“You must remember what you are and what you have chosen to become, and the significance of what you are doing. There are wars and defeats and victories of the human race that are not military and that are not recorded in the annals of history. Remember that while you’re trying to decide what to do.” —John Williams, Stoner

CounterPunch readers may recall “The Curious Case of Johnny Doe”, my 2015 story about a popular local veteran who loudly claimed two tours in Vietnam and fistfuls of medals. The article all but unmasked him as fake.

For several months I set Johnny Doe aside, but the old itch–was the man real or not–returned, when I stumbled across a video of Johnny recounting his tales of valor. This was no amateur film. The lighting, angles, pans, and segues bore the hallmarks of a professional.

I complimented the filmmaker on his skill, but noted that his subject was suspect. The film maker contacted Johnny’s ardent supporter and best friend, Bruce. An excerpt from Bruce’s response is enlightening:

It is a conspiracy theory of the worst kind, something they can not prove and would not believe Johnny even when presented with the facts. By doing this secretly behind Johnny’s back it is the worst kind of gossip, gossip that can be harmful to a person’s reputation. It is like publicly calling someone a child molester, who is not. Just the accusation lingers and hurts that person’s reputation. There is clearly a mistake.

It is a conspiracy theory of the worst kind, something they can not prove and would not believe Johnny even when presented with the facts. By doing this secretly behind Johnny’s back it is the worst kind of gossip, gossip that can be harmful to a person’s reputation. It is like publicly calling someone a child molester, who is not. Just the accusation lingers and hurts that person’s reputation. There is clearly a mistake.

Months later, one cold winter night in 2016, at a cozy Quaker meetinghouse, the unexpected reared its head. As I was preparing to give a talk, Bruce stormed over to me, shook my hands, exclaimed we had to talk. For ten heated minutes, in a dimlit hallway, hidden from view, his reddening face inches from mine, he raged about my questioning Johnny, a superb soldier, a decorated hero. “How dare you!” He fumed. “How dare you!” I stood my ground, hoping he’d talk himself out. “We’re contacting Senator X,” he snarled. “We’ll get documents that will show you’re wrong!” “Good,” I countered. “I look forward to seeing them.” “Me too,” he snarled, then tried cuffing me in a headlock. I pushed him off. The confrontation ended. Rattled, my talk was second rate, the evening ruined.

Six weeks later, as I walked through a snow covered park, a shivering wind rustled the trees. I crossed a busy avenue, entered the building where Johnny and I had agreed to talk.

His small windowless office was filled by a shabby desk, a shelf of office supplies, piled clothes, a copy machine, two worn out black fabric chairs. The beige walls, save for a fading political poster, were vacant. Overhead fluorescent lights cast their harsh impersonal glow.

Johnny was friendly, welcoming. As we made small talk, he dawdled an envelope on his lap. I hoped it contained the document we had discussed by email and phone.

I reminded Johnny we’d both been combat medics in Vietnam. Shared various medals. Each of us strongly identified as Vietnam vets, spoke openly about and against war, remained troubled by it. I was not angry at him, I said. I respected him. But his peculiar war tales and numerous decorations had caught my eye. What began as curiosity had snowballed into a years long desire to know the truth. Did Johnny get his gun, or not?

We reviewed my 2015 CounterPunch article, which cited Johnny’s blazing war stories, multiple valor medals, his suspect DD 214, his archived military records, which Johnny had reluctantly authorized my friend Martin to obtain from the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in St. Louis. All led to serious doubts he’d ever served in combat. And yet, I noted, there were grey areas.

For example, Johnny knew about weaponry, areas of operation, knew how grunts talked, what we did on patrol.

“Here,” he said, brightening.”I jumped through hoops to get this.”

“Here,” he said, brightening.”I jumped through hoops to get this.”

I opened the envelope and was saddened by what I saw: an undated form letter, apparently ink jet printed, from Senator X, which thanked Johnny for his service. It cited Senator Y’s help, and cited the enclosed DD 214, retrieved from a court house in New York. A VA memo confirmed the senators’ document request.

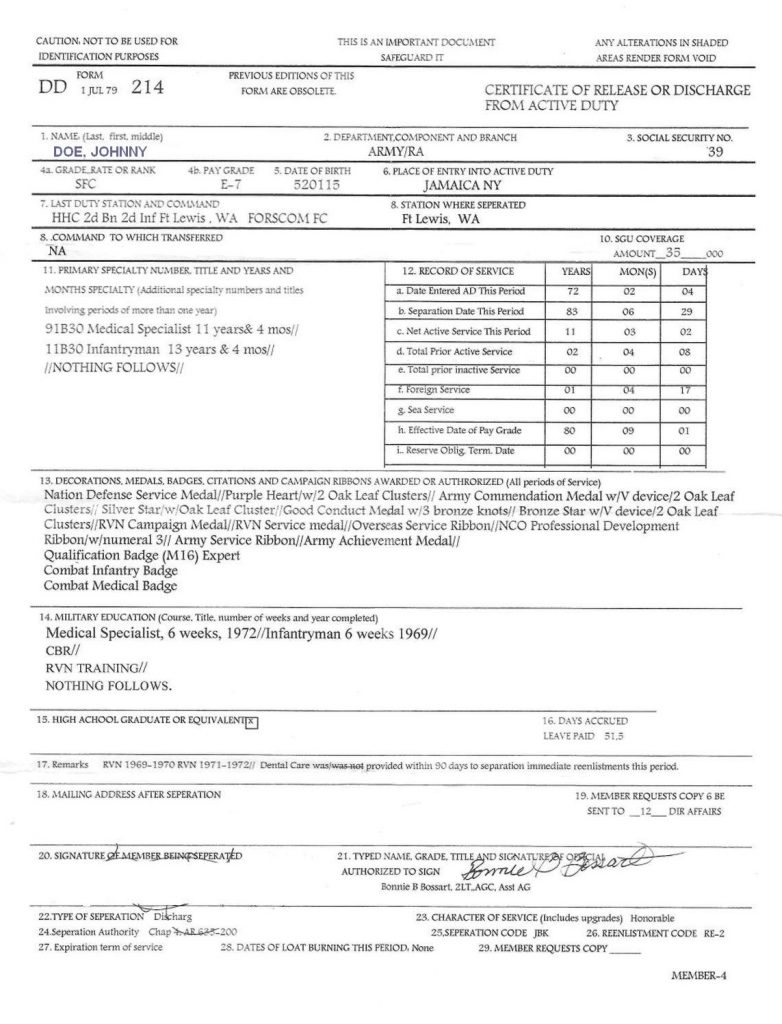

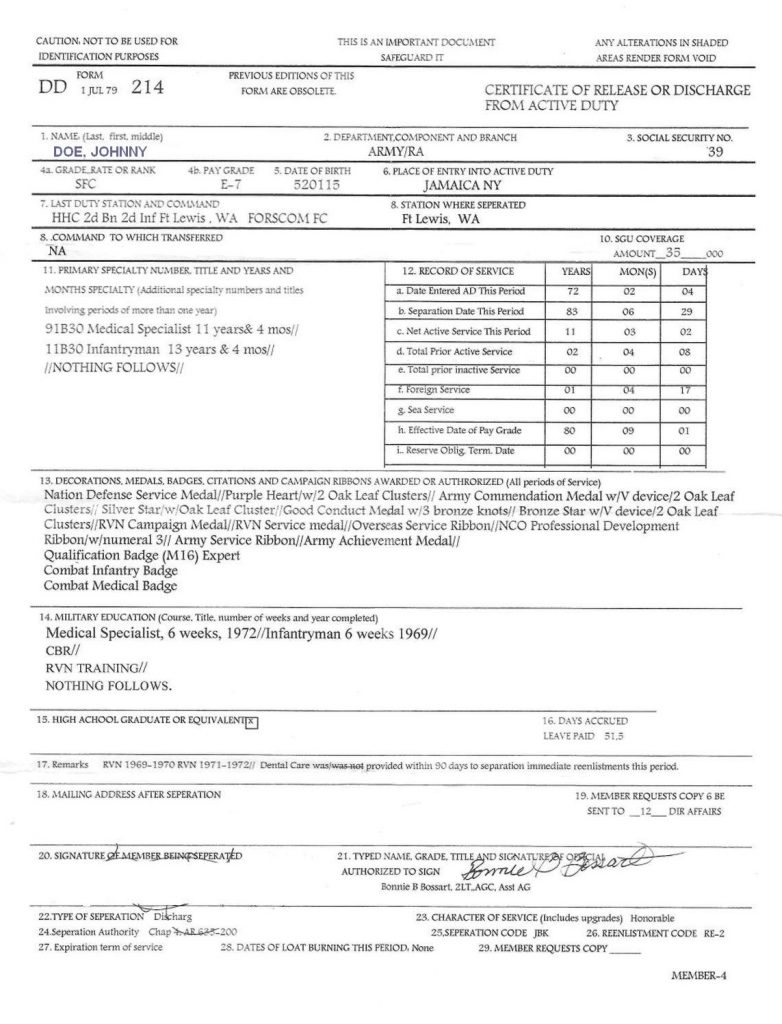

For the uninitiated, a DD 214 is a one page summary issued by the military to service members upon discharge. Its itemized boxes display personal data, dates of service, military skills, awards and decorations, disciplinary actions, combat campaigns, geographic assignments. It is used to apply for veteran’s benefits. Or to verify military service for employer’s. The document is part of a service members 201 file, or Official Military Personnel File (OMPF), a detailed administrative record of a soldier’s time in service.

But this was the same copy he’d shown me three years back, listing two Silver Stars, three Bronze Stars, three Purple Hearts, the Combat Infantry Badge, the Combat Medic Badge, Vietnam campaign ribbons, several non valor medals. What to do? I withheld my disappointment, instead offered thanks.

“It’s another part of the puzzle,” I said, “but look, the social security number is off by one digit. The word “separation” is misspelt three times. The dates of service don’t add up.”

Flustered, Johnny quickly rebounded. He’d incorrectly filled out the SF 180 form Martin used to obtain his OMPF in 2013. “I wrote in the wrong social security number. That’s what happened. I feel like shooting myself,” he exclaimed. But that made no sense. Should I pounce on him? Let it pass? We continued amicably.

The heart of the matter was the OMPF sent by NPRC, which did not mention his dozen combat medals, or two tours in Vietnam. “I don’t know what to say,” said Johnny. “I was there. I earned those medals. That’s the god’s honest truth.”

It was possible, I said, that clerks in his combat unit kept poor records, or that after the war, pages from his file were lost. This was not uncommon, a military archivist told me when I visited the National Archives in 2000.

Or stateside clerks at his last duty station might have erred. In that case, a special army board might amend his records. Could I do that for him? “No,” said Johnny. He would do that himself. Could I have a copy of the 214 he’d just shown me? “No,” he said, firmly. He never doubted the word of a combat vet, and up to now, no one had doubted him.

“It feels weird, unjustified. I don’t want to start a precedent with myself,” he said.

On his own, or with help, he would sort things out.

An hour had passed. The bit of tension between us lightened. Johnny accepted my offer to locate men who might support his VA disability claim for wounds sustained in combat: a Native American pointman. Two grunts in Idaho, a third grunt in Texas who’d saved his life. The act of recalling names and faces lead Johnny to tell several stories.

The enemy occasionally shelled a large base in Pleiku. “Just to let us know,” he muttered. And when the shells exploded, Jerome the monkey, tied to a metal post by a long leash, would run to the highest stack of sandbags, screech loudly, and masturbate. “Happened every time,” said Johnny. “You could count on it.” He chuckled and slapped his thigh.

The enemy occasionally shelled a large base in Pleiku. “Just to let us know,” he muttered. And when the shells exploded, Jerome the monkey, tied to a metal post by a long leash, would run to the highest stack of sandbags, screech loudly, and masturbate. “Happened every time,” said Johnny. “You could count on it.” He chuckled and slapped his thigh.

During an attack on the same base, a man’s leg had been blown off. To stop the bleeding, Johnny tapped the end of the exposed brachial artery with his finger tip. This caused the blood vessel to retract slightly, stanching the flow of blood. He had learned the trick from a senior medic. Minutes later, a bullet whizzed right through  Johnny’s helmet!

Johnny’s helmet!

Mournfully, Johnny recalled the sight of a baby’s skull impaled on a bamboo stake. He despaired that the infant had not been properly buried. “Unlike WWII vets,” he said, “I’m just telling it like it is.”

Home from war, stationed in the Pacific Northwest, one morning Johnny grappled with a fractious lieutenant. In a burst of rage, he pummeled the officer, breaking three of his ribs, cracking an arm, flattening his nose.

The next day, surrounded by senior officers, General John Shalikashvili, (the future Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff), having reviewed Johnny’s personnel file, declined to court martial him. “Not with those medals”, said the general, (which Johnny paused to recite). To be that violent, said the general, something must have set Johnny off.

“He made me a deal,” said Johnny. “He clicked his pen, and handed me a sheet of paper. ‘Sign here, son. I’ll have you out in twenty-four hours.’ ”

In no time Johnny was honorably discharged.

True, fabricated or embellished, Johnny Doe is a consummate raconteur. His tone is exquisite, his timing, lyrical; every word falls into place. Yet each war story or post war tale is a bit too perfect, or too fantastic to believe.

An hour later we confirmed that if necessary, Johnny would contact Senator X. “It will be nice to have this over,” he said. In good faith, I offered to edit a part of my website version of the CounterPunch article which seemed harsh. We walked to the front door, shook hands, and parted.

The sun was setting. In the chilly air I headed to Chinatown for a meal of dumplings and sweet rolls. Afterward, I stopped at a store front to observe a middle aged man practicing t’ai chi. He had memorized the ancient forms, but seemed hesitant, anxious, unable to move without thinking.

The sun was setting. In the chilly air I headed to Chinatown for a meal of dumplings and sweet rolls. Afterward, I stopped at a store front to observe a middle aged man practicing t’ai chi. He had memorized the ancient forms, but seemed hesitant, anxious, unable to move without thinking.

The following month, at a local Veterans for Peace meeting, my friend Martin responded to questions about Johnny, a prominent member. He cited my CounterPunch article. None present had heard of it. Emails flew. Why hadn’t they known these facts? What was Johnny hiding?

Johnny issued a statement citing his numerous ribbons, his of years fighting PTSD. At the next meeting, he would present the 214 obtained by Senators X and Y. The very document I disputed.

I called Senator Y’s office. Staff declined to comment. Senator X’s staff said Johnny had  contacted the office several times but they had never assisted him with military matters. At my request the staffer checked three times. Sorry, she said, no veteran’s assistance on file.

contacted the office several times but they had never assisted him with military matters. At my request the staffer checked three times. Sorry, she said, no veteran’s assistance on file.

Johnny provided another DD 214. It contained new mistakes.

Weeks passed. Bruce’s attempted head lock still bothered me. I had defeated this mans hate, but the encounter had triggered old memories: a violent mugging in New Jersey; an assault in New York. Following an attempt on my life in New Jersey, three days in ICU. Vietnam.

I contacted fake vet expert B.G. Burkett. “No evidence of Vietnam service,” he said, after reviewing Johnny’s OMPF. He sent for an Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) summary of Johnny’s military record.

I contacted fake vet expert B.G. Burkett. “No evidence of Vietnam service,” he said, after reviewing Johnny’s OMPF. He sent for an Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) summary of Johnny’s military record.

Two weeks later, the VFP chapter offered Johnny a deal,“Give us the authority to obtain your 214 from the National Personnel Records Center. We’ll compare it with the one you’ve shown us. If the documents match, the issue is settled. If not, you’ll have to resign.” Bowing to pressure, Johnny agreed.

More than three years had passed since Martin had obtained Johnny’s records. Why duplicate his efforts? And what of the FOIA documents obtained by Burkett? It didn’t matter. To everyone’s surprise, in a fit of anger Johnny reversed himself. He would not cooperate with VFP. Instead, his lawyers would sue Martin and I for libel.

Despite the controversy, many in the VFP chapter admired Johnny’s activist spirit. They valued his loyalty and friendship. His war record was a private affair; he alone should resolve it. Since Johnny claimed he had previously sent his 214 to VFP’s national office, the chapter absolved itself from the matter.

But Johnny had not sent his 214 anywhere. On file at the national office was a link to a defunct website which contained several essays for a proposed anthology edited by Martin. Among them were Johnny’s handsome war tales.

Bruce reversed himself. Johnny should stand down until genuine documents were in hand. Johnny resigned, then un-resigned, with Bruce shouting “Never submit to your detractors!”

One day before the Ides of March, citing personal issues, Johnny again called it quits. The chapter accepted his resignation. Johnny reversed himself. He would provide new evidence.

Meetings were held to sort things out:

-Johnny presented a new DD 214. When irregularities were pointed out, indicating it was fake, he threw up his hands and shouted “I quit!”

-Bruce held up the Senator’s letter which asserted the documents were real.

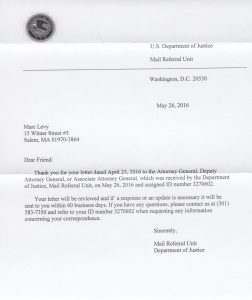

-Johnny let it be known that Justice Department lawyers were investigating whether Martin or I had accessed his records illegally.

-Brandishing a beer bottle, Bruce threatened a member unsympathetic to Johnny. “I’m gonna mess you up good,” he scowled. Said the unsympathizer in an email to this writer, “It left an unmistakable feeling that things were just beginning, not ending.”

In June 2016 I spoke with Burkett. We reviewed Johnny’s OMPF, suspect documents, the alleged assistance from Senator’s X and Y. I noted that Johnny and Bruce had contacted a third Senator, who would request yet another 214 from NRPC.

“The con is the real problem,” said Burkett. Under the current Stolen Valor Act, it’s a crime to use fake documents to obtain VA benefits a veteran is not entitled to. Johnny and Bruce had long maintained that Johnny saw VA therapists and had attended VA therapy groups for PTSD.

Johnny once told me he’d registered a copy of his 214 with a county clerk in New York. I wrote to the clerk. The reply was swift. Recall that Johnny claimed Senators X and Y had obtained the document from that very office.

Were Martin and I really being investigated for illegally accessing Johnny’s military records? I assumed not, but DOJ said it could not release that information. I had to contact the FBI!

Were Martin and I really being investigated for illegally accessing Johnny’s military records? I assumed not, but DOJ said it could not release that information. I had to contact the FBI!

I learned that many VFP members felt that Johnny seemed emotionally troubled; he had physical problems too. The chapter was deeply divided over what to do.

I’d lost sight of Johnny’s frailness. If anything, he is the opposite of his mythic self. When we last spoke in late 2016, he appeared sad, defeated, fragile. Overweight, Johnny walked slowly; in conversation, except for occasional bright spots, he seemed weary. From time to time he forgot his train of thought. A distinct emptiness pervaded his war tales, as if his sorrow resided not in combat, but in love lost, or childhood trauma, some distant shock. In that case, Johnny’s conjurings deserved sympathy, not scorn.

Hoping to know Johnny better, to spend time with him, to understand what made him tick, I had followed up our meeting with emails and phone calls; he did not reply.

I never heard back from Burkett about his FOIA request. It didn’t matter. The VFP chapter released an email which summed things up:

“It is the understanding of the Executive Committee that the most recent version of Johnny Doe’s DD 214 received from the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in St. Louis, and viewed by members Bruce and Greg, proves that his record of service in Vietnam and related medals are false. He is, however, an Army veteran and has been requested to admit what he has done and make a sincere apology to the chapter. In the absence of such, the Executive Committee has voted to move for his expulsion from the chapter at our September general meeting. As for his membership status, that remains for the national board to decide.”

In response, Johnny declared NPRC had the wrong social security number; that was not his DD 214! It belonged to someone else! He would request new documents!

During this time NARA replied to a FOIA request I had previously sent them. As expected, Johnny’s OMPF summary contained no record of service in Vietnam.

Less than a week later Martin and I received an email from a VFP national board member. He had read my CounterPunch article; appointed to head an investigative committee, he asked if Johnny Doe was a combat vet. I sent him all Johnny’s records, and stated my conclusion. The board member pointed out a minor OMPF/FOIA typo. Corrected, everything lined up. Against Johnny.

There were additional fractious meetings. Johnny resigned yet again. Finally, in October 2016 the chapter voted that until Johnny presented valid documents of his service he was expelled. Not long after, the national board followed suit.

Plenty of anti-war or veterans rights activists aren’t  combat vets. While combat brings unique insight and credibility, it isn’t a requirement for caring or being politically engaged. It’s unfortunate that Johnny hasn’t come to terms with that. He could have apologized. Like Bruce did.

combat vets. While combat brings unique insight and credibility, it isn’t a requirement for caring or being politically engaged. It’s unfortunate that Johnny hasn’t come to terms with that. He could have apologized. Like Bruce did.

Instead, on radio station WZBC in Boston, 90.3 on your FM dial, Johnny hosts the aptly named Truth and Justice Show, where he claims to be a Vietnam veteran.

update-July 2018

Informed of Johnny Doe’s suspect record and expulsion from Veterans for Peace, WZBC station manager Jackie Foley noted the station had heard rumors about Johnny, but felt that his heart was in the right place. VFP stated that since Johnny no longer touted his claimed valor medals, and having expelled him, his behavior did not concern them.

Johnny Doe: Case Closed…

“You must remember what you are and what you have chosen to become, and the significance of what you are doing. There are wars and defeats and victories of the human race that are not military and that are not recorded in the annals of history. Remember that while you’re trying to decide what to do.” —John Williams, Stoner

CounterPunch readers may recall “The Curious Case of Johnny Doe”, my 2015 story about a popular local veteran who loudly claimed two tours in Vietnam and fistfuls of medals. The article all but unmasked him as fake.

For several months I set Johnny Doe aside, but the old itch–was the man real or not–returned, when I stumbled across a video of Johnny recounting his tales of valor. This was no amateur film. The lighting, angles, pans, and segues bore the hallmarks of a professional.

I complimented the filmmaker on his skill, but noted that his subject was suspect. The film maker contacted Johnny’s ardent supporter and best friend, Bruce. An excerpt from Bruce’s response is enlightening:

Months later, one cold winter night in 2016, at a cozy Quaker meetinghouse, the unexpected reared its head. As I was preparing to give a talk, Bruce stormed over to me, shook my hands, exclaimed we had to talk. For ten heated minutes, in a dimlit hallway, hidden from view, his reddening face inches from mine, he raged about my questioning Johnny, a superb soldier, a decorated hero. “How dare you!” He fumed. “How dare you!” I stood my ground, hoping he’d talk himself out. “We’re contacting Senator X,” he snarled. “We’ll get documents that will show you’re wrong!” “Good,” I countered. “I look forward to seeing them.” “Me too,” he snarled, then tried cuffing me in a headlock. I pushed him off. The confrontation ended. Rattled, my talk was second rate, the evening ruined.

Six weeks later, as I walked through a snow covered park, a shivering wind rustled the trees. I crossed a busy avenue, entered the building where Johnny and I had agreed to talk.

His small windowless office was filled by a shabby desk, a shelf of office supplies, piled clothes, a copy machine, two worn out black fabric chairs. The beige walls, save for a fading political poster, were vacant. Overhead fluorescent lights cast their harsh impersonal glow.

Johnny was friendly, welcoming. As we made small talk, he dawdled an envelope on his lap. I hoped it contained the document we had discussed by email and phone.

I reminded Johnny we’d both been combat medics in Vietnam. Shared various medals. Each of us strongly identified as Vietnam vets, spoke openly about and against war, remained troubled by it. I was not angry at him, I said. I respected him. But his peculiar war tales and numerous decorations had caught my eye. What began as curiosity had snowballed into a years long desire to know the truth. Did Johnny get his gun, or not?

We reviewed my 2015 CounterPunch article, which cited Johnny’s blazing war stories, multiple valor medals, his suspect DD 214, his archived military records, which Johnny had reluctantly authorized my friend Martin to obtain from the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in St. Louis. All led to serious doubts he’d ever served in combat. And yet, I noted, there were grey areas.

For example, Johnny knew about weaponry, areas of operation, knew how grunts talked, what we did on patrol.

I opened the envelope and was saddened by what I saw: an undated form letter, apparently ink jet printed, from Senator X, which thanked Johnny for his service. It cited Senator Y’s help, and cited the enclosed DD 214, retrieved from a court house in New York. A VA memo confirmed the senators’ document request.

For the uninitiated, a DD 214 is a one page summary issued by the military to service members upon discharge. Its itemized boxes display personal data, dates of service, military skills, awards and decorations, disciplinary actions, combat campaigns, geographic assignments. It is used to apply for veteran’s benefits. Or to verify military service for employer’s. The document is part of a service members 201 file, or Official Military Personnel File (OMPF), a detailed administrative record of a soldier’s time in service.

But this was the same copy he’d shown me three years back, listing two Silver Stars, three Bronze Stars, three Purple Hearts, the Combat Infantry Badge, the Combat Medic Badge, Vietnam campaign ribbons, several non valor medals. What to do? I withheld my disappointment, instead offered thanks.

“It’s another part of the puzzle,” I said, “but look, the social security number is off by one digit. The word “separation” is misspelt three times. The dates of service don’t add up.”

Flustered, Johnny quickly rebounded. He’d incorrectly filled out the SF 180 form Martin used to obtain his OMPF in 2013. “I wrote in the wrong social security number. That’s what happened. I feel like shooting myself,” he exclaimed. But that made no sense. Should I pounce on him? Let it pass? We continued amicably.

The heart of the matter was the OMPF sent by NPRC, which did not mention his dozen combat medals, or two tours in Vietnam. “I don’t know what to say,” said Johnny. “I was there. I earned those medals. That’s the god’s honest truth.”

It was possible, I said, that clerks in his combat unit kept poor records, or that after the war, pages from his file were lost. This was not uncommon, a military archivist told me when I visited the National Archives in 2000.

Or stateside clerks at his last duty station might have erred. In that case, a special army board might amend his records. Could I do that for him? “No,” said Johnny. He would do that himself. Could I have a copy of the 214 he’d just shown me? “No,” he said, firmly. He never doubted the word of a combat vet, and up to now, no one had doubted him.

“It feels weird, unjustified. I don’t want to start a precedent with myself,” he said.

On his own, or with help, he would sort things out.

An hour had passed. The bit of tension between us lightened. Johnny accepted my offer to locate men who might support his VA disability claim for wounds sustained in combat: a Native American pointman. Two grunts in Idaho, a third grunt in Texas who’d saved his life. The act of recalling names and faces lead Johnny to tell several stories.

During an attack on the same base, a man’s leg had been blown off. To stop the bleeding, Johnny tapped the end of the exposed brachial artery with his finger tip. This caused the blood vessel to retract slightly, stanching the flow of blood. He had learned the trick from a senior medic. Minutes later, a bullet whizzed right through Johnny’s helmet!

Johnny’s helmet!

Mournfully, Johnny recalled the sight of a baby’s skull impaled on a bamboo stake. He despaired that the infant had not been properly buried. “Unlike WWII vets,” he said, “I’m just telling it like it is.”

Home from war, stationed in the Pacific Northwest, one morning Johnny grappled with a fractious lieutenant. In a burst of rage, he pummeled the officer, breaking three of his ribs, cracking an arm, flattening his nose.

The next day, surrounded by senior officers, General John Shalikashvili, (the future Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff), having reviewed Johnny’s personnel file, declined to court martial him. “Not with those medals”, said the general, (which Johnny paused to recite). To be that violent, said the general, something must have set Johnny off.

“He made me a deal,” said Johnny. “He clicked his pen, and handed me a sheet of paper. ‘Sign here, son. I’ll have you out in twenty-four hours.’ ”

In no time Johnny was honorably discharged.

True, fabricated or embellished, Johnny Doe is a consummate raconteur. His tone is exquisite, his timing, lyrical; every word falls into place. Yet each war story or post war tale is a bit too perfect, or too fantastic to believe.

An hour later we confirmed that if necessary, Johnny would contact Senator X. “It will be nice to have this over,” he said. In good faith, I offered to edit a part of my website version of the CounterPunch article which seemed harsh. We walked to the front door, shook hands, and parted.

The following month, at a local Veterans for Peace meeting, my friend Martin responded to questions about Johnny, a prominent member. He cited my CounterPunch article. None present had heard of it. Emails flew. Why hadn’t they known these facts? What was Johnny hiding?

Johnny issued a statement citing his numerous ribbons, his of years fighting PTSD. At the next meeting, he would present the 214 obtained by Senators X and Y. The very document I disputed.

I called Senator Y’s office. Staff declined to comment. Senator X’s staff said Johnny had contacted the office several times but they had never assisted him with military matters. At my request the staffer checked three times. Sorry, she said, no veteran’s assistance on file.

contacted the office several times but they had never assisted him with military matters. At my request the staffer checked three times. Sorry, she said, no veteran’s assistance on file.

Johnny provided another DD 214. It contained new mistakes.

Weeks passed. Bruce’s attempted head lock still bothered me. I had defeated this mans hate, but the encounter had triggered old memories: a violent mugging in New Jersey; an assault in New York. Following an attempt on my life in New Jersey, three days in ICU. Vietnam.

Two weeks later, the VFP chapter offered Johnny a deal,“Give us the authority to obtain your 214 from the National Personnel Records Center. We’ll compare it with the one you’ve shown us. If the documents match, the issue is settled. If not, you’ll have to resign.” Bowing to pressure, Johnny agreed.

More than three years had passed since Martin had obtained Johnny’s records. Why duplicate his efforts? And what of the FOIA documents obtained by Burkett? It didn’t matter. To everyone’s surprise, in a fit of anger Johnny reversed himself. He would not cooperate with VFP. Instead, his lawyers would sue Martin and I for libel.

Despite the controversy, many in the VFP chapter admired Johnny’s activist spirit. They valued his loyalty and friendship. His war record was a private affair; he alone should resolve it. Since Johnny claimed he had previously sent his 214 to VFP’s national office, the chapter absolved itself from the matter.

But Johnny had not sent his 214 anywhere. On file at the national office was a link to a defunct website which contained several essays for a proposed anthology edited by Martin. Among them were Johnny’s handsome war tales.

Bruce reversed himself. Johnny should stand down until genuine documents were in hand. Johnny resigned, then un-resigned, with Bruce shouting “Never submit to your detractors!”

One day before the Ides of March, citing personal issues, Johnny again called it quits. The chapter accepted his resignation. Johnny reversed himself. He would provide new evidence.

Meetings were held to sort things out:

-Johnny presented a new DD 214. When irregularities were pointed out, indicating it was fake, he threw up his hands and shouted “I quit!”

-Bruce held up the Senator’s letter which asserted the documents were real.

-Johnny let it be known that Justice Department lawyers were investigating whether Martin or I had accessed his records illegally.

-Brandishing a beer bottle, Bruce threatened a member unsympathetic to Johnny. “I’m gonna mess you up good,” he scowled. Said the unsympathizer in an email to this writer, “It left an unmistakable feeling that things were just beginning, not ending.”

In June 2016 I spoke with Burkett. We reviewed Johnny’s OMPF, suspect documents, the alleged assistance from Senator’s X and Y. I noted that Johnny and Bruce had contacted a third Senator, who would request yet another 214 from NRPC.

“The con is the real problem,” said Burkett. Under the current Stolen Valor Act, it’s a crime to use fake documents to obtain VA benefits a veteran is not entitled to. Johnny and Bruce had long maintained that Johnny saw VA therapists and had attended VA therapy groups for PTSD.

Johnny once told me he’d registered a copy of his 214 with a county clerk in New York. I wrote to the clerk. The reply was swift. Recall that Johnny claimed Senators X and Y had obtained the document from that very office.

I learned that many VFP members felt that Johnny seemed emotionally troubled; he had physical problems too. The chapter was deeply divided over what to do.

I’d lost sight of Johnny’s frailness. If anything, he is the opposite of his mythic self. When we last spoke in late 2016, he appeared sad, defeated, fragile. Overweight, Johnny walked slowly; in conversation, except for occasional bright spots, he seemed weary. From time to time he forgot his train of thought. A distinct emptiness pervaded his war tales, as if his sorrow resided not in combat, but in love lost, or childhood trauma, some distant shock. In that case, Johnny’s conjurings deserved sympathy, not scorn.

Hoping to know Johnny better, to spend time with him, to understand what made him tick, I had followed up our meeting with emails and phone calls; he did not reply.

I never heard back from Burkett about his FOIA request. It didn’t matter. The VFP chapter released an email which summed things up:

“It is the understanding of the Executive Committee that the most recent version of Johnny Doe’s DD 214 received from the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in St. Louis, and viewed by members Bruce and Greg, proves that his record of service in Vietnam and related medals are false. He is, however, an Army veteran and has been requested to admit what he has done and make a sincere apology to the chapter. In the absence of such, the Executive Committee has voted to move for his expulsion from the chapter at our September general meeting. As for his membership status, that remains for the national board to decide.”

In response, Johnny declared NPRC had the wrong social security number; that was not his DD 214! It belonged to someone else! He would request new documents!

During this time NARA replied to a FOIA request I had previously sent them. As expected, Johnny’s OMPF summary contained no record of service in Vietnam.

Less than a week later Martin and I received an email from a VFP national board member. He had read my CounterPunch article; appointed to head an investigative committee, he asked if Johnny Doe was a combat vet. I sent him all Johnny’s records, and stated my conclusion. The board member pointed out a minor OMPF/FOIA typo. Corrected, everything lined up. Against Johnny.

There were additional fractious meetings. Johnny resigned yet again. Finally, in October 2016 the chapter voted that until Johnny presented valid documents of his service he was expelled. Not long after, the national board followed suit.

Plenty of anti-war or veterans rights activists aren’t combat vets. While combat brings unique insight and credibility, it isn’t a requirement for caring or being politically engaged. It’s unfortunate that Johnny hasn’t come to terms with that. He could have apologized. Like Bruce did.

combat vets. While combat brings unique insight and credibility, it isn’t a requirement for caring or being politically engaged. It’s unfortunate that Johnny hasn’t come to terms with that. He could have apologized. Like Bruce did.

Instead, on radio station WZBC in Boston, 90.3 on your FM dial, Johnny hosts the aptly named Truth and Justice Show, where he claims to be a Vietnam veteran.

update-July 2018

Informed of Johnny Doe’s suspect record and expulsion from Veterans for Peace, WZBC station manager Jackie Foley noted the station had heard rumors about Johnny, but felt that his heart was in the right place. VFP stated that since Johnny no longer touted his claimed valor medals, and having expelled him, his behavior did not concern them.