At twenty-one, James Aalund was not a lucky man. As he looked out a bunker port during a mortar attack, a round exploded and blew his head off. Medic did not know James but still recalls the wounded men screaming into the radio,“ Dead man! We have a dead man!”

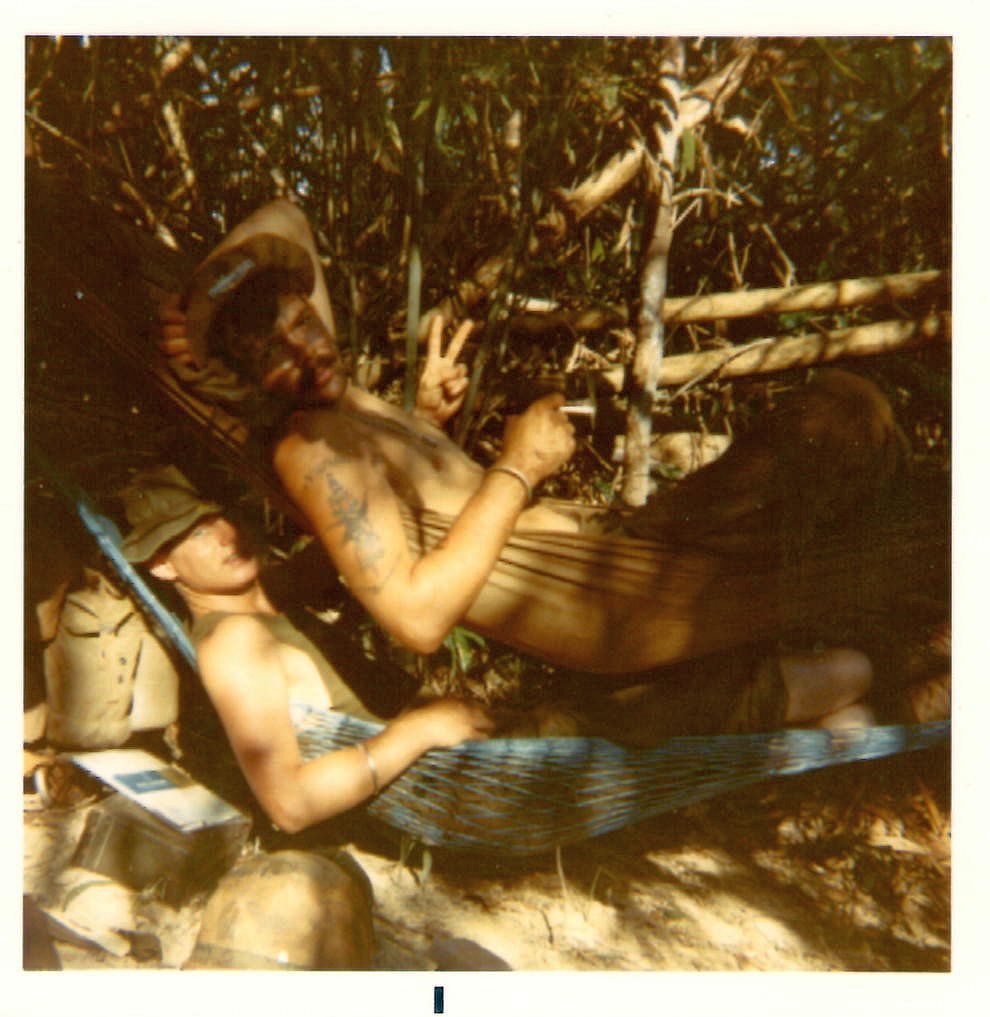

Some months later,after a similar attack, Jeff Motyka fared better.“Doc,” he called, as our eyes met inside a sweltering aid station. Supported by two grunts, a moment later Jeff fainted from loss of blood. Forty-three years later he told me what happened in the days after he was hit.

I was medevaced to 24th Surgical Evac in Long Binh, lifted on to a gurney, and raced into an emergency room. The poncho covering me was removed. I was naked. The morphine had worn off. “Please don’t hurt me,” I said. A female nurse asked for my name, rank and social security number. Another nurse had to insert a catheter into my bladder. “This is going to hurt,” she said. “Close your eyes and take deep breathes.” She had good news. No blood in my urine.

I was medevaced to 24th Surgical Evac in Long Binh, lifted on to a gurney, and raced into an emergency room. The poncho covering me was removed. I was naked. The morphine had worn off. “Please don’t hurt me,” I said. A female nurse asked for my name, rank and social security number. Another nurse had to insert a catheter into my bladder. “This is going to hurt,” she said. “Close your eyes and take deep breathes.” She had good news. No blood in my urine.

I’m wheeled to X-ray. My body is full of shrapnel. My leg is fractured. I plead for morphine. “Not yet,” they say. I’m wheeled into an operating room. A tall thin man in blue scrubs introduces himself as Dr.Thomas, United States Air Force. “I’ll be your surgeon. You have shrapnel in your stomach. The femur is fractured at the knee.” He doesn’t know if that will be fixed today. He will treat the shrap wounds and whatever else he finds.

“Where are you from, soldier?” he asked ,and smiled when I said Fort Lauderdale. “Me too,” he said. We make small talk. I ask for pain meds. “You don’t need any. Breathe deep,” he says,” and count backward from one hundred.”

“Where are you from, soldier?” he asked ,and smiled when I said Fort Lauderdale. “Me too,” he said. We make small talk. I ask for pain meds. “You don’t need any. Breathe deep,” he says,” and count backward from one hundred.”

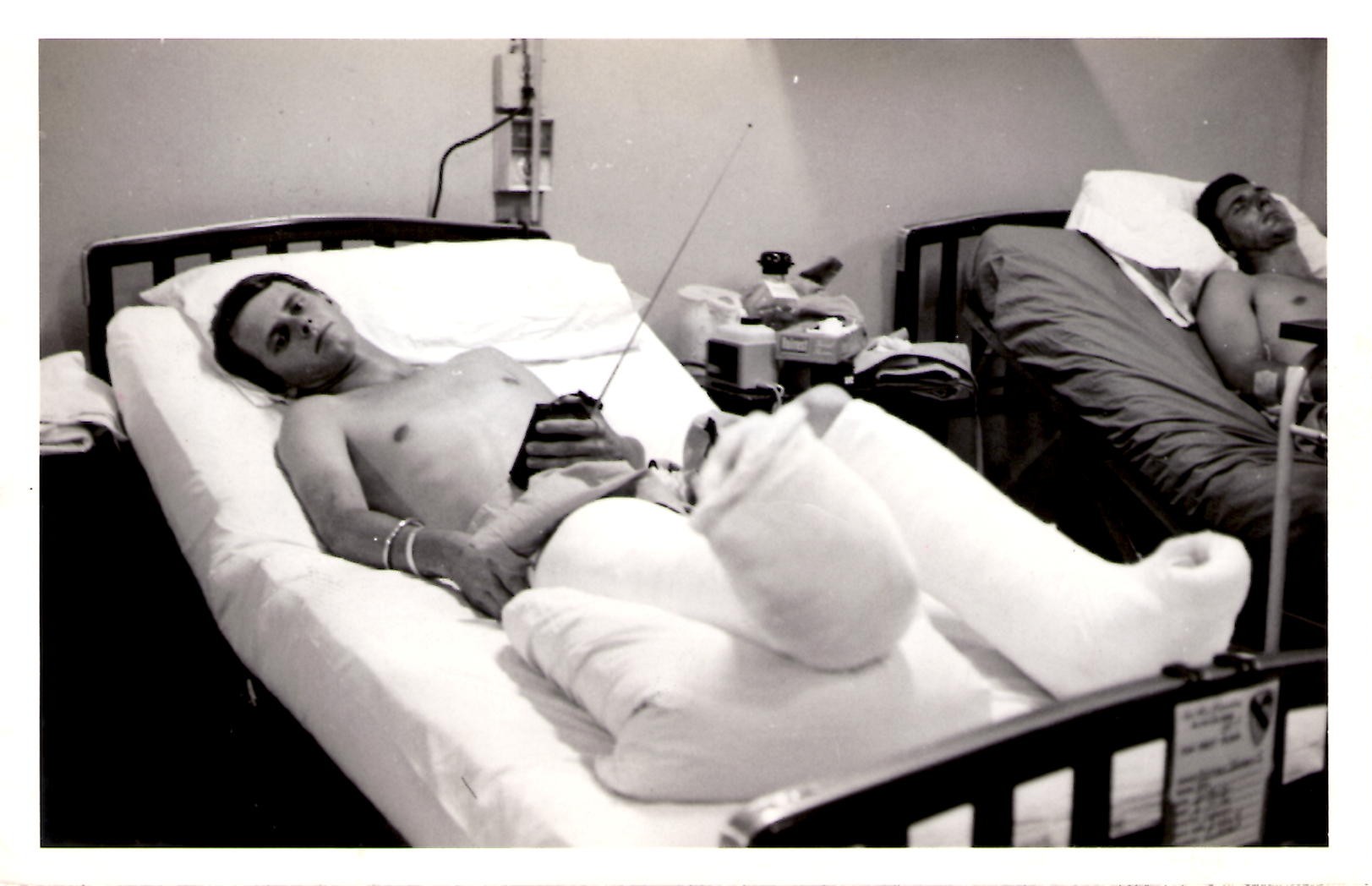

When I woke up,naked beneath a white sheet, my right leg was in cast. The catheter was still in place. A feeding tube snaked down my nose to my throat. I had IVs in both arms. My belly was bandaged. I fell back to sleep.

In the morning I hear the shrill voice of a middle aged staff sergeant yelling, “Wake up!”I stare at this man dressed in new, starched, jungle fatigues. He’s wearing glasses, a handle bar mustache. He’s over-weight. “Clean up!” he shouts. What does he mean? I look around the air conditioned ward. A dozen beds line each wall; a nurses station occupies the center aisle. All the patients are bed ridden.

The Sergeant came to my bedside. “When was the last time you shaved?” he asked. When I told him I didn’t know he grew angry. My appearance was a disgrace. Handing me an electric razor, he said “Now shave.” My arms were heavily bandaged;both had IVs. After several failed attempts, he took the razor back and shaved me. He said I’m still in the Army, not at summer camp. “From now on, he said, “Shave every morning.” In a loud voice he told the ward,” My job is to get you people returned to your units. There will be no hanging around here. Malingering will not be tolerated.” With that he walked away.

I told him I didn’t know he grew angry. My appearance was a disgrace. Handing me an electric razor, he said “Now shave.” My arms were heavily bandaged;both had IVs. After several failed attempts, he took the razor back and shaved me. He said I’m still in the Army, not at summer camp. “From now on, he said, “Shave every morning.” In a loud voice he told the ward,” My job is to get you people returned to your units. There will be no hanging around here. Malingering will not be tolerated.” With that he walked away.

Breakfast arrived but I was ordered not to eat. An hour later Dr. Thomas had good news: he’d sewn up my intestines. The bad: he couldn’t fix my knee fracture. He said I had nerve damage, and tested my reflexes. I couldn’t feel or lift my right foot. Dr. Thomas said in time it would improve.

The shrap in my knee had damaged an important artery; Dr. Thomas performed micro surgery to repair it; he’d bent my leg at angle before setting it in a cast. Other army doctors would be critical, but this assured the artery healed right. If all went well (the repair could fail–amputation would follow) I’d need traction and physical therapy for a very long time. We shook hands. Then Dr. Thomas was off to his next patient.

The shrap in my knee had damaged an important artery; Dr. Thomas performed micro surgery to repair it; he’d bent my leg at angle before setting it in a cast. Other army doctors would be critical, but this assured the artery healed right. If all went well (the repair could fail–amputation would follow) I’d need traction and physical therapy for a very long time. We shook hands. Then Dr. Thomas was off to his next patient.

Not long afterward the Sergeant and a female nurse came to remove my catheter. The Sergeant warned, “Don’t wet the bed.” But I did. This was not uncommon but the Sergeant grew angry. The nurse,a lieutenant by rank,ordered him to change my sheets. He went about it roughly. In the days ahead I met other staff who were tender and caring

The following day I learned about wound  care. Shrapnel wounds, dirty and large compared to bullet holes, can be one or two inches deep. Due to the blast, shrap wounds are imbedded with metal, cloth and dirt. A surgeon removes the visible metal and debris. The wound is left open, not stitched shut. Debriedment is the process of packing the wound with gauze; removing it daily; repacking with new gauze. The removal is agony. The blood soaked cotton has dried and attached itself to the healing tissue; removing the gauze tears open the wound,which causes bleeding that flushes out debris and putrid skin. When the gauze is yanked off, everyone screams bloody murder. The wound is irrigated and rubbed dry. Heal, tear, heal, tear. It’s fucking agony.

care. Shrapnel wounds, dirty and large compared to bullet holes, can be one or two inches deep. Due to the blast, shrap wounds are imbedded with metal, cloth and dirt. A surgeon removes the visible metal and debris. The wound is left open, not stitched shut. Debriedment is the process of packing the wound with gauze; removing it daily; repacking with new gauze. The removal is agony. The blood soaked cotton has dried and attached itself to the healing tissue; removing the gauze tears open the wound,which causes bleeding that flushes out debris and putrid skin. When the gauze is yanked off, everyone screams bloody murder. The wound is irrigated and rubbed dry. Heal, tear, heal, tear. It’s fucking agony.

Each morning,the nurses make their way down the aisle, stopping at each bed to debried a wound. One by one, like clock work, the patients groan and scream. By the time it’s my turn I’m terrified. Don’t hurt me. Don’t hurt me. But they always do.

When I curse from pain the Sergeant says, “If you want sympathy you’re in the wrong place. Act like a man.” He says next time I’ll get an Article 15.

I’m not a day out of combat; my head spins in a million directions, I’m in agony and scared and don’t know what to do, and this guy threatens me with an Article 15?

Finally, after the dressings are cleansed, I’m injected with morphine. It kicks in fast. The drug is wonderfully warm and soothing and kills the pain. I feel like I’m drifting on a river of air. It’s so beautiful. I will never forget the bliss of being without pain.

Finally, after the dressings are cleansed, I’m injected with morphine. It kicks in fast. The drug is wonderfully warm and soothing and kills the pain. I feel like I’m drifting on a river of air. It’s so beautiful. I will never forget the bliss of being without pain.

Seven days later I’m back in surgery. When I wake up, my shrap wounds are closed, sutured shut with stainless steel thread. They say it’s easier to keep clean. Maybe that’s true, but it hurts like hell.

After my blood is drawn the following day, the Sergeant says,“You got malaria. Have you been taking your malaria pills?” I tell him I never missed a dose. “You’re lying,” he says, and tells me I might be court martialed. But Dr. Thomas overhears him and says I probably got it from the six pint blood transfusion. The Sergeant is flustered, he is pissed.

On my tenth day, a ward doctor tells me to breathe more deeply to inflate my lungs, otherwise I’ll get pneumonia. I tell him I can’t. Breathing hard hurts. He knows that my belly was opened to remove shrap and repair my intestines,but he keeps at it: I better be coughing by 6 PM. I try. The pain is unbearable.

When the doctor returns, I cough for him. “Not good enough,” he says, and tells me to look at the ceiling. He inserts a needle under my Adam’s apple, slowly pushes the plunger, and drips saline down my throat. I feel like I’m drowning. The pain is incredible but I can’t stop coughing. Finally, he removes the needle. “I told you I could make you cough,”he says, happy with himself. He warns me to cough every hour or he’ll do it again. I look away, then look down at the sheet. There’s blood on it. Five sutures have split apart. I beg for morphine. The nurse is annoyed; she has to re-stitch me. The Sergeant glares. I can’t believe this is happening. I just can’t believe it.

Twice a day, a physical therapist comes to my bed. Michael is pleasant and takes care not to hurt me. When he does, he’s sorry, and lightens his touch. He always asks if I hurt anywhere. One day I tell him, “My right thigh.” The Sergeant, who is watching, says the tissue is intact. But Michael wants to look under my cast. The Sergeant reviews my chart. “Nothing,” he says. “Must be phantom pain.” That afternoon I tell Michael it still hurts. The Sergeant hands Michael new X-rays: there is no shrap visible. But when Michael pushes his fingers under the cast I scream bloody murder. He says the skin is hot. He tells the Sergeant the splint must be loosened. Angered, the Sergeant finds a medic who pries the cast up. “Oh, my god,” says Michael. “He’s burned.”He calls for Dr. Thomas.

pleasant and takes care not to hurt me. When he does, he’s sorry, and lightens his touch. He always asks if I hurt anywhere. One day I tell him, “My right thigh.” The Sergeant, who is watching, says the tissue is intact. But Michael wants to look under my cast. The Sergeant reviews my chart. “Nothing,” he says. “Must be phantom pain.” That afternoon I tell Michael it still hurts. The Sergeant hands Michael new X-rays: there is no shrap visible. But when Michael pushes his fingers under the cast I scream bloody murder. He says the skin is hot. He tells the Sergeant the splint must be loosened. Angered, the Sergeant finds a medic who pries the cast up. “Oh, my god,” says Michael. “He’s burned.”He calls for Dr. Thomas.

Livid, Dr. Thomas explains that after the cast material is soaked in water and molded to the limb, a chemical reaction occurs. Whoever made my cast didn’t trim the excess, but folded it beneath my thigh. The multiplied heat caused a severe burn, which had become infected.

Dr. Thomas lectured the Sergeant in front of the entire ward. “Stop being lazy,” he said, “and listen to patients. Phantom pain? Nonsense.” The Sergeant turned red and walked out,never to be seen again.

Five days later a Red Cross worker asked if I’m ready for my one free call home. “Sure,” I said, elated.

A heavy black telephone was brought to me. When I picked up the receiver I heard my mother’s voice. I told her I was OK. I asked about my Dad. She said he was on his way to Vietnam, his company had arranged the trip. I was stunned. My Dad coming to see me in Vietnam? Can he just travel to 24th Evac? I didn’t tell the patients or nurses or Dr. Thomas. They wouldn’t have believed me.

A heavy black telephone was brought to me. When I picked up the receiver I heard my mother’s voice. I told her I was OK. I asked about my Dad. She said he was on his way to Vietnam, his company had arranged the trip. I was stunned. My Dad coming to see me in Vietnam? Can he just travel to 24th Evac? I didn’t tell the patients or nurses or Dr. Thomas. They wouldn’t have believed me.

At ten that night, a medic came to my bed. “Who are you?” he asked. Several nurses and officers repeated the question. “I’m just a soldier,” I said.

“Is your dad a Senator? A Congressman? An Ambassador? Who is he?” When I said he was just a regular guy, they said no,he had to be someone important. They said my Dad is in Saigon. They said I’m leaving for Saigon in twenty minutes.

Why were they dressing me in light blue pajamas? I’ve been naked since April 23rd. They said Army regs, but they’d been ignoring them. Too inconvenient. They said don’t mention that. I’m so happy, I tell them, OK, I’ll keep quiet. And I stay quiet forty-three years.

I’m placed on a gurney, loaded onto a bird and flown to Third Field Hospital in Saigon. The pilots say they’ve never done anything like this. “Who is your dad?” they ask. “He must really be important.”

I just smile.

_______________

In the Days After Part 2

In the Days After Part 3

In the Days After Part 4

In the Days After

At twenty-one, James Aalund was not a lucky man. As he looked out a bunker port during a mortar attack, a round exploded and blew his head off. Medic did not know James but still recalls the wounded men screaming into the radio,“ Dead man! We have a dead man!”

Some months later,after a similar attack, Jeff Motyka fared better.“Doc,” he called, as our eyes met inside a sweltering aid station. Supported by two grunts, a moment later Jeff fainted from loss of blood. Forty-three years later he told me what happened in the days after he was hit.

I’m wheeled to X-ray. My body is full of shrapnel. My leg is fractured. I plead for morphine. “Not yet,” they say. I’m wheeled into an operating room. A tall thin man in blue scrubs introduces himself as Dr.Thomas, United States Air Force. “I’ll be your surgeon. You have shrapnel in your stomach. The femur is fractured at the knee.” He doesn’t know if that will be fixed today. He will treat the shrap wounds and whatever else he finds.

When I woke up,naked beneath a white sheet, my right leg was in cast. The catheter was still in place. A feeding tube snaked down my nose to my throat. I had IVs in both arms. My belly was bandaged. I fell back to sleep.

In the morning I hear the shrill voice of a middle aged staff sergeant yelling, “Wake up!”I stare at this man dressed in new, starched, jungle fatigues. He’s wearing glasses, a handle bar mustache. He’s over-weight. “Clean up!” he shouts. What does he mean? I look around the air conditioned ward. A dozen beds line each wall; a nurses station occupies the center aisle. All the patients are bed ridden.

The Sergeant came to my bedside. “When was the last time you shaved?” he asked. When I told him I didn’t know he grew angry. My appearance was a disgrace. Handing me an electric razor, he said “Now shave.” My arms were heavily bandaged;both had IVs. After several failed attempts, he took the razor back and shaved me. He said I’m still in the Army, not at summer camp. “From now on, he said, “Shave every morning.” In a loud voice he told the ward,” My job is to get you people returned to your units. There will be no hanging around here. Malingering will not be tolerated.” With that he walked away.

I told him I didn’t know he grew angry. My appearance was a disgrace. Handing me an electric razor, he said “Now shave.” My arms were heavily bandaged;both had IVs. After several failed attempts, he took the razor back and shaved me. He said I’m still in the Army, not at summer camp. “From now on, he said, “Shave every morning.” In a loud voice he told the ward,” My job is to get you people returned to your units. There will be no hanging around here. Malingering will not be tolerated.” With that he walked away.

Breakfast arrived but I was ordered not to eat. An hour later Dr. Thomas had good news: he’d sewn up my intestines. The bad: he couldn’t fix my knee fracture. He said I had nerve damage, and tested my reflexes. I couldn’t feel or lift my right foot. Dr. Thomas said in time it would improve.

Not long afterward the Sergeant and a female nurse came to remove my catheter. The Sergeant warned, “Don’t wet the bed.” But I did. This was not uncommon but the Sergeant grew angry. The nurse,a lieutenant by rank,ordered him to change my sheets. He went about it roughly. In the days ahead I met other staff who were tender and caring

The following day I learned about wound care. Shrapnel wounds, dirty and large compared to bullet holes, can be one or two inches deep. Due to the blast, shrap wounds are imbedded with metal, cloth and dirt. A surgeon removes the visible metal and debris. The wound is left open, not stitched shut. Debriedment is the process of packing the wound with gauze; removing it daily; repacking with new gauze. The removal is agony. The blood soaked cotton has dried and attached itself to the healing tissue; removing the gauze tears open the wound,which causes bleeding that flushes out debris and putrid skin. When the gauze is yanked off, everyone screams bloody murder. The wound is irrigated and rubbed dry. Heal, tear, heal, tear. It’s fucking agony.

care. Shrapnel wounds, dirty and large compared to bullet holes, can be one or two inches deep. Due to the blast, shrap wounds are imbedded with metal, cloth and dirt. A surgeon removes the visible metal and debris. The wound is left open, not stitched shut. Debriedment is the process of packing the wound with gauze; removing it daily; repacking with new gauze. The removal is agony. The blood soaked cotton has dried and attached itself to the healing tissue; removing the gauze tears open the wound,which causes bleeding that flushes out debris and putrid skin. When the gauze is yanked off, everyone screams bloody murder. The wound is irrigated and rubbed dry. Heal, tear, heal, tear. It’s fucking agony.

Each morning,the nurses make their way down the aisle, stopping at each bed to debried a wound. One by one, like clock work, the patients groan and scream. By the time it’s my turn I’m terrified. Don’t hurt me. Don’t hurt me. But they always do.

When I curse from pain the Sergeant says, “If you want sympathy you’re in the wrong place. Act like a man.” He says next time I’ll get an Article 15.

I’m not a day out of combat; my head spins in a million directions, I’m in agony and scared and don’t know what to do, and this guy threatens me with an Article 15?

Seven days later I’m back in surgery. When I wake up, my shrap wounds are closed, sutured shut with stainless steel thread. They say it’s easier to keep clean. Maybe that’s true, but it hurts like hell.

After my blood is drawn the following day, the Sergeant says,“You got malaria. Have you been taking your malaria pills?” I tell him I never missed a dose. “You’re lying,” he says, and tells me I might be court martialed. But Dr. Thomas overhears him and says I probably got it from the six pint blood transfusion. The Sergeant is flustered, he is pissed.

On my tenth day, a ward doctor tells me to breathe more deeply to inflate my lungs, otherwise I’ll get pneumonia. I tell him I can’t. Breathing hard hurts. He knows that my belly was opened to remove shrap and repair my intestines,but he keeps at it: I better be coughing by 6 PM. I try. The pain is unbearable.

When the doctor returns, I cough for him. “Not good enough,” he says, and tells me to look at the ceiling. He inserts a needle under my Adam’s apple, slowly pushes the plunger, and drips saline down my throat. I feel like I’m drowning. The pain is incredible but I can’t stop coughing. Finally, he removes the needle. “I told you I could make you cough,”he says, happy with himself. He warns me to cough every hour or he’ll do it again. I look away, then look down at the sheet. There’s blood on it. Five sutures have split apart. I beg for morphine. The nurse is annoyed; she has to re-stitch me. The Sergeant glares. I can’t believe this is happening. I just can’t believe it.

Twice a day, a physical therapist comes to my bed. Michael is pleasant and takes care not to hurt me. When he does, he’s sorry, and lightens his touch. He always asks if I hurt anywhere. One day I tell him, “My right thigh.” The Sergeant, who is watching, says the tissue is intact. But Michael wants to look under my cast. The Sergeant reviews my chart. “Nothing,” he says. “Must be phantom pain.” That afternoon I tell Michael it still hurts. The Sergeant hands Michael new X-rays: there is no shrap visible. But when Michael pushes his fingers under the cast I scream bloody murder. He says the skin is hot. He tells the Sergeant the splint must be loosened. Angered, the Sergeant finds a medic who pries the cast up. “Oh, my god,” says Michael. “He’s burned.”He calls for Dr. Thomas.

pleasant and takes care not to hurt me. When he does, he’s sorry, and lightens his touch. He always asks if I hurt anywhere. One day I tell him, “My right thigh.” The Sergeant, who is watching, says the tissue is intact. But Michael wants to look under my cast. The Sergeant reviews my chart. “Nothing,” he says. “Must be phantom pain.” That afternoon I tell Michael it still hurts. The Sergeant hands Michael new X-rays: there is no shrap visible. But when Michael pushes his fingers under the cast I scream bloody murder. He says the skin is hot. He tells the Sergeant the splint must be loosened. Angered, the Sergeant finds a medic who pries the cast up. “Oh, my god,” says Michael. “He’s burned.”He calls for Dr. Thomas.

Livid, Dr. Thomas explains that after the cast material is soaked in water and molded to the limb, a chemical reaction occurs. Whoever made my cast didn’t trim the excess, but folded it beneath my thigh. The multiplied heat caused a severe burn, which had become infected.

Dr. Thomas lectured the Sergeant in front of the entire ward. “Stop being lazy,” he said, “and listen to patients. Phantom pain? Nonsense.” The Sergeant turned red and walked out,never to be seen again.

Five days later a Red Cross worker asked if I’m ready for my one free call home. “Sure,” I said, elated.

At ten that night, a medic came to my bed. “Who are you?” he asked. Several nurses and officers repeated the question. “I’m just a soldier,” I said.

“Is your dad a Senator? A Congressman? An Ambassador? Who is he?” When I said he was just a regular guy, they said no,he had to be someone important. They said my Dad is in Saigon. They said I’m leaving for Saigon in twenty minutes.

Why were they dressing me in light blue pajamas? I’ve been naked since April 23rd. They said Army regs, but they’d been ignoring them. Too inconvenient. They said don’t mention that. I’m so happy, I tell them, OK, I’ll keep quiet. And I stay quiet forty-three years.

I’m placed on a gurney, loaded onto a bird and flown to Third Field Hospital in Saigon. The pilots say they’ve never done anything like this. “Who is your dad?” they ask. “He must really be important.”

I just smile.

_______________

In the Days After Part 2

In the Days After Part 3

In the Days After Part 4