Near midnight, the helicopter landed at 3rd Field Hospital. I was the sole passenger. Stretcher bearers carried me to a large med/surge ward that was dark and quiet.

In a warm soothing voice a nurse asked me, “How are you? How was your flight?” “Fine,” I said, a bit taken aback. She had been told my dad and I were VIPs. I decided not to argue the point. “You’ll be treated well here,” she said. I asked if she could do something for the pain. Even with the full casts my wounds were acting up. She nodded and gave me a morphine shot. Instantly I felt warm and relaxed and soon drifted to sleep. What a difference from the endless hassles at the 24th Evac.

In a warm soothing voice a nurse asked me, “How are you? How was your flight?” “Fine,” I said, a bit taken aback. She had been told my dad and I were VIPs. I decided not to argue the point. “You’ll be treated well here,” she said. I asked if she could do something for the pain. Even with the full casts my wounds were acting up. She nodded and gave me a morphine shot. Instantly I felt warm and relaxed and soon drifted to sleep. What a difference from the endless hassles at the 24th Evac.

The next morning I was given a razor, shaving cream, a toothbrush, toothpaste a comb, and a basin of hot water. “You can keep them,” said the nurse.

In fact, these were the only things I now possessed. My M16 and pack, my grenades, ammo and water, all were gone, left on the battlefield or lost in transit.

After I washed up a second nurse brought me clean pajamas. A medic brought me scrambled eggs and toast. Was this real? Was I dreaming? But I soon realized that all fifty patients on the ward were treated with the same dignity and care.

There was more good news. Although I still had malaria, my blood was drawn just once a day.

At nine o’clock my dad appeared and came to my bed. We were overjoyed at the sight of each other,and I know he wanted to hug me and kiss me, b ut in front of the patients and nurses we just shook hands.

ut in front of the patients and nurses we just shook hands.

I could hear the nurse telling the patients what was happening. They were in awe and disbelief. But my dad not only visited me each day I was here, he spoke with each wounded man on the ward. Once home, he called their parents to ease their worries. They too had gotten the dread telegram from the Secretary of the Army. I was glad and proud to share my dad with other men recovering from their wounds.

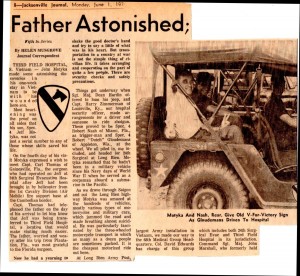

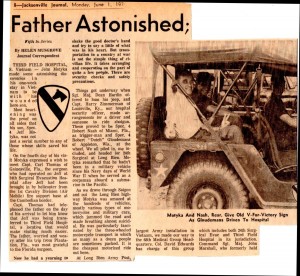

An hour or two after my father arrived a red haired woman wearing jungle fatigues came to my bed. My dad introduced her as Helen “Patches” Musgrave. She wore a boonie hat and her combat fatigues were covered with unit patches from every branch of the service. Patches, a reporter from Florida, said she wanted to write about me and my Dad. She said the 1st Cav claimed this was the first time a parent had ever visited a wounded son in Vietnam.

An hour or two after my father arrived a red haired woman wearing jungle fatigues came to my bed. My dad introduced her as Helen “Patches” Musgrave. She wore a boonie hat and her combat fatigues were covered with unit patches from every branch of the service. Patches, a reporter from Florida, said she wanted to write about me and my Dad. She said the 1st Cav claimed this was the first time a parent had ever visited a wounded son in Vietnam.

A half hour later, Sgt. Jim Sanders joined us. “Do you need anything,” he asked. I told him a transistor radio would be much appreciated. Sgt. Sanders took my Dad to the PX and told the staff Dad could buy anything he wanted, anytime. The portable radio he bought became my prized possession. For the next week Dad and Patches visited me twice a day. Alone with my dad, we talked about many things.

Each day I felt myself making progress. My wounds were healing and the malaria was easing up. I felt stronger, my thoughts were clearer, I had less pain. I truly enjoyed the company of my Dad. For the first time in a long time I felt safe.

After eight days I was scheduled to fly to Japan. I was taken to a special room where medic’s wrapped me in a cast from below my waist to my entire right leg, and from below the knee on my entire left leg. “Packaging for shipment,” they called it. This would keep me stable, protecting the fracture and Dr. Thomas’s crucial arterial repair.

The very next day I was bused to a staging hospital at Tan So Nhut airport. After being off loaded, I was  greeted by three attractive Air Force nurses wearing dress uniforms. Perfume. They had on perfume. My dad, Patches and a Lt. Rodriguez arrived soon afterward. Lt. Rodriguez presented me with an Army Commendation Medal with V device for actions on LZ Frances the day I was hit. Back at 24th Evac,General Elvy Roberts gave me a Bronze Star with V for the exact same event. I figured this was for the benefit of my Dad,so I smiled, saluted,

greeted by three attractive Air Force nurses wearing dress uniforms. Perfume. They had on perfume. My dad, Patches and a Lt. Rodriguez arrived soon afterward. Lt. Rodriguez presented me with an Army Commendation Medal with V device for actions on LZ Frances the day I was hit. Back at 24th Evac,General Elvy Roberts gave me a Bronze Star with V for the exact same event. I figured this was for the benefit of my Dad,so I smiled, saluted,

and shook hands. Patches had us pose for pictures. After lunch I said goodbye to my Dad. It would be many months before I saw him again.

Resting up from my busy day, I noticed the nurses had changed into fatigues. When I asked why, they explained that higher ups had ordered dress uniforms on account of my Dad, and in case we were photographed. They said nothing like this had ever happened before. I said I was sorry and they understood; it was about the important visitor, his son,and the stories to be written by Patches. Oddly, all her pictures were fuzzy and out of focus.

Resting up from my busy day, I noticed the nurses had changed into fatigues. When I asked why, they explained that higher ups had ordered dress uniforms on account of my Dad, and in case we were photographed. They said nothing like this had ever happened before. I said I was sorry and they understood; it was about the important visitor, his son,and the stories to be written by Patches. Oddly, all her pictures were fuzzy and out of focus.

The next morning one hundred patients were carefully loaded onto a large plane. Our stretchers were stacked four high, and there were four rows of stretchers, one along each side of the plane, two rows down the middle. The huge cabin had no windows. From where I lay at floor level, I could see and hear nurses talking with patients, and checking their charts. The aisles were crowded with medical equipment. With the plane finally loaded, the engines roared, the plane sped down the runway, abruptly lifted and took off.

I thought,“Goodbye Vietnam!” but onboard there were no cheers or clapping or whoops of joy. There was only the engines constant dull drone, which made it hard to talk. The nurses might have sedated us. Nearly everyone fell asleep at the same time; we woke that afternoon in Japan. Up until now the days of the week meant nothing to me. They were numbers to be scratched off my short timer’s calender. Each day was one less day in Vietnam. One day closer to home. My time in Vietnam had ended; I was still in the Army, but today was Friday, my first day in Japan.

Addenda

Obituary: Helen “Patches” Musgrave

In his excellent book War Stories Conrad Leighton, a reporter for the First Cavalry in 1970-71, knew Musgrave personally, and describes her as a well-intentioned patriot with little insight into herself, the war, or those against it.

______________

In the Days After Part 3

In the Days After Part 4

In The Days After: Part II

Near midnight, the helicopter landed at 3rd Field Hospital. I was the sole passenger. Stretcher bearers carried me to a large med/surge ward that was dark and quiet.

The next morning I was given a razor, shaving cream, a toothbrush, toothpaste a comb, and a basin of hot water. “You can keep them,” said the nurse.

In fact, these were the only things I now possessed. My M16 and pack, my grenades, ammo and water, all were gone, left on the battlefield or lost in transit.

After I washed up a second nurse brought me clean pajamas. A medic brought me scrambled eggs and toast. Was this real? Was I dreaming? But I soon realized that all fifty patients on the ward were treated with the same dignity and care.

There was more good news. Although I still had malaria, my blood was drawn just once a day.

At nine o’clock my dad appeared and came to my bed. We were overjoyed at the sight of each other,and I know he wanted to hug me and kiss me, b ut in front of the patients and nurses we just shook hands.

ut in front of the patients and nurses we just shook hands.

I could hear the nurse telling the patients what was happening. They were in awe and disbelief. But my dad not only visited me each day I was here, he spoke with each wounded man on the ward. Once home, he called their parents to ease their worries. They too had gotten the dread telegram from the Secretary of the Army. I was glad and proud to share my dad with other men recovering from their wounds.

A half hour later, Sgt. Jim Sanders joined us. “Do you need anything,” he asked. I told him a transistor radio would be much appreciated. Sgt. Sanders took my Dad to the PX and told the staff Dad could buy anything he wanted, anytime. The portable radio he bought became my prized possession. For the next week Dad and Patches visited me twice a day. Alone with my dad, we talked about many things.

Each day I felt myself making progress. My wounds were healing and the malaria was easing up. I felt stronger, my thoughts were clearer, I had less pain. I truly enjoyed the company of my Dad. For the first time in a long time I felt safe.

After eight days I was scheduled to fly to Japan. I was taken to a special room where medic’s wrapped me in a cast from below my waist to my entire right leg, and from below the knee on my entire left leg. “Packaging for shipment,” they called it. This would keep me stable, protecting the fracture and Dr. Thomas’s crucial arterial repair.

The very next day I was bused to a staging hospital at Tan So Nhut airport. After being off loaded, I was greeted by three attractive Air Force nurses wearing dress uniforms. Perfume. They had on perfume. My dad, Patches and a Lt. Rodriguez arrived soon afterward. Lt. Rodriguez presented me with an Army Commendation Medal with V device for actions on LZ Frances the day I was hit. Back at 24th Evac,General Elvy Roberts gave me a Bronze Star with V for the exact same event. I figured this was for the benefit of my Dad,so I smiled, saluted,

greeted by three attractive Air Force nurses wearing dress uniforms. Perfume. They had on perfume. My dad, Patches and a Lt. Rodriguez arrived soon afterward. Lt. Rodriguez presented me with an Army Commendation Medal with V device for actions on LZ Frances the day I was hit. Back at 24th Evac,General Elvy Roberts gave me a Bronze Star with V for the exact same event. I figured this was for the benefit of my Dad,so I smiled, saluted,

and shook hands. Patches had us pose for pictures. After lunch I said goodbye to my Dad. It would be many months before I saw him again.

The next morning one hundred patients were carefully loaded onto a large plane. Our stretchers were stacked four high, and there were four rows of stretchers, one along each side of the plane, two rows down the middle. The huge cabin had no windows. From where I lay at floor level, I could see and hear nurses talking with patients, and checking their charts. The aisles were crowded with medical equipment. With the plane finally loaded, the engines roared, the plane sped down the runway, abruptly lifted and took off.

I thought,“Goodbye Vietnam!” but onboard there were no cheers or clapping or whoops of joy. There was only the engines constant dull drone, which made it hard to talk. The nurses might have sedated us. Nearly everyone fell asleep at the same time; we woke that afternoon in Japan. Up until now the days of the week meant nothing to me. They were numbers to be scratched off my short timer’s calender. Each day was one less day in Vietnam. One day closer to home. My time in Vietnam had ended; I was still in the Army, but today was Friday, my first day in Japan.

Addenda

Obituary: Helen “Patches” Musgrave

In his excellent book War Stories Conrad Leighton, a reporter for the First Cavalry in 1970-71, knew Musgrave personally, and describes her as a well-intentioned patriot with little insight into herself, the war, or those against it.

______________

In the Days After Part 3

In the Days After Part 4