n art to fixing just the right mixture of warm water and plaster of Paris in a metal surgical tub. There is an art to soaking gauze strips in that mixture and winding and re-winding the saturated cloth, spiraling it up and down the injured limb. There is an art to the smoothing of wet plaster, the cutting of errant loose ends. There is an art to setting the pliant cast so that it hardens just so about the fractured leg or broken hand.

The doctor fa shioned a three inch square in the wet plaster. The dressing could now be changed with the cast in place. When he had finished his work, he looked at the white cylindrical mass as if it were art. “Not bad…not bad,” he said, and gently patted my shoulder. This good doctor, whose name I don’t recall, would continue to visit me every day.

shioned a three inch square in the wet plaster. The dressing could now be changed with the cast in place. When he had finished his work, he looked at the white cylindrical mass as if it were art. “Not bad…not bad,” he said, and gently patted my shoulder. This good doctor, whose name I don’t recall, would continue to visit me every day.

The remainder of my time at Camp Drake followed a simple routine: wake up, shave, eat, dressing change, pain meds, lights out. My indispensable radio was my one escape. As well as music, I listened to sports. The broadcast of Ernie Banks hitting his five hundreth home run lifted my spirits. I recall the date well: May 12, 1970.

Three days later, joining a long line of patients,I was loaded onto the largest transport plane I’d ever seen. We stopped in Alaska but due to my injuries I stayed on board. Finally, after twenty-two wearisome hours, we arrived at Andrews Air Force Base. Little did I know how long it would be, the long road home.

_____________

In the Days After Part 4

In The Days After: Part III

The plane finally landed at Camp Drake in late afternoon. In the distance loomed the rising snow capped peak of Mt. Fuji. Those who could walk exited the aircraft first. Stretchers bearers carefully hoisted the remaining men off the plane. No one spoke. A rumbling caravan of green army buses brought us to the sprawling grounds of the 249th General Hospital.

I was placed on a med/surg ward where dozens of beds filled the room, each occupied by a wounded man. I was surprised to see nurses in starched white uniforms,caps,and white shoes. Instead of Army fatigues, the medics wore blue or white hospital scrubs.

I had pain. All the new men had pain o r discomfort. We’d been carried, lifted and flown from Saigon, then lifted again and bused to the outskirts of Tokyo. When a nurse asked, “Who needs something for pain?” every new patient raised his arm. The nurse reached into her dress pocket, produced a large bottle, from which she gave each man two pills. As we gulped them down she informed us only a skeleton crew was on hand. “On weekends, you’ll need to be patient,” she said. “And quiet.” Noise would not be tolerated. “Use the ear jack,” she told me, pointing to my transistor radio. At 8 PM when the lights went out, I fell immediately asleep.

r discomfort. We’d been carried, lifted and flown from Saigon, then lifted again and bused to the outskirts of Tokyo. When a nurse asked, “Who needs something for pain?” every new patient raised his arm. The nurse reached into her dress pocket, produced a large bottle, from which she gave each man two pills. As we gulped them down she informed us only a skeleton crew was on hand. “On weekends, you’ll need to be patient,” she said. “And quiet.” Noise would not be tolerated. “Use the ear jack,” she told me, pointing to my transistor radio. At 8 PM when the lights went out, I fell immediately asleep.

The next day, two nurses paused at my bedside ,checked my chart, and moved on. “Wait,” I called out. But, answering my question, they said I had no open wounds; all stitches were taken out in Vietnam. And what of the blister burn beneath my cast? Wait until Monday. There was nothing they could do. “Then I’d like to see a doctor,” I said. Emergencies only; and the nurses moved on. My thigh hurt badly; I had no choice but to wait.

On Monday morning, a ward doctor ordered my cast to be cut off. He said Dr. Thomas had been mistaken. “Didn’t he know this would cause your knee to stiffen up?” he asked. In that moment I chose not to reply.

With a noisy hand-held electric saw a medic carefully cut away the layers of plaster which encased my leg. Almost immediately, a terrible stench filled the air. The blister dressing was soaked with pus and putrefied flesh. When a nurse reached over and tried to tear it off, I screamed as I’d never screamed before. Then I grabbed her. “Stop!” I yelled. “Please stop!” Thankfully she did and injected me with morphine. “You’ll have to take the dressing off yourself,” she said. “If you can’t ,we’ll do it.” I tried. I really tried. But it was just too painful.

my leg. Almost immediately, a terrible stench filled the air. The blister dressing was soaked with pus and putrefied flesh. When a nurse reached over and tried to tear it off, I screamed as I’d never screamed before. Then I grabbed her. “Stop!” I yelled. “Please stop!” Thankfully she did and injected me with morphine. “You’ll have to take the dressing off yourself,” she said. “If you can’t ,we’ll do it.” I tried. I really tried. But it was just too painful.

Left alone, for the first time in weeks I looked at my leg. The skin had lost all color and was now a delicate pale white. The muscles I’d gained from tramping on patrols had wasted and shriveled up. The nerve damage resulted in no feeling below my knee. I put my hand over my mouth and shook my head. This couldn’t be true. It just couldn’t. But it was.

An hour passed. The nurse and medic returned. The nurse took one look at the dressing and ordered the medic t o hold my arms. Grabbing the edge of the gauze firmly, she removed it off in a sudden ripping tear. The pain was horrific. I’d never experienced anything like it. When I stopped screaming and shaking and had calmed down I forced myself to inspect the wound. A pool of yellow-green pus poured from a raw fist-sized crater in my withered thigh. Gently, the nurse cleaned and dried it, and slowly, the discharge turned a healthy bright red. A new dressing was applied. From then on, every day for two awful weeks it was rip, tear, rip, tear. All because the Army had screwed up my first cast. I cannot forgive the soldier who did that. I simply can’t.

o hold my arms. Grabbing the edge of the gauze firmly, she removed it off in a sudden ripping tear. The pain was horrific. I’d never experienced anything like it. When I stopped screaming and shaking and had calmed down I forced myself to inspect the wound. A pool of yellow-green pus poured from a raw fist-sized crater in my withered thigh. Gently, the nurse cleaned and dried it, and slowly, the discharge turned a healthy bright red. A new dressing was applied. From then on, every day for two awful weeks it was rip, tear, rip, tear. All because the Army had screwed up my first cast. I cannot forgive the soldier who did that. I simply can’t.

Later that day the ward doctor came to my bedside. A smile played on his lips. He seemed playful, happy, amused. Without a word he touched the top arch of my right foot. Then the left. Then the right again. He looked up and smiled approvingly.

“You’re in very good shape!” he said. “Dr. Thomas was right.” In his spare time he’d read up on Dr. Thomas’ artery repair. “There’s a good chance you’ll keep that leg.” His words filled me with joy. This was my hope, the reason I kept quiet when he had criticized what Dr.Thomas had done.

“I need to make a new cast,” he said,and sent the medic to fetch the materials. “This way, I know it’s made well and set right.”

There is a n art to fixing just the right mixture of warm water and plaster of Paris in a metal surgical tub. There is an art to soaking gauze strips in that mixture and winding and re-winding the saturated cloth, spiraling it up and down the injured limb. There is an art to the smoothing of wet plaster, the cutting of errant loose ends. There is an art to setting the pliant cast so that it hardens just so about the fractured leg or broken hand.

n art to fixing just the right mixture of warm water and plaster of Paris in a metal surgical tub. There is an art to soaking gauze strips in that mixture and winding and re-winding the saturated cloth, spiraling it up and down the injured limb. There is an art to the smoothing of wet plaster, the cutting of errant loose ends. There is an art to setting the pliant cast so that it hardens just so about the fractured leg or broken hand.

The doctor fa shioned a three inch square in the wet plaster. The dressing could now be changed with the cast in place. When he had finished his work, he looked at the white cylindrical mass as if it were art. “Not bad…not bad,” he said, and gently patted my shoulder. This good doctor, whose name I don’t recall, would continue to visit me every day.

shioned a three inch square in the wet plaster. The dressing could now be changed with the cast in place. When he had finished his work, he looked at the white cylindrical mass as if it were art. “Not bad…not bad,” he said, and gently patted my shoulder. This good doctor, whose name I don’t recall, would continue to visit me every day.

The remainder of my time at Camp Drake followed a simple routine: wake up, shave, eat, dressing change, pain meds, lights out. My indispensable radio was my one escape. As well as music, I listened to sports. The broadcast of Ernie Banks hitting his five hundreth home run lifted my spirits. I recall the date well: May 12, 1970.

Three days later, joining a long line of patients,I was loaded onto the largest transport plane I’d ever seen. We stopped in Alaska but due to my injuries I stayed on board. Finally, after twenty-two wearisome hours, we arrived at Andrews Air Force Base. Little did I know how long it would be, the long road home.

_____________

In the Days After Part 4