Christmas 1970: a hot meal in a muddy fox hole, a Red Cross gift of WD 40. Excellent for cleaning my M16. Thank you, Jesus.

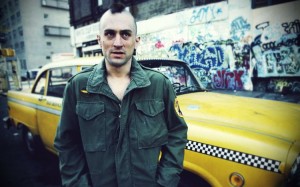

Twelve months later, three on a remote fire base burning human shit, it was time to head home. At Bien Hoi Airport I met other GIs leaving Vietnam, some with combat ribbons, the thousand yard stare. Unlike the young men who flirted with stewardesses, fell asleep, then suddenly woke in Vietnam, our return flight was eerily quiet. But the moment we landed at Oakland Air Force Base everyone cheered.

At the airport, I bought a plane ticket to Jersey, boarded, and sat near a good looking stewardess. She winked and giggled but I did not reply. The cab ride home cost six dollars.

“This is my son,” my old man would say to friends and strangers. “He was in Vietnam. He was a medic.”

But my Dad, my brother, my friends, none asked what I did in war, what war did to me. Never asked.

A month later, in the dead of a brutal winter, I reported to Fort Devens.

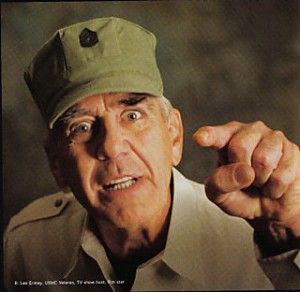

“Sorry,” I said to First Sergeant Albert Weiner, an intense and vigorous man. “I don’t pull guard duty.”

“You don’t what?” he asked, stupefied.

“Nothing personal, Sarge. I just can’t do it.”

A year at war can change you.

“You got thirty minutes,” the First Sergeant scowled as he stormed out the ba rrack. “You best have your shit together!”

rrack. “You best have your shit together!”

He really said that, “Best have your shit together.”

I packed an AWOL bag, put on jeans, sneakers, a gray sweatshirt, my army field jacket, and lay back in my bunk.

“What the… Where the hell are you going?” the First Sergeant asked as I got up to leave.

“AWOL, Sarge. I don’t pull guard duty. Remember?”

“Are you out of your mind?” he shrieked. “You can’t do that!”

“I’m going to Boston, Sarge. See you in three days.”

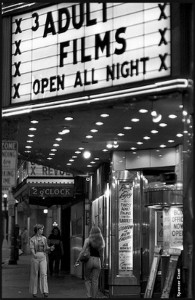

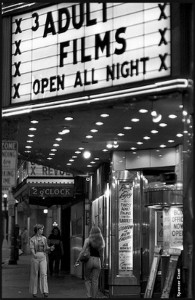

I walked out the barrack, caught a bus, two hours later had a ten-dollar hotel room, went to a porn theater, jerked off, ate good, slept good, explored the town. The trip back to Devens so uneventful.

“Greetings,” I said to the company clerk, who glanced up from his typewriter.

“Greetings yourself,” he said. “Weiner gave you an Article 15.”

But non judicial punishment meant nothing to this GI. For the next six months I refused guard duty, KP, haircuts, I did not salute officers. And deliberately failed a driving test.

“Stop sign! Stop sign! Step on the brakes!” a lieutenant wailed.

“Stop sign! Stop sign! Step on the brakes!” a lieutenant wailed.

I stepped on the gas.

“Green means go! GO, you moron!”

I stepped on the brakes.

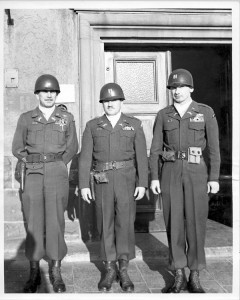

Over time I racked up five Article 15s and a Summary Court Martial. The company commander, Captain John Scarlotti, assigned me to Sgt. Green, a gigantic muscular man who’d done three tours in Nam and won three Silver Stars. His orders were to make me miserable.

“Get back to work or I’ll give you a knuckle sandwich,” he barked one fine summer day.

Calmly, I strode past the big man, left the sweltering warehouse, walked to the middle of a small field, sat down cross-legged and began singing “The Answer Is Blowing In The Wind.”

Sgt. Green called First Sergeant Weiner, who called Captain Scarlotti, who called the Battalion Commander, Major Odell.

“Now what?” asked the Captain, who swept both hands through his thinning gray hair.

“Sir, I don’t eat knuckle sandwiches,” I said, and calmly stretched my legs.

Captain Scarlotti sank his face into his hands.

Major Odell, a stocky middle-aged Texan, leaned over me. “Son,” he said. “Something’s bothering you. Tell me what’s on your mind. I swear to God I’ll listen. Every word…every goddamn word you say.”

“Sir,” I said, and nearly stood and saluted. “I can’t follow orders. I just can’t. I want out of the Army.”

The major was not pleased.

“Now you listen here, Private,” he said. “As long as you’re in the Army you will obey orders! If not…” And he shook his head and thundered, “I will court-martial your fucking ass!”

“Now you listen here, Private,” he said. “As long as you’re in the Army you will obey orders! If not…” And he shook his head and thundered, “I will court-martial your fucking ass!”

He really said that, “…your fucking ass!”

Thank you, Jesus for the Common Sense Book Store, a GI coffee house located just off base in the sleepy town of Ayer. Here, GIs could speak out without fear of harassment. Once a week, a Boston University English professor David Rubin us taught creative writing and poetry. In time, we formed”Radio Free Devens”, an anti-war radio show broadcast by WAAF in Worcester, MA. We gave interviews to reporters. One night in Cambridge I shook hands with Dan Ellsburg on Eye Witness News. I returned to base late. The next morning, I was called to the Orderly Room.

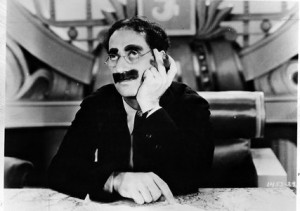

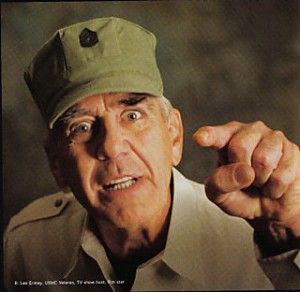

“Was that your ugly face I saw on TV?” asked First Sergeant Elliot Johnson, a barrel-chested black man who’d fought his way up the Army’s lily white ranks. Framed certificates and awards blanketed the wall behind his government issue desk.

“Was that your ugly face I saw on TV?” asked First Sergeant Elliot Johnson, a barrel-chested black man who’d fought his way up the Army’s lily white ranks. Framed certificates and awards blanketed the wall behind his government issue desk.

I nodded sheepishly.“Yes, First Sergeant.”

Unlike First Sergeant Weiner, who had retired, First Sergeant Johnson looked at me with the kindness of one who has survived much cruelty but will not bestow it.

“You’re a crazy one,” he said. “Someone’s gonna write a book about you. Make you famous. I mean that. Now get the fuck out of my office!”

Restricted to base by Captain Scarlotti, I filed for conscientious objector status. Denied, I wrote my to congressman: “Help! I need to get out of the Army!” When he did not reply, I began the long trek up the Fort Devens chain-of-command. Two months later I reached the top.

“Sir, Private Levy reporting to see General Irzyk,” I said to a trim lieutenant seated behind an immaculate gray desk.

“Sir, Private Levy reporting to see General Irzyk,” I said to a trim lieutenant seated behind an immaculate gray desk.

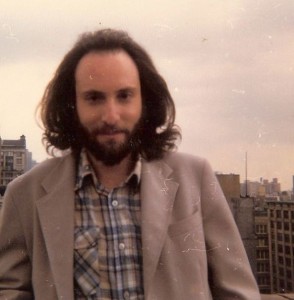

By now my hair was shoulder length; my garrison cap kept slipping off my head.

Lieutenant Shaw reluctantly called the General. After a brief exchange, he slammed down the phone. “The General can’t see you today,” he snarled.

“But sir,” I pleaded, “I’m Private Levy. I have an appointment! I’m here to get out of the Army.”

In one cruel motion, Lieutenant Shaw stood and pounded the desk with his fist. “I don’t think you get it, bud. The General will not see you. Now get the fuck out!”

And he really said that.

Three weeks later an officer approached me as I stood in the morning chow line.

“Sign here,” he said, pointing to a large X be neath a dozen paragraphs. “We’ll give you a Bad Conduct Discharge. You’ll be out in a week! Isn’t that what you want?”

neath a dozen paragraphs. “We’ll give you a Bad Conduct Discharge. You’ll be out in a week! Isn’t that what you want?”

A Bad Conduct Discharge, a BCD in Army parlance, is a very bad thing to possess. It identifies the bearer as a person without pride, without honor or scruples, a pariah incapable of serving his country. It also disqualifies the recipient from most state and federal benefits. It is a bright red flag to potential employers. It condemns one to a life of civilian hell.

I looked at the document, then looked at the lieutenant. “No thank you, sir. I’ll take my chances at the Special court-martial.”

The officer was stunned. I was hungry. Drifting from the chow hall, the scent of burnt toast and runny eggs did not decrease my appetite.

One month lat er, a tall, one-eyed colonel threw me out of JAG.

er, a tall, one-eyed colonel threw me out of JAG.

“Sir, you can’t do that. Major Odell has me up for a Special court-martial for refusing to obey orders. I’m here to see Captain Lamarine, my Army lawyer.”

A decorated WW II vet, Colonel Ray Ritter wore a jaunty black eye patch. Cocking his head slightly to the left, he looked me over. “You’re a fucking disgrace to the Army!” he said, and grabbed me by the shoulders and hustled me out of the building. “A fucking disgrace!”

Undeterred, I walked a mile to the Inspector General’s office.  A swarthy heavy set man, the general leaned back in his large oak chair, and propped both his legs on a massive wood desk.

A swarthy heavy set man, the general leaned back in his large oak chair, and propped both his legs on a massive wood desk.

“What can I do for you, soldier?”asked IG Schmidt.

“Sir, Colonel Ritter just threw me out of JAG.”

I told IG Schmidt my story while standing at attention in my dress uniform. I had given up on garrison caps, and today wore an Army baseball hat to which I’d painted an officer’s gold oak leaf trim.

The IG looked me over, lit a cigar, and took a long, thoughtful drag. “I’ll look into it,” he said, exhaling a noxious plume.

“Thank you, Sir! Thank you!” I said. I really believed him.

When I returned to company  Head Quarters, Captain Scarlotti screamed, “The IG just chewed my ass out! Did you complain about Colonel Ritter? Did you really do that?!?!”

Head Quarters, Captain Scarlotti screamed, “The IG just chewed my ass out! Did you complain about Colonel Ritter? Did you really do that?!?!”

“Sir, you don’t understand. I’m Private Levy. I have a right to legal counsel.”

The captain was furious. “Get the fuck out of my sight!” he yelled at the top of his lungs.“You hear me! Get the fuck out!”

My friends at the Common Sense book store contacted Stan Lapon, a noted civilian attorney. Stan agreed to take my case. Hearing the good news, I went AWOL to Jersey. One night the phone rang. My old man picked it up. “It’s for you,” he said.

“Hello…” I said, tentatively. I wasn’t expecting any calls.

“Doc, it’s Stan. Where are you? Why’d you leave?”

“I’m home, Stan. It’s my birthday. I’m twenty-one.”

“Well, I suppose I have a present for you. Army brass want to give you a Dishonorable Discharge, and three months’ hard labor. But I know someone. They pulled some strings. Plead guilty, serve five days in jail, they’ll give you a General Discharge.”

I looked at my dog. My dog looked at me.

“I don’t know, Stan. What do you think?”

“If I were you, Doc,” he said, “I’d take it.”

“OK, Stan. See you soon.”

We met in an empty JAG office an hour before the proceedings. Looking around, I noticed two stacks of paper on a long metal desk. One pile had copies of my case. The other concerned a General court-martial, the most serious level of military courts, reserved for felony and capital crimes. I read the top page. The charge was statutory rape. The accused was the muscular giant Sergeant Green.

desk. One pile had copies of my case. The other concerned a General court-martial, the most serious level of military courts, reserved for felony and capital crimes. I read the top page. The charge was statutory rape. The accused was the muscular giant Sergeant Green.

After two hours in a tiny courtroom, five officers pronounced the sentence Stan had predicted. Before two imposing MPs lead me away, the court secretary, a shapely brunette, slipped me a tab of Speed.

In the stockade barbershop, one of the MPs said, “Boy, you gonna co-operate or we gonna hold you down?”

The two of them outweighed me by half a ton. “I’ll co-operate,” I said.

My baseball cap was summarily knocked off my head. The prison barber cut my hair to the bone. A photographer snapped my picture with a Polaroid camera. When he wasn’t looking, I pocketed the photo. I gave the Speed to a combat vet who’d slugged an officer, knocking him out.

Five days later I was freed from jail. In the rush to justice, Stan forgot to mention I’d lose all rank and a months pay. Nearly broke, I packed my Army duffle bag, walked past the main gate, said good-bye to Devens, and started hitching to Boston. About noon a red Chevy convertible pulled over. A familiar face leaned out the driver side window.

“Need a lift?” asked the court secretary.

The next morning, after one last fondle and a fond farewell, I began the long trip home.

Addendum

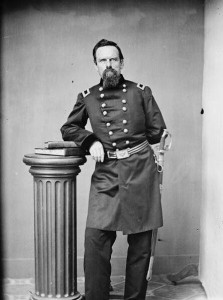

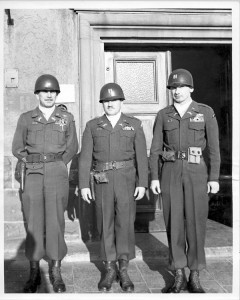

General Albin Felix Irzyk (January 2, 1917 – September 10, 2018) commanded the 8th Tank Battalion of the 4th Armored Division in WWII, the 14th Armored Cavalry Regiment during the Berlin Crisis of 1961, and was Assistant Commander of the 4th Infantry Division in South Vietnam. Devens was his last post. Medic wrote to him in 2009, and apologized for his long ago errant behavior. The general did not recall the events, instead wished me well, and sent two signed copies of his books.

How I Nearly Won the War

Christmas 1970: a hot meal in a muddy fox hole, a Red Cross gift of WD 40. Excellent for cleaning my M16. Thank you, Jesus.

Twelve months later, three on a remote fire base burning human shit, it was time to head home. At Bien Hoi Airport I met other GIs leaving Vietnam, some with combat ribbons, the thousand yard stare. Unlike the young men who flirted with stewardesses, fell asleep, then suddenly woke in Vietnam, our return flight was eerily quiet. But the moment we landed at Oakland Air Force Base everyone cheered.

At the airport, I bought a plane ticket to Jersey, boarded, and sat near a good looking stewardess. She winked and giggled but I did not reply. The cab ride home cost six dollars.

“This is my son,” my old man would say to friends and strangers. “He was in Vietnam. He was a medic.”

But my Dad, my brother, my friends, none asked what I did in war, what war did to me. Never asked.

A month later, in the dead of a brutal winter, I reported to Fort Devens.

“Sorry,” I said to First Sergeant Albert Weiner, an intense and vigorous man. “I don’t pull guard duty.”

“You don’t what?” he asked, stupefied.

“Nothing personal, Sarge. I just can’t do it.”

A year at war can change you.

“You got thirty minutes,” the First Sergeant scowled as he stormed out the ba rrack. “You best have your shit together!”

rrack. “You best have your shit together!”

He really said that, “Best have your shit together.”

I packed an AWOL bag, put on jeans, sneakers, a gray sweatshirt, my army field jacket, and lay back in my bunk.

“What the… Where the hell are you going?” the First Sergeant asked as I got up to leave.

“AWOL, Sarge. I don’t pull guard duty. Remember?”

“Are you out of your mind?” he shrieked. “You can’t do that!”

“I’m going to Boston, Sarge. See you in three days.”

I walked out the barrack, caught a bus, two hours later had a ten-dollar hotel room, went to a porn theater, jerked off, ate good, slept good, explored the town. The trip back to Devens so uneventful.

“Greetings,” I said to the company clerk, who glanced up from his typewriter.

“Greetings yourself,” he said. “Weiner gave you an Article 15.”

But non judicial punishment meant nothing to this GI. For the next six months I refused guard duty, KP, haircuts, I did not salute officers. And deliberately failed a driving test.

I stepped on the gas.

“Green means go! GO, you moron!”

I stepped on the brakes.

Over time I racked up five Article 15s and a Summary Court Martial. The company commander, Captain John Scarlotti, assigned me to Sgt. Green, a gigantic muscular man who’d done three tours in Nam and won three Silver Stars. His orders were to make me miserable.

“Get back to work or I’ll give you a knuckle sandwich,” he barked one fine summer day.

Calmly, I strode past the big man, left the sweltering warehouse, walked to the middle of a small field, sat down cross-legged and began singing “The Answer Is Blowing In The Wind.”

Sgt. Green called First Sergeant Weiner, who called Captain Scarlotti, who called the Battalion Commander, Major Odell.

“Now what?” asked the Captain, who swept both hands through his thinning gray hair.

“Sir, I don’t eat knuckle sandwiches,” I said, and calmly stretched my legs.

Captain Scarlotti sank his face into his hands.

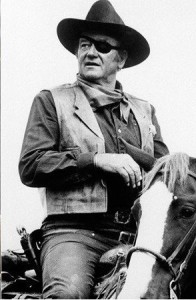

Major Odell, a stocky middle-aged Texan, leaned over me. “Son,” he said. “Something’s bothering you. Tell me what’s on your mind. I swear to God I’ll listen. Every word…every goddamn word you say.”

“Sir,” I said, and nearly stood and saluted. “I can’t follow orders. I just can’t. I want out of the Army.”

The major was not pleased.

He really said that, “…your fucking ass!”

Thank you, Jesus for the Common Sense Book Store, a GI coffee house located just off base in the sleepy town of Ayer. Here, GIs could speak out without fear of harassment. Once a week, a Boston University English professor David Rubin us taught creative writing and poetry. In time, we formed”Radio Free Devens”, an anti-war radio show broadcast by WAAF in Worcester, MA. We gave interviews to reporters. One night in Cambridge I shook hands with Dan Ellsburg on Eye Witness News. I returned to base late. The next morning, I was called to the Orderly Room.

I nodded sheepishly.“Yes, First Sergeant.”

Unlike First Sergeant Weiner, who had retired, First Sergeant Johnson looked at me with the kindness of one who has survived much cruelty but will not bestow it.

“You’re a crazy one,” he said. “Someone’s gonna write a book about you. Make you famous. I mean that. Now get the fuck out of my office!”

Restricted to base by Captain Scarlotti, I filed for conscientious objector status. Denied, I wrote my to congressman: “Help! I need to get out of the Army!” When he did not reply, I began the long trek up the Fort Devens chain-of-command. Two months later I reached the top.

By now my hair was shoulder length; my garrison cap kept slipping off my head.

Lieutenant Shaw reluctantly called the General. After a brief exchange, he slammed down the phone. “The General can’t see you today,” he snarled.

“But sir,” I pleaded, “I’m Private Levy. I have an appointment! I’m here to get out of the Army.”

In one cruel motion, Lieutenant Shaw stood and pounded the desk with his fist. “I don’t think you get it, bud. The General will not see you. Now get the fuck out!”

And he really said that.

Three weeks later an officer approached me as I stood in the morning chow line.

“Sign here,” he said, pointing to a large X be neath a dozen paragraphs. “We’ll give you a Bad Conduct Discharge. You’ll be out in a week! Isn’t that what you want?”

neath a dozen paragraphs. “We’ll give you a Bad Conduct Discharge. You’ll be out in a week! Isn’t that what you want?”

A Bad Conduct Discharge, a BCD in Army parlance, is a very bad thing to possess. It identifies the bearer as a person without pride, without honor or scruples, a pariah incapable of serving his country. It also disqualifies the recipient from most state and federal benefits. It is a bright red flag to potential employers. It condemns one to a life of civilian hell.

I looked at the document, then looked at the lieutenant. “No thank you, sir. I’ll take my chances at the Special court-martial.”

The officer was stunned. I was hungry. Drifting from the chow hall, the scent of burnt toast and runny eggs did not decrease my appetite.

One month lat er, a tall, one-eyed colonel threw me out of JAG.

er, a tall, one-eyed colonel threw me out of JAG.

“Sir, you can’t do that. Major Odell has me up for a Special court-martial for refusing to obey orders. I’m here to see Captain Lamarine, my Army lawyer.”

A decorated WW II vet, Colonel Ray Ritter wore a jaunty black eye patch. Cocking his head slightly to the left, he looked me over. “You’re a fucking disgrace to the Army!” he said, and grabbed me by the shoulders and hustled me out of the building. “A fucking disgrace!”

Undeterred, I walked a mile to the Inspector General’s office. A swarthy heavy set man, the general leaned back in his large oak chair, and propped both his legs on a massive wood desk.

A swarthy heavy set man, the general leaned back in his large oak chair, and propped both his legs on a massive wood desk.

“What can I do for you, soldier?”asked IG Schmidt.

“Sir, Colonel Ritter just threw me out of JAG.”

I told IG Schmidt my story while standing at attention in my dress uniform. I had given up on garrison caps, and today wore an Army baseball hat to which I’d painted an officer’s gold oak leaf trim.

The IG looked me over, lit a cigar, and took a long, thoughtful drag. “I’ll look into it,” he said, exhaling a noxious plume.

“Thank you, Sir! Thank you!” I said. I really believed him.

When I returned to company Head Quarters, Captain Scarlotti screamed, “The IG just chewed my ass out! Did you complain about Colonel Ritter? Did you really do that?!?!”

Head Quarters, Captain Scarlotti screamed, “The IG just chewed my ass out! Did you complain about Colonel Ritter? Did you really do that?!?!”

“Sir, you don’t understand. I’m Private Levy. I have a right to legal counsel.”

The captain was furious. “Get the fuck out of my sight!” he yelled at the top of his lungs.“You hear me! Get the fuck out!”

My friends at the Common Sense book store contacted Stan Lapon, a noted civilian attorney. Stan agreed to take my case. Hearing the good news, I went AWOL to Jersey. One night the phone rang. My old man picked it up. “It’s for you,” he said.

“Hello…” I said, tentatively. I wasn’t expecting any calls.

“Doc, it’s Stan. Where are you? Why’d you leave?”

“I’m home, Stan. It’s my birthday. I’m twenty-one.”

“Well, I suppose I have a present for you. Army brass want to give you a Dishonorable Discharge, and three months’ hard labor. But I know someone. They pulled some strings. Plead guilty, serve five days in jail, they’ll give you a General Discharge.”

I looked at my dog. My dog looked at me.

“I don’t know, Stan. What do you think?”

“If I were you, Doc,” he said, “I’d take it.”

“OK, Stan. See you soon.”

We met in an empty JAG office an hour before the proceedings. Looking around, I noticed two stacks of paper on a long metal desk. One pile had copies of my case. The other concerned a General court-martial, the most serious level of military courts, reserved for felony and capital crimes. I read the top page. The charge was statutory rape. The accused was the muscular giant Sergeant Green.

desk. One pile had copies of my case. The other concerned a General court-martial, the most serious level of military courts, reserved for felony and capital crimes. I read the top page. The charge was statutory rape. The accused was the muscular giant Sergeant Green.

After two hours in a tiny courtroom, five officers pronounced the sentence Stan had predicted. Before two imposing MPs lead me away, the court secretary, a shapely brunette, slipped me a tab of Speed.

In the stockade barbershop, one of the MPs said, “Boy, you gonna co-operate or we gonna hold you down?”

The two of them outweighed me by half a ton. “I’ll co-operate,” I said.

My baseball cap was summarily knocked off my head. The prison barber cut my hair to the bone. A photographer snapped my picture with a Polaroid camera. When he wasn’t looking, I pocketed the photo. I gave the Speed to a combat vet who’d slugged an officer, knocking him out.

Five days later I was freed from jail. In the rush to justice, Stan forgot to mention I’d lose all rank and a months pay. Nearly broke, I packed my Army duffle bag, walked past the main gate, said good-bye to Devens, and started hitching to Boston. About noon a red Chevy convertible pulled over. A familiar face leaned out the driver side window.

“Need a lift?” asked the court secretary.

The next morning, after one last fondle and a fond farewell, I began the long trip home.

Addendum

General Albin Felix Irzyk (January 2, 1917 – September 10, 2018) commanded the 8th Tank Battalion of the 4th Armored Division in WWII, the 14th Armored Cavalry Regiment during the Berlin Crisis of 1961, and was Assistant Commander of the 4th Infantry Division in South Vietnam. Devens was his last post. Medic wrote to him in 2009, and apologized for his long ago errant behavior. The general did not recall the events, instead wished me well, and sent two signed copies of his books.