Weeks passed. Two months went by. One night, around 9:30pm, the phone rang.

“Hello,” I said.

“So, tell me. How’s Stevie doing?” a mysterious voice asked.

I had no idea who it was, or what he was talking about.

And we talked. Two hours went by. For several months, two or three times a month, Frank called, or I called him, and we talked at length—about politics, poets, writers. About things going in his life. Or what had happened to him forty years ago. Or to me in mine. Sometimes Frank read me his poems. Or played his shakuhachi—his Chinese bamboo flute. Or told remarkable stories. His abiding concern was steadfast honesty, and right action when faced with corruption.

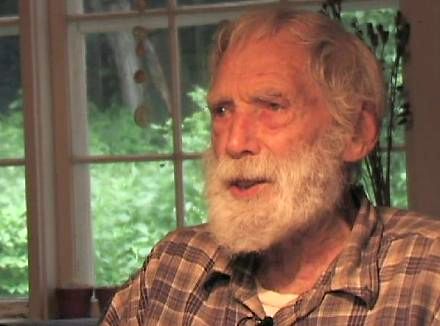

One night I mentioned Peter Kane Dufault. We had met in ’97. After travels in  Southeast Asia, where I had many adventures, but many flashbacks and crippling anxiety, I spent seven weeks in a PTSD ward in Montrose, NY. Afterward, I couch surfed—month here, a month there. A friend asked Peter and his wife if the extra room was free. Once or twice a week, for three months, I visited wry, white bearded, wise and grumpy, well-read, still handsome Peter, who lived in a shack a few hundred yards from his house in the Hudson Valley woods.

Southeast Asia, where I had many adventures, but many flashbacks and crippling anxiety, I spent seven weeks in a PTSD ward in Montrose, NY. Afterward, I couch surfed—month here, a month there. A friend asked Peter and his wife if the extra room was free. Once or twice a week, for three months, I visited wry, white bearded, wise and grumpy, well-read, still handsome Peter, who lived in a shack a few hundred yards from his house in the Hudson Valley woods.

We talked poetry, books, war, politics. Played chess. From time to time Peter played the guitar, banjo, bag pipes or fiddle. From time to time we walked the long conservancy fields or trails. Or I rode his three speed English bicycle for endless miles on the long country black top roads. To Philmont. To Chatham. To the Farm Store. Or we drove in his mud spattered jeep to a farther town, a three-foot plywood square jammed behind his “pilots back.” He’d flown bombers in WWII. The long flights had injured his spine. Peter, an accomplished and respected poet, read my war poems. Trashed all but one.

Grumpily, “Do we need this?” he asked, red lining half the page. “Or this?” Turning the page, “Take this out. Scratch that.” Until finally, “This is your voice,” he said, clenching the final sheet. “You need to write like this.”

“Are you shitting me?” said Frank. “You knew Peter? We were close friends.”

“I’m with Frank in thick dark jungle. I say, “Frank, look over there, about 20 yards away, about 20 feet up.” Behind tree branches, a kitten, with big eyes, peers at us. Nearby, a crow, or bird of prey. I turn around and say to Frank, “There’s something behind you. It’s like you have four eyes.” The skull of the beast has ocular ridges. The pupils of the eyes are small and yellow. Frank says, “Well, what do you want me to do?” I tell him, “You could move slowly, or scare it by moving fast.” Whatever it is suddenly runs away. Frank and I decide where to go next. Suddenly the gorilla rushes at me, biting my fingers, then it scampers away. Moments later the animal reappears to bite my fingers a second time. We manage to catch it and wrestle it into a large bowling ball bag. I look at my bitten fingers. Outloud I wonder if I’ll need shots. I unzipper the bag and look down at the gorilla, which sits in the dark. I yell, “Ahhhhhhhh!!” Frank says to stop yelling at the gorilla. He sets it free, or it escapes on its own, and runs through the jungle to a high dirt hill, where it lifts its head, pounds its chest, and howls.

Let Me Be Frank: Francesco Serpico, A Genuine Actor

by Edward Curtin

“There are unconscious actors among them and involuntary actors; the genuine are always rare, especially genuine actors.”

– Friedrick Nietzche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra

“Any artist [person] who goes in for being famous in our society must know that it is not he who will become famous, but someone else under his name, someone who will eventually escape him and perhaps someday will kill the true artist [person] in him.”

– Albert Camus, “Create Dangerously”

“It ain’t me you’re lookin for, babe.”

– Bob Dylan, It Ain’t Me, Babe

Enter

The set was real but illusionary: A legendary old New England hotel dressed festively for Christmas and the holiday season. Norman Rockwell’s magical realism. The lobby full with merriment, the cozy fire dancing to the sweet sound of violin and piano Christmas music mixed with a subtle alcoholic fragrance. Main Street U.S.A. Snow on the street and the classic strains of “White Christmas” in the inner air. A mythic setting for meeting a legendary actor.

But as I entered the dimly lit set, the legend was nowhere to be seen. I approached the spot where the musicians were playing and didn’t see him in the room opposite. Then, as I was greeting two actors with bit parts that I knew (unconscious actors, I should add), out of the shadows came a laughing Russian spy obviously dressed as a Russian spy, one red star on his hat, walking stick in hand. He and I were there to have a drink and enjoy the music that would allow us to talk privately without being overheard. A few hours earlier he had sent me a strange message from Epicurus: “It is impossible to lead a pleasant life without living wisely and well and justly, and it is impossible to live wisely and well and justly without living pleasantly (‘justly’ meaning to prevent a person from harming or being harmed by another).”

What did this cryptic message mean? The day before I had met a leading expert on the CIA on the same set and we had discussed the criminal activities of the Agency, how they dissembled and lied in their self-declared mission to defeat communism everywhere, even where it didn’t exist. Those people were great at creating false myths, counter-myths, and Hollywood/media narratives to discombobulate a public already lost in an entertainment culture. Now I was meeting this crazy Russian whom I heard say to some passing actors that he was a communist, and then he said something in Latin that totally perplexed them, which made him laugh. A woman approached him and said she liked his hat. Again he replied in Latin with a Russian accent and her face dropped. Then we all laughed. She blushed, the scent of flirtation in the badinage. Was this guy serious or a comic having fun?

Off to the bar he and I went for some vino, wisecracks spewing from the mad Russian’s mouth. Heads turned to watch our passage, for even on this movie set, his costume stood out.

The True Man

As we settled in a corner with our drinks, a joyous warmth enveloped us. Play-acting was fun. Francesco was good at it. Here in the Red Lion Inn in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, no one took him for the legendary New York City Detective, Frank Serpico, shot in the face for being a whistleblower before the word became commonplace, and made mythic through the 1973 movie, Serpico. To the people surrounding us, he was just an amusing guy in an interesting hat, a man having fun with a buddy.

At a round table in front of the chairs we were sitting in, a group of six middle-aged adults sat playing cards. They were not conversing. Frank mentioned that they reminded him of those pictures of dogs playing cards. He got up and asked them if they were playing for high stakes. They laughingly said no, just for amusement. And what game were they playing? I asked. A children’s game, the woman said. It was a perfect scene from a spoof, and Frank whispered to me, “The masses are deluded with TV, Hollywood, and children’s games. Let’s bark.”

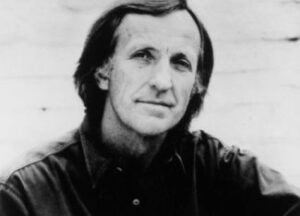

“Become who you are,” advised Nietzsche. Frank had done that; had always done it, despite decades of having to escape the mythic masked man Hollywood had made of him when Al Pacino played him in 1973, creating the legendary persona behind which the real person is expected to disappear, held hostage by the mask. While all persons are, by definition, masked, the word person being derived from the Latin, persona, meaning mask, there are those who are nothing but masks – hollow inside. Empty. No one home. Unconscious and involuntary actors living out a script written by someone else. Not Frank Serpico. He has consistently been an unmasker, a truth-teller exposing the fraud that is so endemic in this society of illusions and delusions where lying is the norm.

The Lone Ranger

Frank has always understood masks. When he was an undercover cop, he used his play acting skills to save his life. In the recent documentary film, “Frank Serpico,” directed by Antonino D’Ambrosio, he says he told himself: “You’re going on the stage tonight. The audience is out there. I told myself I was an actor and I had to sell my role. I got my training in the streets of New York where I played many roles from a doctor to a derelict and how well I played those roles my life depended on it.” His acting skills were his protection, but these acts were performed in the service of protecting the citizens he had vowed to protect. Genuine acts.

Shakespeare was right, of course, “all the world’s a stage,” though I would disagree with the bard that we are “merely” players. It does often seem that way, but seeming is the essence of the actor’s show and tell. But who are we behind the masks? Who is it uttering those words coming through the masks’ mouth holes (the per-sona, Latin, to sound through). In Frank’s case, the real man is not hard to find. Never was. From a young age he was incorruptible. When he became a cop and took his oath, he was the same honest guy, though not fully aware of the dishonesty that pervades society at all levels.

When this honest cop was lying in a pool of his own blood on the night of February 3, 1971, having been shot in the face in a set-up carried out by fellow cops, Frank Serpico heard a voice that said, “It’s all a lie.” In that moment as he fought for his life, he realized a truth he had previously sensed but never fully grasped in its awful reality. His honesty, his refusal to be a corrupt cop like so many others, his allegiance to the sacred oath he took when he became a police officer, was returned with a violent snarl by the liars he walked among. And in that moment he was determined to live and return their lies with more truth, which he did in his subsequent eloquent testimony to the Knapp Commission that was investigating police corruption in the New York Police Department because of him.

The After Life

But then came the rest of his life, not a small thing. Lionized and damned as a “rat” by many cops, recreated through the superb actor’s mask of Al Pacino in the film Serpico, his legend was created by the celebrity machine. His truth was turned into a Hollywood myth; a true American hero became a cool movie star. But unlike a movie actor or entertainer, he was still Frankie the honest boy who became an honest cop, and he wanted to become who he was, not an actor playing someone else.

Police work was his “calling,” he told me. It is a word with deep religious roots. A vocation (Latin, vocare, to call). The mythographer Joseph Campbell has written eloquently of “the call” in The Hero with a Thousand Faces. When one is called by this mysterious voice that many call God, this call to adventure and authenticity – the hero’s way, he terms it – one is faced with a choice whether to accept or refuse. Campbell writes:

“[It] signifies that destiny has summoned the hero and transferred his spiritual center of gravity from within the pale of his society to a zone unknown. This fateful region of both treasure and danger may be variously represented: as a distant land, a forest, a kingdom underground, beneath the waves, or above the sky, a secret island, lofty mountaintop, or profound dream state; but it is always a place of strangely fluid and polymorphous beings, unimaginable torments, superhuman deeds, and impossible delight.”

From the start of his police work, Frank sensed he was moving in “a zone unknown” and danger lurked along the way, but he had accepted the call. Like the heroes in all the authentic myths, he could not be sure where it was all leading. He came to realize that it led to the depths of hell, the frightening underworld through which the hero must transit or perish. The dark night of the soul. A near death experience at the hands of the monsters. Unimaginable torments.

Across the Wine-Dark Sea

But dawn broke slowly, the same rosy-fingered dawn that greeted Odysseus as he contemplated the next step on his journey “home” from the war zone. So Frank left home, set sail for Europe, and although a wounded warrior, he took up the rest of his life. “Some may say I’m full of it,” he said to me, “but my life has been like a serendipitous dream, one scene after another.” This may surprise those who think of him only as Frank Serpico, the heroic and honest cop. But that was a role he played, something he did, not who he was. He has led a colorful, exciting, and adventurous life, but not because of the movie and book about his cop’s life. His name Frank, after all, means a free man, and Frank is the epitome of a free-spirited soul, always trying to escape others’ definitions of him. Sitting with our wine amid the music, he said:

I wanted to be who I was before the shooting. Back then I knew more people and they knew me. Friends. Afterwards they made me into their own image. They were looking for perfection, but I wasn’t perfect. So I became more guarded and felt I was living under a microscope. Even among friends, if we were playing a game in which you could make up things, like a word game, and pretend just for fun, and I did it like them, they would look at me as if I couldn’t, that if I did, I was betraying myself as the honest cop. I had become the legendary honest cop to them, not Frank, a guy who had lived up to his oath to be an honest cop, but who was also a regular person, not a celebrity. So I’ve had to deal with people being drawn to me because they think I’m a celebrity. I’m not an actor. I’m the real thing.

I was drawn to him because I sensed he was a compañero, similar to old, authentic friends I had grown up with in the Bronx. Guys with consciences, not crooks. Friends who could laugh and joke around. From our first meeting we connected: each of us dressed in individual camouflage – he, the bearded, aging Village hippie, concealing a conscience-stricken Italian-American kid from Brooklyn; me, sporting the look of an Irish-American something from the Bronx, concealing a conscience-stricken radical thinker and writer. Birds of a feather under different plumage, costumes concealing our true identities. Real play acting.

And then there was that Catholic thing. Both of us products of New York Catholic families and schools. Thus conscience does not necessarily make cowards of us all. It also calls to us be honest, brave, and frank, despite the corruption of religious institutions. Nietzsche again: “‘Christianity’ has become something fundamentally different from what its founder did and desired….What did Christ deny? Everything that is today called Christian.” Frank hated school, and when he attended St. Francis Prep he was beaten by a religious Brother. Then, when this teacher died and was being waked, Frank looked at him in the coffin and found himself, to his own amazement, crying for the man. “That’s how deep it goes into you,” he said to me, “you end up crying for your tormentor.” And while I understood his point of criticism that a corrupt society reaches into the cradle to poison us from the start, I thought there was more to it, some deep human empathy in that boy’s soul. In the man’s. Like Nietzsche, I sense in Frank a Romantic at heart. He once wrote a poem in which he said:

I was taught religion and all about race

I was taught so well I felt out of place

But now I am a man and have no one to blame

So I must forget words like guilty, stupid, and shame.

And with the help of my soul I’ll remember the way

And get back where I was on that very first day.

Then he added in prose: “The God I believe in is not just my God, but the God of all beings no matter what language they speak….I have no use for man-made religion….They profane the name of Christ but none follow in his footsteps save a few perhaps like St Francis and even Vincent Van Gogh.”

The few: St. Francis and Van Gogh. Telling choices. The wounded artist with a primal sympathy for the poor and the saint who drew animals to him out of love for all beings. St. Francis Prep where Frank was first wounded by a sadist, a sign of things to come. And later, the lover of nature who lives in the country and feeds birds that eat out of his hands. The man who has written a beautiful essay about Henry David Thoreau. And the artist/genuine actor who writes, plays musical instruments, has acted in theatre, is producing a film about former Attorney General Ramsey Clark, another maverick who has also come in for severe criticism.

The Lying Rats

“What has been your reaction over the years to having been harshly criticized as a “rat” by so many N.Y. cops?” I asked him.

“I took it as a joke,” he said. “I am a rat. It’s my Chinese zodiac sign.” But turning more serious, he added, “I never broke bread with these people, so I never could rat on them. I was never a part of them.

In fact, when I was asked to wear a wire to record guys I worked with, I said absolutely not. I wasn’t out to catch individuals, but to warn of corruption throughout the system, from bottom to top in the Police Department. It’s the system I wanted to change, so in no way was I ever a rat.”

“What sustained you all these years? Was it faith, love, family – what?”

”It was wine, women, and song,” he replied with a smile, as he held up his glass for a toast.

As we were walking through the crowded lobby, a woman was rocking in a rocking chair. Frank burst into song about a rocking chair to amuse me; then told me he was once sitting outside a café and someone approached him to act in a production of William Saroyan’s The Time of Your Life. He said to the guy, “But I’m not an actor.” “But you look the part of the Arab in the play,” was the reply. So he took the part of the unnamed Arab and got to recite the most famous lines: “No foundation all the way down the line. No foundation all the way down the line.” A refrain that echoes Frank’s take on American society today. “It’s all a lie” or “No foundation all the way down the line” – little difference.

Until we see through the charade of social life and realize the masked performers are not just the politicians and celebrities, not only the professional actors and the corporate media performers, but us, we won’t grasp the problem. Lying is the leading cause of living death in the United States. We live in a society built of lies; lying and dishonesty are the norm. They are built into the fabric of all our institutions.

Later he quoted for me the preface to that play, words dear to his heart:

“In the time of your life, live – so that in that good time there shall be no ugliness or death for yourself or any life your life touches. Seek goodness everywhere, and when it is found, bring it out of its hiding place and let it be free and unashamed. Place in matter and flesh the least of the values, for these are the things that hold death and must pass away. Discover in all things that which shines and is beyond corruption. Encourage virtue in whatever heart it may have been driven into secrecy and sorrow by the shame and terror of the world. Ignore the obvious, for it is unworthy of the clear eye and kindly heart. Be the inferior of no man, or of any man be superior.Remember that every man is a variation of yourself. No man’s guilt is not yours, nor is any man’s innocence a thing apart. Despise evil and ungodliness, but not men of ungodliness or evil. These, understand. Have no shame in being kindly and gentle but if the time comes in the time of your life to kill, kill and have no regret. In the time of your life, live – so that in the wondrous time you shall not add to the misery and sorrow of the world, but shall smile to the infinite delight and mystery of it.”

A Genuine Actor

And so I came to understand those words of Epicurus that this Thoreau-like bon-vivant had sent me. A pleasant life must be a just life, and if one is wise, and if one prevents people from harming or being harmed by others, one has chosen wisely and well. That is the way of the genuine actor. As Nietzsche meant it, a genuine actor is an original, one whose entire life is a work of art in which one begets oneself, or becomes who one is, as the Latin root of genuine (gignere, to give birth, to beget) implies. In a world of phony actors, Frank Serpico the real man, stands out.

He stood out long ago when he so courageously came forward to light a lamp of truth on the systemic corruption within the NYPD, and despite paying a severe price in suffering that almost cost him his life, he continues to speak out. Having spent a decade in exile in Europe where he entered into deep self-reflection (“There’s nothing outside that isn’t inside,” he says), he returned “home” still passionately committed to shining a light on all that is evil but taken for normality that harms people physically and spiritually.

To this day his conscience gives him no rest. He is still fighting by lending his name and presence to cases of police corruption, injustice, racism, the silencing of dissidents, etc. He does not live in the past. A while ago he protested with some NYC cops the deplorable treatment of the football player Colin Kaepernick by the National Football League. Just recently he spoke out for justice in the egregious 2004 police fatal shooting of Michael Bell, Jr. in the family driveway in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Supporting a video being distributed to 10,000 registered voters in a quest to get a public inquest, Frank wrote:

“This video equals the cell phone footage that captured the shooting of Walter Scott in South Carolina. Such compelling and condemning evidence of a cover-up and abuse can no longer be ignored. For the sake of justice in American policing, Attorney General Brad Schimel and DA Michael Graveley must reopen this investigation if society’s trust in their police is ever to be restored.”

But before anyone gets caught up in hero worship of the genuine hero that Frank is (not a pseudo-hero deceptively created by the celebrity and propaganda apparatus), his parting words are worth remembering. In this corrupt society, you had best not get ensnared in mythic fantasies about heroes coming to the rescue. It ain’t him, babe, it ain’t him you’re looking for.

When you see injustice and corruption, when you open your eyes and see lying and deceit everywhere, you must be your own hero; you must be courageous and act. “Take care of it yourself,” he says.

Or in the words of Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, a book that serendipitously fell into his hands when he was alone in a friend’s humble chalet in the Swiss Alps and shocked him with its relevance to his own experience: “‘This is my way, where is yours?’ thus I answered those who asked me ‘the way.’ For the way, that does not exist.”

____________________

On Being Frank

In early 2017 I mailed a hard copy query to a man in upstate New York:

“Recently I published How Stevie Nearly Lost the War and Other Postwar Stories. The connecting theme is war and its aftermath. I think we both know a little about PTSD. Would you consider writing a blurb? I look forward to hearing from you.”

Weeks passed. Two months went by. One night, around 9:30pm, the phone rang.

“Hello,” I said.

“So, tell me. How’s Stevie doing?” a mysterious voice asked.

I had no idea who it was, or what he was talking about.

“Who is this?”

“It’s Frank.”

“Frank who?”

And we talked. Two hours went by. For several months, two or three times a month, Frank called, or I called him, and we talked at length—about politics, poets, writers. About things going in his life. Or what had happened to him forty years ago. Or to me in mine. Sometimes Frank read me his poems. Or played his shakuhachi—his Chinese bamboo flute. Or told remarkable stories. His abiding concern was steadfast honesty, and right action when faced with corruption.

One night I mentioned Peter Kane Dufault. We had met in ’97. After travels in Southeast Asia, where I had many adventures, but many flashbacks and crippling anxiety, I spent seven weeks in a PTSD ward in Montrose, NY. Afterward, I couch surfed—month here, a month there. A friend asked Peter and his wife if the extra room was free. Once or twice a week, for three months, I visited wry, white bearded, wise and grumpy, well-read, still handsome Peter, who lived in a shack a few hundred yards from his house in the Hudson Valley woods.

Southeast Asia, where I had many adventures, but many flashbacks and crippling anxiety, I spent seven weeks in a PTSD ward in Montrose, NY. Afterward, I couch surfed—month here, a month there. A friend asked Peter and his wife if the extra room was free. Once or twice a week, for three months, I visited wry, white bearded, wise and grumpy, well-read, still handsome Peter, who lived in a shack a few hundred yards from his house in the Hudson Valley woods.

We talked poetry, books, war, politics. Played chess. From time to time Peter played the guitar, banjo, bag pipes or fiddle. From time to time we walked the long conservancy fields or trails. Or I rode his three speed English bicycle for endless miles on the long country black top roads. To Philmont. To Chatham. To the Farm Store. Or we drove in his mud spattered jeep to a farther town, a three-foot plywood square jammed behind his “pilots back.” He’d flown bombers in WWII. The long flights had injured his spine. Peter, an accomplished and respected poet, read my war poems. Trashed all but one.

Grumpily, “Do we need this?” he asked, red lining half the page. “Or this?” Turning the page, “Take this out. Scratch that.” Until finally, “This is your voice,” he said, clenching the final sheet. “You need to write like this.”

“Are you shitting me?” said Frank. “You knew Peter? We were close friends.”

In the department of small world, that’s as good as it gets.*

The other day I had this dream:

“I’m with Frank in thick dark jungle. I say, “Frank, look over there, about 20 yards away, about 20 feet up.” Behind tree branches, a kitten, with big eyes, peers at us. Nearby, a crow, or bird of prey. I turn around and say to Frank, “There’s something behind you. It’s like you have four eyes.” The skull of the beast has ocular ridges. The pupils of the eyes are small and yellow. Frank says, “Well, what do you want me to do?” I tell him, “You could move slowly, or scare it by moving fast.” Whatever it is suddenly runs away. Frank and I decide where to go next. Suddenly the gorilla rushes at me, biting my fingers, then it scampers away. Moments later the animal reappears to bite my fingers a second time. We manage to catch it and wrestle it into a large bowling ball bag. I look at my bitten fingers. Outloud I wonder if I’ll need shots. I unzipper the bag and look down at the gorilla, which sits in the dark. I yell, “Ahhhhhhhh!!” Frank says to stop yelling at the gorilla. He sets it free, or it escapes on its own, and runs through the jungle to a high dirt hill, where it lifts its head, pounds its chest, and howls.

The next day, on CounterPunch, I came across this portrait of Frank:

Let Me Be Frank: Francesco Serpico, A Genuine Actor

by Edward Curtin

“There are unconscious actors among them and involuntary actors; the genuine are always rare, especially genuine actors.”

– Friedrick Nietzche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra

“Any artist [person] who goes in for being famous in our society must know that it is not he who will become famous, but someone else under his name, someone who will eventually escape him and perhaps someday will kill the true artist [person] in him.”

– Albert Camus, “Create Dangerously”

“It ain’t me you’re lookin for, babe.”

– Bob Dylan, It Ain’t Me, Babe

Enter

The set was real but illusionary: A legendary old New England hotel dressed festively for Christmas and the holiday season. Norman Rockwell’s magical realism. The lobby full with merriment, the cozy fire dancing to the sweet sound of violin and piano Christmas music mixed with a subtle alcoholic fragrance. Main Street U.S.A. Snow on the street and the classic strains of “White Christmas” in the inner air. A mythic setting for meeting a legendary actor.

But as I entered the dimly lit set, the legend was nowhere to be seen. I approached the spot where the musicians were playing and didn’t see him in the room opposite. Then, as I was greeting two actors with bit parts that I knew (unconscious actors, I should add), out of the shadows came a laughing Russian spy obviously dressed as a Russian spy, one red star on his hat, walking stick in hand. He and I were there to have a drink and enjoy the music that would allow us to talk privately without being overheard. A few hours earlier he had sent me a strange message from Epicurus: “It is impossible to lead a pleasant life without living wisely and well and justly, and it is impossible to live wisely and well and justly without living pleasantly (‘justly’ meaning to prevent a person from harming or being harmed by another).”

What did this cryptic message mean? The day before I had met a leading expert on the CIA on the same set and we had discussed the criminal activities of the Agency, how they dissembled and lied in their self-declared mission to defeat communism everywhere, even where it didn’t exist. Those people were great at creating false myths, counter-myths, and Hollywood/media narratives to discombobulate a public already lost in an entertainment culture. Now I was meeting this crazy Russian whom I heard say to some passing actors that he was a communist, and then he said something in Latin that totally perplexed them, which made him laugh. A woman approached him and said she liked his hat. Again he replied in Latin with a Russian accent and her face dropped. Then we all laughed. She blushed, the scent of flirtation in the badinage. Was this guy serious or a comic having fun?

Off to the bar he and I went for some vino, wisecracks spewing from the mad Russian’s mouth. Heads turned to watch our passage, for even on this movie set, his costume stood out.

The True Man

As we settled in a corner with our drinks, a joyous warmth enveloped us. Play-acting was fun. Francesco was good at it. Here in the Red Lion Inn in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, no one took him for the legendary New York City Detective, Frank Serpico, shot in the face for being a whistleblower before the word became commonplace, and made mythic through the 1973 movie, Serpico. To the people surrounding us, he was just an amusing guy in an interesting hat, a man having fun with a buddy.

At a round table in front of the chairs we were sitting in, a group of six middle-aged adults sat playing cards. They were not conversing. Frank mentioned that they reminded him of those pictures of dogs playing cards. He got up and asked them if they were playing for high stakes. They laughingly said no, just for amusement. And what game were they playing? I asked. A children’s game, the woman said. It was a perfect scene from a spoof, and Frank whispered to me, “The masses are deluded with TV, Hollywood, and children’s games. Let’s bark.”

“Become who you are,” advised Nietzsche. Frank had done that; had always done it, despite decades of having to escape the mythic masked man Hollywood had made of him when Al Pacino played him in 1973, creating the legendary persona behind which the real person is expected to disappear, held hostage by the mask. While all persons are, by definition, masked, the word person being derived from the Latin, persona, meaning mask, there are those who are nothing but masks – hollow inside. Empty. No one home. Unconscious and involuntary actors living out a script written by someone else. Not Frank Serpico. He has consistently been an unmasker, a truth-teller exposing the fraud that is so endemic in this society of illusions and delusions where lying is the norm.

The Lone Ranger

Frank has always understood masks. When he was an undercover cop, he used his play acting skills to save his life. In the recent documentary film, “Frank Serpico,” directed by Antonino D’Ambrosio, he says he told himself: “You’re going on the stage tonight. The audience is out there. I told myself I was an actor and I had to sell my role. I got my training in the streets of New York where I played many roles from a doctor to a derelict and how well I played those roles my life depended on it.” His acting skills were his protection, but these acts were performed in the service of protecting the citizens he had vowed to protect. Genuine acts.

Shakespeare was right, of course, “all the world’s a stage,” though I would disagree with the bard that we are “merely” players. It does often seem that way, but seeming is the essence of the actor’s show and tell. But who are we behind the masks? Who is it uttering those words coming through the masks’ mouth holes (the per-sona, Latin, to sound through). In Frank’s case, the real man is not hard to find. Never was. From a young age he was incorruptible. When he became a cop and took his oath, he was the same honest guy, though not fully aware of the dishonesty that pervades society at all levels.

When this honest cop was lying in a pool of his own blood on the night of February 3, 1971, having been shot in the face in a set-up carried out by fellow cops, Frank Serpico heard a voice that said, “It’s all a lie.” In that moment as he fought for his life, he realized a truth he had previously sensed but never fully grasped in its awful reality. His honesty, his refusal to be a corrupt cop like so many others, his allegiance to the sacred oath he took when he became a police officer, was returned with a violent snarl by the liars he walked among. And in that moment he was determined to live and return their lies with more truth, which he did in his subsequent eloquent testimony to the Knapp Commission that was investigating police corruption in the New York Police Department because of him.

The After Life

But then came the rest of his life, not a small thing. Lionized and damned as a “rat” by many cops, recreated through the superb actor’s mask of Al Pacino in the film Serpico, his legend was created by the celebrity machine. His truth was turned into a Hollywood myth; a true American hero became a cool movie star. But unlike a movie actor or entertainer, he was still Frankie the honest boy who became an honest cop, and he wanted to become who he was, not an actor playing someone else.

Police work was his “calling,” he told me. It is a word with deep religious roots. A vocation (Latin, vocare, to call). The mythographer Joseph Campbell has written eloquently of “the call” in The Hero with a Thousand Faces. When one is called by this mysterious voice that many call God, this call to adventure and authenticity – the hero’s way, he terms it – one is faced with a choice whether to accept or refuse. Campbell writes:

From the start of his police work, Frank sensed he was moving in “a zone unknown” and danger lurked along the way, but he had accepted the call. Like the heroes in all the authentic myths, he could not be sure where it was all leading. He came to realize that it led to the depths of hell, the frightening underworld through which the hero must transit or perish. The dark night of the soul. A near death experience at the hands of the monsters. Unimaginable torments.

Across the Wine-Dark Sea

But dawn broke slowly, the same rosy-fingered dawn that greeted Odysseus as he contemplated the next step on his journey “home” from the war zone. So Frank left home, set sail for Europe, and although a wounded warrior, he took up the rest of his life. “Some may say I’m full of it,” he said to me, “but my life has been like a serendipitous dream, one scene after another.” This may surprise those who think of him only as Frank Serpico, the heroic and honest cop. But that was a role he played, something he did, not who he was. He has led a colorful, exciting, and adventurous life, but not because of the movie and book about his cop’s life. His name Frank, after all, means a free man, and Frank is the epitome of a free-spirited soul, always trying to escape others’ definitions of him. Sitting with our wine amid the music, he said:

I was drawn to him because I sensed he was a compañero, similar to old, authentic friends I had grown up with in the Bronx. Guys with consciences, not crooks. Friends who could laugh and joke around. From our first meeting we connected: each of us dressed in individual camouflage – he, the bearded, aging Village hippie, concealing a conscience-stricken Italian-American kid from Brooklyn; me, sporting the look of an Irish-American something from the Bronx, concealing a conscience-stricken radical thinker and writer. Birds of a feather under different plumage, costumes concealing our true identities. Real play acting.

And then there was that Catholic thing. Both of us products of New York Catholic families and schools. Thus conscience does not necessarily make cowards of us all. It also calls to us be honest, brave, and frank, despite the corruption of religious institutions. Nietzsche again: “‘Christianity’ has become something fundamentally different from what its founder did and desired….What did Christ deny? Everything that is today called Christian.” Frank hated school, and when he attended St. Francis Prep he was beaten by a religious Brother. Then, when this teacher died and was being waked, Frank looked at him in the coffin and found himself, to his own amazement, crying for the man. “That’s how deep it goes into you,” he said to me, “you end up crying for your tormentor.” And while I understood his point of criticism that a corrupt society reaches into the cradle to poison us from the start, I thought there was more to it, some deep human empathy in that boy’s soul. In the man’s. Like Nietzsche, I sense in Frank a Romantic at heart. He once wrote a poem in which he said:

Then he added in prose: “The God I believe in is not just my God, but the God of all beings no matter what language they speak….I have no use for man-made religion….They profane the name of Christ but none follow in his footsteps save a few perhaps like St Francis and even Vincent Van Gogh.”

The few: St. Francis and Van Gogh. Telling choices. The wounded artist with a primal sympathy for the poor and the saint who drew animals to him out of love for all beings. St. Francis Prep where Frank was first wounded by a sadist, a sign of things to come. And later, the lover of nature who lives in the country and feeds birds that eat out of his hands. The man who has written a beautiful essay about Henry David Thoreau. And the artist/genuine actor who writes, plays musical instruments, has acted in theatre, is producing a film about former Attorney General Ramsey Clark, another maverick who has also come in for severe criticism.

The Lying Rats

“What has been your reaction over the years to having been harshly criticized as a “rat” by so many N.Y. cops?” I asked him.

“I took it as a joke,” he said. “I am a rat. It’s my Chinese zodiac sign.” But turning more serious, he added, “I never broke bread with these people, so I never could rat on them. I was never a part of them.

In fact, when I was asked to wear a wire to record guys I worked with, I said absolutely not. I wasn’t out to catch individuals, but to warn of corruption throughout the system, from bottom to top in the Police Department. It’s the system I wanted to change, so in no way was I ever a rat.”

“What sustained you all these years? Was it faith, love, family – what?”

”It was wine, women, and song,” he replied with a smile, as he held up his glass for a toast.

As we were walking through the crowded lobby, a woman was rocking in a rocking chair. Frank burst into song about a rocking chair to amuse me; then told me he was once sitting outside a café and someone approached him to act in a production of William Saroyan’s The Time of Your Life. He said to the guy, “But I’m not an actor.” “But you look the part of the Arab in the play,” was the reply. So he took the part of the unnamed Arab and got to recite the most famous lines: “No foundation all the way down the line. No foundation all the way down the line.” A refrain that echoes Frank’s take on American society today. “It’s all a lie” or “No foundation all the way down the line” – little difference.

Until we see through the charade of social life and realize the masked performers are not just the politicians and celebrities, not only the professional actors and the corporate media performers, but us, we won’t grasp the problem. Lying is the leading cause of living death in the United States. We live in a society built of lies; lying and dishonesty are the norm. They are built into the fabric of all our institutions.

Later he quoted for me the preface to that play, words dear to his heart:

A Genuine Actor

And so I came to understand those words of Epicurus that this Thoreau-like bon-vivant had sent me. A pleasant life must be a just life, and if one is wise, and if one prevents people from harming or being harmed by others, one has chosen wisely and well. That is the way of the genuine actor. As Nietzsche meant it, a genuine actor is an original, one whose entire life is a work of art in which one begets oneself, or becomes who one is, as the Latin root of genuine (gignere, to give birth, to beget) implies. In a world of phony actors, Frank Serpico the real man, stands out.

He stood out long ago when he so courageously came forward to light a lamp of truth on the systemic corruption within the NYPD, and despite paying a severe price in suffering that almost cost him his life, he continues to speak out. Having spent a decade in exile in Europe where he entered into deep self-reflection (“There’s nothing outside that isn’t inside,” he says), he returned “home” still passionately committed to shining a light on all that is evil but taken for normality that harms people physically and spiritually.

To this day his conscience gives him no rest. He is still fighting by lending his name and presence to cases of police corruption, injustice, racism, the silencing of dissidents, etc. He does not live in the past. A while ago he protested with some NYC cops the deplorable treatment of the football player Colin Kaepernick by the National Football League. Just recently he spoke out for justice in the egregious 2004 police fatal shooting of Michael Bell, Jr. in the family driveway in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Supporting a video being distributed to 10,000 registered voters in a quest to get a public inquest, Frank wrote:

But before anyone gets caught up in hero worship of the genuine hero that Frank is (not a pseudo-hero deceptively created by the celebrity and propaganda apparatus), his parting words are worth remembering. In this corrupt society, you had best not get ensnared in mythic fantasies about heroes coming to the rescue. It ain’t him, babe, it ain’t him you’re looking for.

When you see injustice and corruption, when you open your eyes and see lying and deceit everywhere, you must be your own hero; you must be courageous and act. “Take care of it yourself,” he says.

Or in the words of Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, a book that serendipitously fell into his hands when he was alone in a friend’s humble chalet in the Swiss Alps and shocked him with its relevance to his own experience: “‘This is my way, where is yours?’ thus I answered those who asked me ‘the way.’ For the way, that does not exist.”

____________________

Edward Curtin is a writer whose work has appeared widely. He teaches sociology at Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts.

* Frank and I stay in touch. We plan to meet.

Peter Kane Dufault: Obituary