A collection of photo illustrated war and post war vignettes, short stories, war nightmares, war poetry and travel writing by a Vietnam combat medic. Site includes war related videos and documents. There is some harsh language.

A year after leaving the Army, I enrolled at Seton Hall University, a Catholic school which had recently gone co-ed. I was a hippy. My new uniform consisted of blues jeans, a white shirt under a black vest, a pearl in my right ear, and my grimy boonie hat, adorned with love beads, CMB, Cav patch, grenade pins, the word Cambodia inked on the brim. I didn’t talk much that first year. You can bet some people thought I was strange.

The other day I stumbled upon Seton Hall’s online year book archive. Class of ‘76, I’d lost my copy quite some time ago. Bullied in high school about my looks, I refused to be photographed in ’68, and devised a scheme in ’76.

On the day of my sitting, held on the second floor of the white brick student center, I removed my sport jacket, and handed it, a white shirt and tie, to Wally, one of my best friends. We were roughly the same height and had the same lanky build. Wally, who was smart, energetic, and wonderfully witty, was known for his acting ability, and began performing at Seton Hall’s theatre-in-the-round.

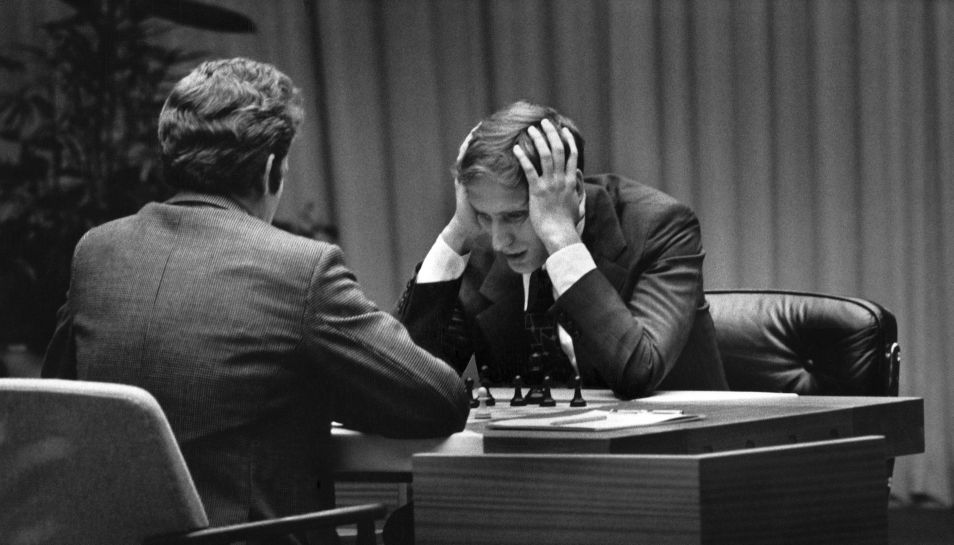

Often, Wally and I spent hours in my large off campus room, playing chess while stoned on pot, or improvising and recording comedy sketches on a wood paneled reel to reel tape deck.

I recall cuing up Eric Satie’s Gymnopedie on a phonograph, and telling Wally, “Think of a skit.” He closed his eyes, dipped his head thoughtfully, concentrated, eyes open, gave me a nod.

As the sad melody poured forth, Wally’s impersonation of an old woman in exile was stunning. “I’m lonesome, son. Biding my time, feeling my years. Heeerrreee, at the Hidden Embarrassment Ooold Folks Home.” And he kept going, a flawless unscripted five minute monolog. How did he do it? I kept those tapes for quite some time.

Wally knew my address and phone number. On the spot the memorized my date of birth, height and weight. Looking spiffy in my sports jacket and tie, he marched up the spiraling stairs, gave me thumbs up, a artful grin, and off he went. But ten minutes later he hurried back, a worried look on his handsome face. Breathless, “What’s your social security number?” he asked. “They want to know. They want it!”

The nine digits memorized, he hurried back to the photographers. Twenty minutes later, a smiling Wally triumphantly handed me the carbon copies of the forms he’d signed and dated. The photo proofs, he said, would be mailed to me in two months. We laughed loudly, but would celebrate later. It was time for class.

When the photo proofs arrived I sent in a check. They sent me a year book. On page 233 of the 1976 Galleon, instead of my face, behold the serious young man, his earnest eyes that peer directly into the camera, his kinky hair neatly trimmed. And beneath the black and white portrait, my name, and BA, Religious Studies.

I recall his last performance. Playing a waiter dressed in fancy tux, a circular tray with two full wine glasses held aloft, Wally swirled and pranced across the stage, somehow never spilling a drop. The audience sat on the edge of their seats, mesmerized.

Over time I saw less of him. Friends said he missed rehearsals. There were rumors. And in 1975, he disappeared.

Ten years later, a phone call. “Long distance,” said the operator. “Will you accept the charges?” Wally was desperate. He needed money. Could not explain. I sent him one hundred dollars. And never heard back.

In 1988 I took a matinee seat in a shabby movie theater in Jersey City, New Jersey. There might have been twenty people in the audience. “Stand and Deliver.” A spiffy title for a film about working class, below grade Hispanic students, an intrepid teacher who sought to improve their lot. Half way through the compelling film, in walked Wally.

Not into the theater, but onto the screen. I nearly jumped from my seat. It was my pal Wally, playing the substantial part of Dr. Pearson, an official sent to investigate the high school students, whose inexplicably high test scores suggested cheating.

I have a vague memory of trying to contact Wally’s folks. His dad was an Air Force officer. His brother had been killed in Vietnam. There was no internet. I had found Wally. And lost him, again.

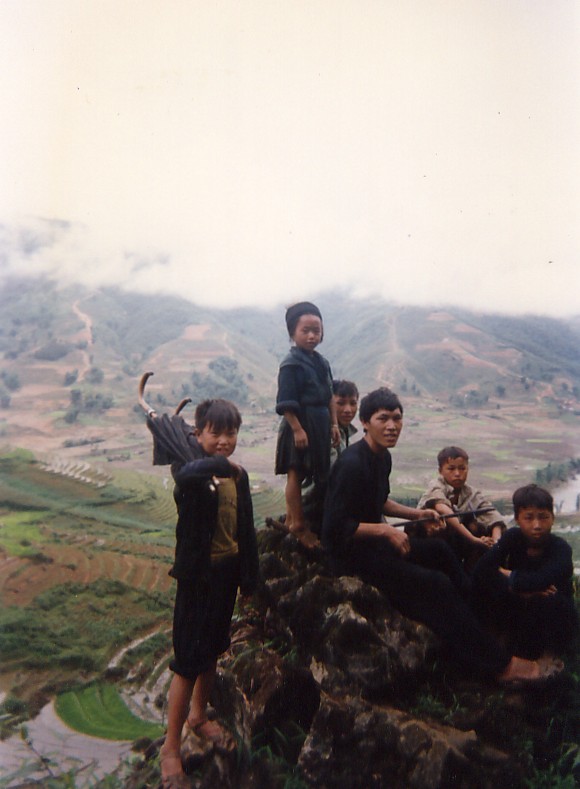

In 1992 it was my turn. I left the United States and backpacked Central America for eight months. Lived in Todos Santos, a mountain village. Spent hours and hours trekking alone, as if on patrol. The few gringos in the village thought I was strange. A year later, I moved to New Zealand. Found work. Saved money. Backpacked Southeast Asia, Indonesia, Australia, Europe. I had many adventures, but many flashbacks in Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam. Eight months later, an insufferable seven weeks on a PTSD ward in Montrose, NY. From ’96 to 2000, I moved 12 times.

In 2001, I located Wally, who now called himself Riff. We spoke by phone. He’d left school to be a professional actor. Through dark times and menial jobs, he kept at it, auditioning at every chance. After four years, he made it. Sit coms, movies, commercials. He’d married, found his place in life. I recall we each choked up. A few weeks later, a card in the mail. A bank check fluttered from it. $1000. “Repayment,” the note said. I hadn’t mentioned the debt. He thought I’d forgot. Riff had a nice place in a spiffy town. I was always welcome to visit.

That was seventeen years ago. We’re both feeling our years. Biding our time. I should call him. Take up the invite. We’ll play chess. Maybe pass a joint. I’m sure we both have things to tell.

My Pal Wally

The other day I stumbled upon Seton Hall’s online year book archive. Class of ‘76, I’d lost my copy quite some time ago. Bullied in high school about my looks, I refused to be photographed in ’68, and devised a scheme in ’76.

On the day of my sitting, held on the second floor of the white brick student center, I removed my sport jacket, and handed it, a white shirt and tie, to Wally, one of my best friends. We were roughly the same height and had the same lanky build. Wally, who was smart, energetic, and wonderfully witty, was known for his acting ability, and began performing at Seton Hall’s theatre-in-the-round.

Often, Wally and I spent hours in my large off campus room, playing chess while stoned on pot, or improvising and recording comedy sketches on a wood paneled reel to reel tape deck.

or improvising and recording comedy sketches on a wood paneled reel to reel tape deck.

I recall cuing up Eric Satie’s Gymnopedie on a phonograph, and telling Wally, “Think of a skit.” He closed his eyes, dipped his head thoughtfully, concentrated, eyes open, gave me a nod.

As the sad melody poured forth, Wally’s impersonation of an old woman in exile was stunning. “I’m lonesome, son. Biding my time, feeling my years. Heeerrreee, at the Hidden Embarrassment Ooold Folks Home.” And he kept going, a flawless unscripted five minute monolog. How did he do it? I kept those tapes for quite some time.

Wally knew my address and phone number. On the spot the memorized my date of birth, height and weight. Looking spiffy in my sports jacket and tie, he marched up the spiraling stairs, gave me thumbs up, a artful grin, and off he went. But ten minutes later he hurried back, a worried look on his handsome face. Breathless, “What’s your social security number?” he asked. “They want to know. They want it!”

The nine digits memorized, he hurried back to the photographers. Twenty minutes later, a smiling Wally triumphantly handed me the carbon copies of the forms he’d signed and dated. The photo proofs, he said, would be mailed to me in two months. We laughed loudly, but would celebrate later. It was time for class.

When the photo proofs arrived I sent in a check. They sent me a year book. On page 233 of the 1976 Galleon, instead of my face, behold the serious young man, his earnest eyes that peer directly into the camera, his kinky hair neatly trimmed. And beneath the black and white portrait, my name, and BA, Religious Studies.

I recall his last performance. Playing a waiter dressed in fancy tux, a circular tray with two full wine glasses held aloft, Wally swirled and pranced across the stage, somehow never spilling a drop. The audience sat on the edge of their seats, mesmerized.

Over time I saw less of him. Friends said he missed rehearsals. There were rumors. And in 1975, he disappeared.

In 1988 I took a matinee seat in a shabby movie theater in Jersey City, New Jersey. There might have been twenty people in the audience. “Stand and Deliver.” A spiffy title for a film about working class, below grade Hispanic students, an intrepid teacher who sought to improve their lot. Half way through the compelling film, in walked Wally.

Not into the theater, but onto the screen. I nearly jumped from my seat. It was my pal Wally, playing the substantial part of Dr. Pearson, an official sent to investigate the high school students, whose inexplicably high test scores suggested cheating.

I have a vague memory of trying to contact Wally’s folks. His dad was an Air Force officer. His brother had been killed in Vietnam. There was no internet. I had found Wally. And lost him, again.

In 1992 it was my turn. I left the United State s and backpacked Central America for eight months. Lived in Todos Santos, a mountain village. Spent hours and hours trekking alone, as if on patrol. The few gringos in the village thought I was strange. A year later, I moved to New Zealand. Found work. Saved money. Backpacked Southeast Asia, Indonesia, Australia, Europe. I had many adventures, but many flashbacks in Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam. Eight months later, an insufferable seven weeks on a PTSD ward in Montrose, NY. From ’96 to 2000, I moved 12 times.

s and backpacked Central America for eight months. Lived in Todos Santos, a mountain village. Spent hours and hours trekking alone, as if on patrol. The few gringos in the village thought I was strange. A year later, I moved to New Zealand. Found work. Saved money. Backpacked Southeast Asia, Indonesia, Australia, Europe. I had many adventures, but many flashbacks in Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam. Eight months later, an insufferable seven weeks on a PTSD ward in Montrose, NY. From ’96 to 2000, I moved 12 times.

In 2001, I located Wally, who now called himself Riff. We spoke by phone. He’d left school to be a professional actor. Through dark times and menial jobs, he kept at it, auditioning at every chance. After four years, he made it. Sit coms, movies, commercials. He’d married, found his place in life. I recall we each choked up. A few weeks later, a card in the mail. A bank check fluttered from it. $1000. “Repayment,” the note said. I hadn’t mentioned the debt. He thought I’d forgot. Riff had a nice place in a spiffy town. I was always welcome to visit.

That was seventeen years ago. We’re both feeling our years. Biding our time. I should call him. Take up the invite. We’ll play chess. Maybe pass a joint. I’m sure we both have things to tell.

_____________