Delta 1/7 Cav grunt Jeff Motyka spent many months in hospital after being severely wounded on LZ Francis. Here, he describes his days and nights in Vietnam. First published in 2600, The Hacker Quarterly,Vol 32, Number 4, 2016.

Radio Telephone Operator. Sounds like a cushy job. Air conditioned office. 8 AM to 5 PM. Monday through Friday. Nights, weekends, and holidays off. Not even close.

Radio Telephone Operator. Sounds like a cushy job. Air conditioned office. 8 AM to 5 PM. Monday through Friday. Nights, weekends, and holidays off. Not even close.

The US Army sent me to Viet Nam in 1969. I served as a combat infantryman, a rifleman, assigned to the Second Platoon of Company D, 1st Battalion, Seventh Cavalry, First Cavalry Division. During my first two months I was just another grunt humping the boonies. I had always been detail-oriented, and drew the diagrams when we set up automatic ambushes.

An AA consisted of several claymore mines linked by det cord; they exploded when a simple tripwire device was touched. My job was to record where each Claymore was placed and where the tripwire and the blasting caps and ignition flare were located. My sketch would be used the next morning to locate and safely disable the mines. This attention to detail put me in line to become the next radio telephone operator (RTO for short) when that man was either wounded, killed, or completed his tour and went home.

In an infantry platoon of twenty men, there is a platoon leader, usually a lieutenant, and a platoon sergeant. Each has an RTO assigned exclusively to him for commo. The radios the RTO’s carry are the lifeline to other platoons, the company commander, medevacs, artillery support, gunships, and resupply. There is no formal training other than observing an radio operator for a day or two. The rest is learned on the job.

In late February 1970 Delta company was on LZ Compton, a remote fire base in  Song Be province, when the NVA launched a ferocious mortar attack. The platoon command bunker took a direct hit. One man was killed and six were wounded. Among the dead and wounded was the acting platoon leader, the new platoon sergeant, and both their RTO’s.

Song Be province, when the NVA launched a ferocious mortar attack. The platoon command bunker took a direct hit. One man was killed and six were wounded. Among the dead and wounded was the acting platoon leader, the new platoon sergeant, and both their RTO’s.

The next day our new platoon leader, a fresh faced 2nd lieutenant, arrived, and I became his RTO. The first thing I had to learn was the Army/NATO phonetic alphabet, where each letter is represented by a specific word. A/Alpha, B/Bravo, C/Charlie, and so on. Words are used instead of letters to avoid confusion with letters that sound alike.

The next task was to learn the specific identifiers for the company. The company commander was “6”. Each platoon leader was designated by the platoon number and then 6. The first platoon leader was 1-6, the second platoon leader was 2-6. Each platoon sergeant was “5”. So, the second platoon sergeant was 2-5, and so on. Each RTO was designated as “India”. So, the company commander’s RTO was 6-India. As the 2nd platoon leader’s radio man, I was 2-6-India. Our platoon sergeant’s RTO was 2-5-India. This may sound confusing, but it was logical, made sense, and learned quickly.

As the RTO, I attached myself to the lieutenant, carrying the radio on my back, attached to my ruck sack. The PRC-25 (pronounced ‘prick’) was the Army’s first solid state FM backpack radio. By today’s standards it was big and heavy. With an operating distance of three to seven miles, it weighed about twenty-five pounds, was approximately four and a half inches thick, twelve inches wide, and about eighteen inches long. The metal cladding was olive green. There was a black corded handset, similar to an old phone. Several topside dials changed the frequencies on which we communicated. The frequencies were changed randomly, though often in the middle of the night. Since it would be totally dark, the second dial could be preset to change by feel. Most often, a small, flexible, whip antenna, about 2 and a half feet long, protruded from the top of the radio. Occasionally we used a ten foot folding antennae to increase the radio signal. However, it was so tall and rigid we used it only after settling in one place.

As the RTO, I attached myself to the lieutenant, carrying the radio on my back, attached to my ruck sack. The PRC-25 (pronounced ‘prick’) was the Army’s first solid state FM backpack radio. By today’s standards it was big and heavy. With an operating distance of three to seven miles, it weighed about twenty-five pounds, was approximately four and a half inches thick, twelve inches wide, and about eighteen inches long. The metal cladding was olive green. There was a black corded handset, similar to an old phone. Several topside dials changed the frequencies on which we communicated. The frequencies were changed randomly, though often in the middle of the night. Since it would be totally dark, the second dial could be preset to change by feel. Most often, a small, flexible, whip antenna, about 2 and a half feet long, protruded from the top of the radio. Occasionally we used a ten foot folding antennae to increase the radio signal. However, it was so tall and rigid we used it only after settling in one place.

The PRC-25 was water resistant. I never totally submerged it—I don’t know if it would still operate after being waterlogged, but we RTOs did our best to keep it dry when crossing rivers or streams. The hand set was thought to be easily damaged by water. When it rained, we wrapped it in plastic, which didn’t interfere with commo. I could walk through most jungle conditions with no problems. On occasion, we used a folding antenna, about ten feet long, which increased the frequency strength, but it was so tall and rigid it could only be used when we settled in place. Considering everything I encountered, I felt confident with the radio. I never experienced a situation when the PRC-25 did not work. The radio took on water, dust, dirt, heat, bumps, bangs, and drops, and never failed.

Regulations required changing the battery daily. Weighing three pounds, and three  to four inches thick, the oblong blocks clicked into place in a protective compartment which shielded them from wind and rain. Once the new battery was installed, the old battery was destroyed. In relatively safe areas, we smashed the battery with a shovel or a rock, or hacked it with a machete. Otherwise, two wires in the battery were pulled out and attached together. This caused the battery to short out, rendering it useless to the enemy, who had their own booby traps.

to four inches thick, the oblong blocks clicked into place in a protective compartment which shielded them from wind and rain. Once the new battery was installed, the old battery was destroyed. In relatively safe areas, we smashed the battery with a shovel or a rock, or hacked it with a machete. Otherwise, two wires in the battery were pulled out and attached together. This caused the battery to short out, rendering it useless to the enemy, who had their own booby traps.

In the jungle, we were re-supplied by helicopters every three days or so. Each radio man received three new batteries. Immediately, we replaced the old one. The other two went into our packs. Due to the additional weight, RTO’s did not carry Claymore mines and M60 machine gun ammunition, which every man, except the medic, did.

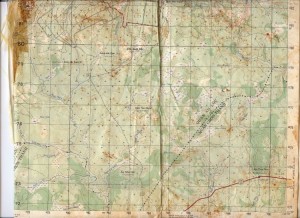

On patrol, I walked directly behind the platoon leader, the radio strapped to my ruck, passing him the handset as needed. This allowed him to receive and transmit orders while moving forward. Whenever we stopped to set up a temporary position, the platoon leader would determine our location on his topo map and give me the latitude and longitude coordinates. Using a code book, I would convert them to letters. Since the code book had different alpha-numeric conversions for each day, and each twelve-hour portion of the day, it was critical to locate the right conversion page.

After I made the conversion, and double checked it with the platoon sergeant, I would radio the company commander’s RTO, speaking to him in code. For example, I would say: “6 India, this is 2-6 India. Our location is Juliet Mike Golf Delta Victor Sierra Romeo. I say again, Juliet Mike Golf Delta Victor Sierra Romeo.” (On the radio, the word “repeat” was used only to request artillery fire at exactly the same coordinates multiple times.) 6 India would then read back the code to me for confirmation. He would then transmit all platoon coordinates to an artillery crew on a firebase five to ten miles away.

After I made the conversion, and double checked it with the platoon sergeant, I would radio the company commander’s RTO, speaking to him in code. For example, I would say: “6 India, this is 2-6 India. Our location is Juliet Mike Golf Delta Victor Sierra Romeo. I say again, Juliet Mike Golf Delta Victor Sierra Romeo.” (On the radio, the word “repeat” was used only to request artillery fire at exactly the same coordinates multiple times.) 6 India would then read back the code to me for confirmation. He would then transmit all platoon coordinates to an artillery crew on a firebase five to ten miles away.

If we came under attack, I would call in our encrypted coordinates for artillery fire, confident that my codes were correct. Any mistake could result in “short rounds,” artillery shells that dropped on us instead of NVA or VC.

Toward dusk, having marched miles through dense jungle, we would set up a night perimeter. Once settled down, either myself or the sergeant’s RTO would accompany the squad setting up the automatic ambush, usually a hundred meters from where we were. We stayed in radio contact with the company, and announced our return once the AA was in place. This ensured that we would not be mistaken for the enemy. Then it was time to encode our position. I would say, “This is 2-6 India. Our November Delta Papa is Oscar Hotel Quebec, etc.”

During the night, I would initiate sitreps to confirm that the men on guard duty in foxholes around the perimeter were awake and monitoring the radio. Softly, I would speak into the handset, “This is Silverspartan 2/6 Indy. What is your sitrep?” “My sitreps are negative at this time,” was the usual reply. If it was anything else, for example, “I have movement,” the platoon leader immediately spoke with that man. If absolute silence was required, my request would be, “If your sitrep is negative, break squelch twice.” Pressing twice on the transmit button of the radio handset made a double ‘squelch’ noise on the receiving end. Simple, effective, silent.

During an ambush, firefight or mortar attack, things changed. The platoon leader would talk rapidly with the company commander, artillery units, and helicopter gunship pilots. Most, if not all radio commo would be “in the open.” There was simply no time to encrypt anything.

On April 23, 1970 I was on guard duty on LZ Francis, a fire base in Tay Ninh province. I was at a fighting position on the base perimeter. The radio was propped up against sandbags, as it had been all night with the changing guards. Around 4 AM mortars began whistling down on the base. The first shell landed 50 meters directly in front of me. I shouted “Incoming!” grabbed the radio, and started running to for cover. A mortar shell exploded, and I was hit with shrapnel, concussed, and came to face down in the dirt. I crawled to the bunker, pushing the radio ahead of me. My lieutenant and other men pulled me inside. Using coordinates that I gave to him, he directed outgoing artillery fire toward the source of the incoming shells, which eventually stopped.

I was severely wounded. Two men carried me to the aid station, where I saw Doc Levy with a casualty he’d brought in. I called to Doc, then passed out. I was medevaced to Saigon. Nine months passed before my physical wounds healed and I could walk without a cane.

I was severely wounded. Two men carried me to the aid station, where I saw Doc Levy with a casualty he’d brought in. I called to Doc, then passed out. I was medevaced to Saigon. Nine months passed before my physical wounds healed and I could walk without a cane.

Looking back, I liked being an RTO, and fully accepted the job and the faith others placed in me to do it right. I’m happy to report my sit reps are negative at this time.

_________________________

Wikipedia on 2600. Jeff Motyka’s article as it appears in 2600.

Romeo Tango Oscar

Delta 1/7 Cav grunt Jeff Motyka spent many months in hospital after being severely wounded on LZ Francis. Here, he describes his days and nights in Vietnam. First published in 2600, The Hacker Quarterly,Vol 32, Number 4, 2016.

The US Army sent me to Viet Nam in 1969. I served as a combat infantryman, a rifleman, assigned to the Second Platoon of Company D, 1st Battalion, Seventh Cavalry, First Cavalry Division. During my first two months I was just another grunt humping the boonies. I had always been detail-oriented, and drew the diagrams when we set up automatic ambushes.

An AA consisted of several claymore mines linked by det cord; they exploded when a simple tripwire device was touched. My job was to record where each Claymore was placed and where the tripwire and the blasting caps and ignition flare were located. My sketch would be used the next morning to locate and safely disable the mines. This attention to detail put me in line to become the next radio telephone operator (RTO for short) when that man was either wounded, killed, or completed his tour and went home.

In an infantry platoon of twenty men, there is a platoon leader, usually a lieutenant, and a platoon sergeant. Each has an RTO assigned exclusively to him for commo. The radios the RTO’s carry are the lifeline to other platoons, the company commander, medevacs, artillery support, gunships, and resupply. There is no formal training other than observing an radio operator for a day or two. The rest is learned on the job.

In late February 1970 Delta company was on LZ Compton, a remote fire base in Song Be province, when the NVA launched a ferocious mortar attack. The platoon command bunker took a direct hit. One man was killed and six were wounded. Among the dead and wounded was the acting platoon leader, the new platoon sergeant, and both their RTO’s.

Song Be province, when the NVA launched a ferocious mortar attack. The platoon command bunker took a direct hit. One man was killed and six were wounded. Among the dead and wounded was the acting platoon leader, the new platoon sergeant, and both their RTO’s.

The next day our new platoon leader, a fresh faced 2nd lieutenant, arrived, and I became his RTO. The first thing I had to learn was the Army/NATO phonetic alphabet, where each letter is represented by a specific word. A/Alpha, B/Bravo, C/Charlie, and so on. Words are used instead of letters to avoid confusion with letters that sound alike.

The next task was to learn the specific identifiers for the company. The company commander was “6”. Each platoon leader was designated by the platoon number and then 6. The first platoon leader was 1-6, the second platoon leader was 2-6. Each platoon sergeant was “5”. So, the second platoon sergeant was 2-5, and so on. Each RTO was designated as “India”. So, the company commander’s RTO was 6-India. As the 2nd platoon leader’s radio man, I was 2-6-India. Our platoon sergeant’s RTO was 2-5-India. This may sound confusing, but it was logical, made sense, and learned quickly.

The PRC-25 was water resistant. I never totally submerged it—I don’t know if it would still operate after being waterlogged, but we RTOs did our best to keep it dry when crossing rivers or streams. The hand set was thought to be easily damaged by water. When it rained, we wrapped it in plastic, which didn’t interfere with commo. I could walk through most jungle conditions with no problems. On occasion, we used a folding antenna, about ten feet long, which increased the frequency strength, but it was so tall and rigid it could only be used when we settled in place. Considering everything I encountered, I felt confident with the radio. I never experienced a situation when the PRC-25 did not work. The radio took on water, dust, dirt, heat, bumps, bangs, and drops, and never failed.

Regulations required changing the battery daily. Weighing three pounds, and three to four inches thick, the oblong blocks clicked into place in a protective compartment which shielded them from wind and rain. Once the new battery was installed, the old battery was destroyed. In relatively safe areas, we smashed the battery with a shovel or a rock, or hacked it with a machete. Otherwise, two wires in the battery were pulled out and attached together. This caused the battery to short out, rendering it useless to the enemy, who had their own booby traps.

to four inches thick, the oblong blocks clicked into place in a protective compartment which shielded them from wind and rain. Once the new battery was installed, the old battery was destroyed. In relatively safe areas, we smashed the battery with a shovel or a rock, or hacked it with a machete. Otherwise, two wires in the battery were pulled out and attached together. This caused the battery to short out, rendering it useless to the enemy, who had their own booby traps.

In the jungle, we were re-supplied by helicopters every three days or so. Each radio man received three new batteries. Immediately, we replaced the old one. The other two went into our packs. Due to the additional weight, RTO’s did not carry Claymore mines and M60 machine gun ammunition, which every man, except the medic, did.

On patrol, I walked directly behind the platoon leader, the radio strapped to my ruck, passing him the handset as needed. This allowed him to receive and transmit orders while moving forward. Whenever we stopped to set up a temporary position, the platoon leader would determine our location on his topo map and give me the latitude and longitude coordinates. Using a code book, I would convert them to letters. Since the code book had different alpha-numeric conversions for each day, and each twelve-hour portion of the day, it was critical to locate the right conversion page.

If we came under attack, I would call in our encrypted coordinates for artillery fire, confident that my codes were correct. Any mistake could result in “short rounds,” artillery shells that dropped on us instead of NVA or VC.

Toward dusk, having marched miles through dense jungle, we would set up a night perimeter. Once settled down, either myself or the sergeant’s RTO would accompany the squad setting up the automatic ambush, usually a hundred meters from where we were. We stayed in radio contact with the company, and announced our return once the AA was in place. This ensured that we would not be mistaken for the enemy. Then it was time to encode our position. I would say, “This is 2-6 India. Our November Delta Papa is Oscar Hotel Quebec, etc.”

During the night, I would initiate sitreps to confirm that the men on guard duty in foxholes around the perimeter were awake and monitoring the radio. Softly, I would speak into the handset, “This is Silverspartan 2/6 Indy. What is your sitrep?” “My sitreps are negative at this time,” was the usual reply. If it was anything else, for example, “I have movement,” the platoon leader immediately spoke with that man. If absolute silence was required, my request would be, “If your sitrep is negative, break squelch twice.” Pressing twice on the transmit button of the radio handset made a double ‘squelch’ noise on the receiving end. Simple, effective, silent.

During an ambush, firefight or mortar attack, things changed. The platoon leader would talk rapidly with the company commander, artillery units, and helicopter gunship pilots. Most, if not all radio commo would be “in the open.” There was simply no time to encrypt anything.

On April 23, 1970 I was on guard duty on LZ Francis, a fire base in Tay Ninh province. I was at a fighting position on the base perimeter. The radio was propped up against sandbags, as it had been all night with the changing guards. Around 4 AM mortars began whistling down on the base. The first shell landed 50 meters directly in front of me. I shouted “Incoming!” grabbed the radio, and started running to for cover. A mortar shell exploded, and I was hit with shrapnel, concussed, and came to face down in the dirt. I crawled to the bunker, pushing the radio ahead of me. My lieutenant and other men pulled me inside. Using coordinates that I gave to him, he directed outgoing artillery fire toward the source of the incoming shells, which eventually stopped.

Looking back, I liked being an RTO, and fully accepted the job and the faith others placed in me to do it right. I’m happy to report my sit reps are negative at this time.

_________________________

Wikipedia on 2600. Jeff Motyka’s article as it appears in 2600.