The taxi from Phnom Penh to Kampong Cham took four hours and cost two dollars; the road back was mined. I found a guide, Japro,who spoke good English. Proud owner of a beat-up Honda cub Japro had thick black hair, large white teeth, was thin, talkative, nervous. A survivor of Pol Pot’s killing fields, he smiled when I said, “Five bucks a day, all you can eat.”

The next morning we boarded a crowded ferry made of sheet metal welded to fifty-five gallon  barrels, the flimsy craft powered by a jury-rigged diesel engine.Thirty minutes later, after disembarking, Japro patted the bike’s seat, I hopped on, clenched my legs tight, turned my baseball cap backwards, tied a red bandana over my mouth, and gripped his belt with both hands. Dust and dirt kicked up behind us as we sped past villager’s who waved and laughed.

barrels, the flimsy craft powered by a jury-rigged diesel engine.Thirty minutes later, after disembarking, Japro patted the bike’s seat, I hopped on, clenched my legs tight, turned my baseball cap backwards, tied a red bandana over my mouth, and gripped his belt with both hands. Dust and dirt kicked up behind us as we sped past villager’s who waved and laughed.

“Let’s go to the French rubber plantation,” I shouted over the hot dry wind and the engines roar.

Japro leaned backward. The words “Khmer Rouge” shot past me.

“No,”I sai d, “That’s not true. C’mon, I’ll pay extra.” The thought of danger was magnetic.

d, “That’s not true. C’mon, I’ll pay extra.” The thought of danger was magnetic.

After twenty minutes Japro slowed down, then pulled to the side of the road.

“OK…OK…we are here,” he said.

Before us, in every direction, tall slender rubber trees stood in endless silent rows. The morning sunlight trickled through ten thousand branches and delicate green leaves. We gaped in awe, then dismounted.

Japro pushed the bike like a baby carriage along the muddy trail that led into the rubber tree plantation. All around us,thousands of latex pearls dripped slowly down winding paths carefully etched in the trees’ soft bark. Near the base of each tree small plastic cups collected the raw latex. In war time they were porcelain.

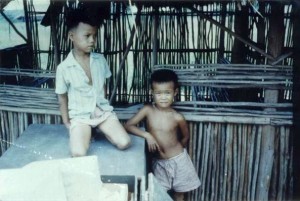

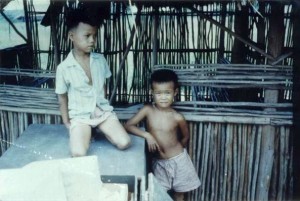

After a time we came across two Cambodian boys who clung precariously to an old Chinese bicycle. Japro spoke softly to them in Khmer. The boys set the bike down, came close, shyly pointed at my white skin, then giggled as they touched the strange brown hair. Vietnamese children had once done the same.

“What wrong?” asked Japro.

“Nothing,”I said. “Let’s go.”

Further on, a sleepy guard in a torn blue uniform dozed against a spiraling tree. Curled in his lap, a wood stocked AK-47, its spear-like bayonet tucked beneath the pitted barrel.

Alerted by our steps, the guard startled awake. There were no Khmer Rouge in the area, he said. He only shot thieves.

We joined him on the forest floor. The air was still and stiflingly hot. No one spoke. In the distance I heard a jingling sound which came closer and closer. Moments later a small wooden cart pulled by a black Cambodian horse in a belled harness came into view. A bright-eyed little girl in colorful rags gripped both reins in one hand. The horse trotted past; it seemed to be happy.

The guard pointed east. He spoke in Khmer.

“They go to factory,” said Japro. Playfully, the guard aimed at the girl with his rifle.

Bidding him goodbye, walking the same path, we followed the tiny hoof prints, the thin lines of the wagon wheels, the receding sound of the jingling bells.

Twenty m inutes later, salted by sweat ,splattered with mud, I caught sight of a one story cinder block building.

inutes later, salted by sweat ,splattered with mud, I caught sight of a one story cinder block building.

“Let’s go in,” I said.

“Maybe not good,” said Japro.

But I paid him no mind.

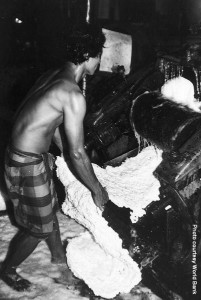

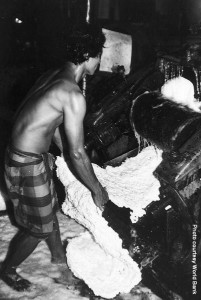

Inside the noisy building I inhaled swirling chemical fumes, kept clear of snapping conveyor belts, chopping gears,snarling engines. The toiling workers, dressed in blue cotton uniforms, completely ignored us.

Processed latex has the speckled look of kapok,the feel of spongy granite: it is hard and thick and unforgiving. I tried cutting a chunk from a heavy square block stacked in a corner.

After gouging and prodding with all my strength I ripped off a chunk the size of an ear.

“You keep?” asked Japro.

“You keep?” asked Japro.

He looked puzzled, as if he were thinking, “What a strange souvenir.”

“Yes,” I said, contemplating the rubbery ball.

But in war time men called such severed things…trophies.

Trophies

The taxi from Phnom Penh to Kampong Cham took four hours and cost two dollars; the road back was mined. I found a guide, Japro,who spoke good English. Proud owner of a beat-up Honda cub Japro had thick black hair, large white teeth, was thin, talkative, nervous. A survivor of Pol Pot’s killing fields, he smiled when I said, “Five bucks a day, all you can eat.”

The next morning we boarded a crowded ferry made of sheet metal welded to fifty-five gallon barrels, the flimsy craft powered by a jury-rigged diesel engine.Thirty minutes later, after disembarking, Japro patted the bike’s seat, I hopped on, clenched my legs tight, turned my baseball cap backwards, tied a red bandana over my mouth, and gripped his belt with both hands. Dust and dirt kicked up behind us as we sped past villager’s who waved and laughed.

barrels, the flimsy craft powered by a jury-rigged diesel engine.Thirty minutes later, after disembarking, Japro patted the bike’s seat, I hopped on, clenched my legs tight, turned my baseball cap backwards, tied a red bandana over my mouth, and gripped his belt with both hands. Dust and dirt kicked up behind us as we sped past villager’s who waved and laughed.

“Let’s go to the French rubber plantation,” I shouted over the hot dry wind and the engines roar.

Japro leaned backward. The words “Khmer Rouge” shot past me.

“No,”I sai d, “That’s not true. C’mon, I’ll pay extra.” The thought of danger was magnetic.

d, “That’s not true. C’mon, I’ll pay extra.” The thought of danger was magnetic.

After twenty minutes Japro slowed down, then pulled to the side of the road.

“OK…OK…we are here,” he said.

Before us, in every direction, tall slender rubber trees stood in endless silent rows. The morning sunlight trickled through ten thousand branches and delicate green leaves. We gaped in awe, then dismounted.

Japro pushed the bike like a baby carriage along the muddy trail that led into the rubber tree plantation. All around us,thousands of latex pearls dripped slowly down winding paths carefully etched in the trees’ soft bark. Near the base of each tree small plastic cups collected the raw latex. In war time they were porcelain.

After a time we came across two Cambodian boys who clung precariously to an old Chinese bicycle. Japro spoke softly to them in Khmer. The boys set the bike down, came close, shyly pointed at my white skin, then giggled as they touched the strange brown hair. Vietnamese children had once done the same.

“What wrong?” asked Japro.

“Nothing,”I said. “Let’s go.”

Further on, a sleepy guard in a torn blue uniform dozed against a spiraling tree. Curled in his lap, a wood stocked AK-47, its spear-like bayonet tucked beneath the pitted barrel.

Alerted by our steps, the guard startled awake. There were no Khmer Rouge in the area, he said. He only shot thieves.

We joined him on the forest floor. The air was still and stiflingly hot. No one spoke. In the distance I heard a jingling sound which came closer and closer. Moments later a small wooden cart pulled by a black Cambodian horse in a belled harness came into view. A bright-eyed little girl in colorful rags gripped both reins in one hand. The horse trotted past; it seemed to be happy.

The guard pointed east. He spoke in Khmer.

“They go to factory,” said Japro. Playfully, the guard aimed at the girl with his rifle.

Bidding him goodbye, walking the same path, we followed the tiny hoof prints, the thin lines of the wagon wheels, the receding sound of the jingling bells.

Twenty m inutes later, salted by sweat ,splattered with mud, I caught sight of a one story cinder block building.

inutes later, salted by sweat ,splattered with mud, I caught sight of a one story cinder block building.

“Let’s go in,” I said.

“Maybe not good,” said Japro.

But I paid him no mind.

Inside the noisy building I inhaled swirling chemical fumes, kept clear of snapping conveyor belts, chopping gears,snarling engines. The toiling workers, dressed in blue cotton uniforms, completely ignored us.

Processed latex has the speckled look of kapok,the feel of spongy granite: it is hard and thick and unforgiving. I tried cutting a chunk from a heavy square block stacked in a corner.

After gouging and prodding with all my strength I ripped off a chunk the size of an ear.

He looked puzzled, as if he were thinking, “What a strange souvenir.”

“Yes,” I said, contemplating the rubbery ball.

But in war time men called such severed things…trophies.