Medic first met Doug Anderson at the William Joiner Center at U Mass Boston in the late 90s or 2000. We have stayed in touch ever since.

Doug served as a Marine corpsman with a rifle company in 1967. After the war he attended the University of Arizona, where he studied acting. He started writing poetry after he moved to Northampton, Massachusetts, and worked with the poet Jack Gilbert. Doug is widely known for his poetry, fiction and memoir. He’s a photographer, too.

Doug’s war poetry collection The Moon Reflected Fire won the Kate Tufts Discovery Award. His other poetry collection is Blues for Unemployed Secret Police. In 2009 he published his memoir, Keep Your Head Down: Vietnam, the Sixties, and a Journey of Self-Discovery. His most recent book of poetry is the extraordinary collection Horse Medicine, published in 2015.

Doug’s war poetry collection The Moon Reflected Fire won the Kate Tufts Discovery Award. His other poetry collection is Blues for Unemployed Secret Police. In 2009 he published his memoir, Keep Your Head Down: Vietnam, the Sixties, and a Journey of Self-Discovery. His most recent book of poetry is the extraordinary collection Horse Medicine, published in 2015.

Doug’s awards include a grant from the Eric Mathieu King Fund of the Academy of American Poets, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, and a Pushcart Prize. He has taught at the University of Connecticut, Eastern Connecticut State University, Emerson College and the William Joiner Center for the Study of War and Its Social Consequences at the University of Massachusetts, Boston.

Medic much appreciates Doug’s friendship and highly recommends all his books. Below are selections from his website.

Vietnam Is Not A War Part I

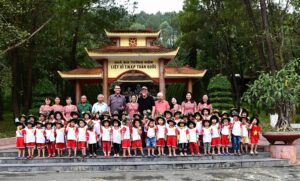

Above photo is at the village of Dong Loc where there is a shrine for ten little girls killed by American bombs. Bruce Weigl is the tall person on the left, I am the tall person on the right.

Above photo is at the village of Dong Loc where there is a shrine for ten little girls killed by American bombs. Bruce Weigl is the tall person on the left, I am the tall person on the right.

Yes, I have a PhD. But my real education began in 1967 as a corpsman with a marine rifle company in I-Corps, the northern most American combat sector in Vietnam. I knew something was wrong with the war the first week I was there and saw an old man beaten by a marine squad leader. The squad leader had become embittered by the war because we were failing, because we’d been told one thing about the war and to our dismay, discovered another. I was horrified by the beating and later I understood the squad leader did not have the intelligence to see what was going on. We were fighting for the Saigon aristocracy but eighty percent of South Vietnam, the mostly rural areas, hated the regime.

The war was structurally impossible. A marine would step on a mine set in a paddy dike. We had observed villagers walking up and down that dike for weeks and NOT stepping on it, therefore they’d been warned by the local Viet Cong cadre. Our solution, again a stupid choice, was to beat the villagers, burn the village down and thus create new enemies. This happened over and over again. Some of us got it: we were fighting for the wrong side. That statement will get me called “traitor” but a goodly number of veterans thought as I did. My platoon commander, a good and kind man, fifty years later said to me, “…and all they wanted was their independence.” It cost thousands of Americans killed and maimed, and four million Vietnamese, half of whom were civilian. We poisoned their land with defoliants and destroyed their agriculture to the extent that this rice-producing country had to import rice to feed itself. How could this have happened? For starters, the politicians who were so enthusiastic about the war understood nothing of the Vietnamese and their history and were deluded by the “domino theory,” a hangover from the red scare of the McCarthy witch hunts. Sadly, most of us who actually did the fighting had never heard of the country and couldn’t find it on a map prior to joining up or being drafted. We were tabula rasa and not real smart.

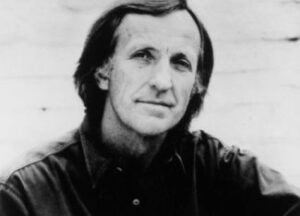

Me in the battalion CP, 1967

Me in the battalion CP, 1967

For thirty years I’ve been an affiliate of the Joiner Institute for the Study of War and Its Social Consequences, a remarkable organization that has brought Americans and their former enemies together through writing. I attended and taught in the summer workshops they offered and through the Institute made trips back to Vietnam and made contact with my Vietnamese creative counterparts. It has been the most rewarding experience of my life.

Hanoi, January 2000

Hanoi, January 2000

When The Old Repeat Their Stories

My father was stationed with a PT boat squadron in the Aleutian Islands during World War II. He’d been drafted at thirty-seven years old (such things happened in that war) and found himself a petty officer in charge of supply. He was gone by the time I was six so I only saw him at intervals as per the custody agreement, particularly later in life. He’d tell the same two stories as if I’d never heard them before. One was losing his shaving kit in the snow and being unable to find it because of a blizzard. The other was the day a survivor of a sunk Japanese mini-sub found an American Navy uniform and slipped into to the line in the base chow hall. He was starving. They captured him immediately, of course. For some reason, those two stories had to be told over and over again.

I’ve never understood the story with the shaving kit. Was it about something lost and irretrievable in his life? Was it about his fear of the danger of blizzards where a man can be as easily lost?

But do understand the story about the captured Japanese. It was about the understanding that the enemy was human and vulnerable, something that violated the mythological version. It created a kind of cognitive dissonance that took time to work through, especially in a time of intense patriotism after Pearl Harbor.

I repeat many of my own stories about Vietnam. Some people have heard them all and humor me. But each time I tell them, sometimes in writing, I am refining the articulation of them so that the words are most transparent and true. Does the memory edit? Not all of it: some memories are burned indelibly into the mind. I remember, for example, each man I couldn’t help. As a platoon corpsman I sometimes tried to keep men alive knowing I couldn’t, so he didn’t have to die alone. It is impossible to save a man who’s been shot through the subclavian artery, in the head, or three times in in the direct center of his chest. Most likely an operating room would not have helped, he bled out so quickly. But I keep telling their story. And I tell stories of the demythologized enemy, the ones we captured, who were scrawny and underfed and sometimes just kids and terrified.

Here is one that will not go away: there was a Viet Cong with a stolen M79, who gave us a lot of grief for a few months. He traveled with two other guys. They specialized in hit and run ambushes. An M79 was a hand-held artillery piece that fired a forty-millimeter grenade. We called this guy the “Mad Seventy-Niner” for the risks he took. We finally killed him just south of Kim Son Mountain. Strangely, we were saddened at his death, even though he’d killed a few of us. He’d become mythological and some little sensor way down in the amygdala saw him as a warrior brother.

Contrary to the fashionable rhetoric, women veterans need to tell these stories too. My friend Anne flew a Kiowa helicopter in Iraq and killed a lot of people. After her deployment she got in her car, disabled the airbags, unhooked her seat belt and drove as fast as she could into a telephone pole. She broke her neck in two places and was in Walter Reed hospital for two years. When I heard her tell her story at the Joiner Institute in the summer of twenty-eighteen, I knew she had to tell it. Narrative is powerful and necessary and like food, we can’t live without it. She is still young and quite lovely and will be telling this story as long as she lives.

These are the indigestible facts of war. They will always be so. This is what the repeated stories are teaching, both for the listener and the teller.

The Myth Is Real

from Horse Medicine

Live Myth

I would believe in the unicorn if it stood heaving and slathered,

snapping flies off its flanks with its tail. It does not smell

of sweat and stable, does not snort at the wolf in the brush

and twitch its ears. I unicorn does not get dirty,

kick up mud when it runs. I know that I would throw

my leg over a bareback horse than I’d step

into the stirrup of a saddled unicorn. For spite, I’d shoot

and slaughter one, roast choice bits over a fire, and hang

its horn from my belt, just to outrage the legions

of tourists of the imagination, the kind who flock

to seances, or invite Rasputin to tea. A unicorn

is impossibly cute, it doesn’t shit or rub its rump against a tree.

But a horse, my God, can swing its neck around at a dog’s yip

and break your jaw, can brain you with a hoof.

It makes the ground shake. Look at him, the black pool

of his eye, muscle rippling along the flanks, and how

he stands, placid, chewing, as the little girl lies on top of him

braiding his mane, whispering, my magic, my magic, my boy.

_________________

Doug Anderson in Revue LISA

(three war poems + short video)

Top photo: horse depicted in Lascaux Cave in the Dordogne, southwestern France, dated to the Upper Palaeolithic period.

Equus Medicamentum

Medic first met Doug Anderson at the William Joiner Center at U Mass Boston in the late 90s or 2000. We have stayed in touch ever since.

Doug served as a Marine corpsman with a rifle company in 1967. After the war he attended the University of Arizona, where he studied acting. He started writing poetry after he moved to Northampton, Massachusetts, and worked with the poet Jack Gilbert. Doug is widely known for his poetry, fiction and memoir. He’s a photographer, too.

Doug’s awards include a grant from the Eric Mathieu King Fund of the Academy of American Poets, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, and a Pushcart Prize. He has taught at the University of Connecticut, Eastern Connecticut State University, Emerson College and the William Joiner Center for the Study of War and Its Social Consequences at the University of Massachusetts, Boston.

Medic much appreciates Doug’s friendship and highly recommends all his books. Below are selections from his website.

Vietnam Is Not A War Part I

Yes, I have a PhD. But my real education began in 1967 as a corpsman with a marine rifle company in I-Corps, the northern most American combat sector in Vietnam. I knew something was wrong with the war the first week I was there and saw an old man beaten by a marine squad leader. The squad leader had become embittered by the war because we were failing, because we’d been told one thing about the war and to our dismay, discovered another. I was horrified by the beating and later I understood the squad leader did not have the intelligence to see what was going on. We were fighting for the Saigon aristocracy but eighty percent of South Vietnam, the mostly rural areas, hated the regime.

The war was structurally impossible. A marine would step on a mine set in a paddy dike. We had observed villagers walking up and down that dike for weeks and NOT stepping on it, therefore they’d been warned by the local Viet Cong cadre. Our solution, again a stupid choice, was to beat the villagers, burn the village down and thus create new enemies. This happened over and over again. Some of us got it: we were fighting for the wrong side. That statement will get me called “traitor” but a goodly number of veterans thought as I did. My platoon commander, a good and kind man, fifty years later said to me, “…and all they wanted was their independence.” It cost thousands of Americans killed and maimed, and four million Vietnamese, half of whom were civilian. We poisoned their land with defoliants and destroyed their agriculture to the extent that this rice-producing country had to import rice to feed itself. How could this have happened? For starters, the politicians who were so enthusiastic about the war understood nothing of the Vietnamese and their history and were deluded by the “domino theory,” a hangover from the red scare of the McCarthy witch hunts. Sadly, most of us who actually did the fighting had never heard of the country and couldn’t find it on a map prior to joining up or being drafted. We were tabula rasa and not real smart.

For thirty years I’ve been an affiliate of the Joiner Institute for the Study of War and Its Social Consequences, a remarkable organization that has brought Americans and their former enemies together through writing. I attended and taught in the summer workshops they offered and through the Institute made trips back to Vietnam and made contact with my Vietnamese creative counterparts. It has been the most rewarding experience of my life.

When The Old Repeat Their Stories

My father was stationed with a PT boat squadron in the Aleutian Islands during World War II. He’d been drafted at thirty-seven years old (such things happened in that war) and found himself a petty officer in charge of supply. He was gone by the time I was six so I only saw him at intervals as per the custody agreement, particularly later in life. He’d tell the same two stories as if I’d never heard them before. One was losing his shaving kit in the snow and being unable to find it because of a blizzard. The other was the day a survivor of a sunk Japanese mini-sub found an American Navy uniform and slipped into to the line in the base chow hall. He was starving. They captured him immediately, of course. For some reason, those two stories had to be told over and over again.

I’ve never understood the story with the shaving kit. Was it about something lost and irretrievable in his life? Was it about his fear of the danger of blizzards where a man can be as easily lost?

But do understand the story about the captured Japanese. It was about the understanding that the enemy was human and vulnerable, something that violated the mythological version. It created a kind of cognitive dissonance that took time to work through, especially in a time of intense patriotism after Pearl Harbor.

I repeat many of my own stories about Vietnam. Some people have heard them all and humor me. But each time I tell them, sometimes in writing, I am refining the articulation of them so that the words are most transparent and true. Does the memory edit? Not all of it: some memories are burned indelibly into the mind. I remember, for example, each man I couldn’t help. As a platoon corpsman I sometimes tried to keep men alive knowing I couldn’t, so he didn’t have to die alone. It is impossible to save a man who’s been shot through the subclavian artery, in the head, or three times in in the direct center of his chest. Most likely an operating room would not have helped, he bled out so quickly. But I keep telling their story. And I tell stories of the demythologized enemy, the ones we captured, who were scrawny and underfed and sometimes just kids and terrified.

Here is one that will not go away: there was a Viet Cong with a stolen M79, who gave us a lot of grief for a few months. He traveled with two other guys. They specialized in hit and run ambushes. An M79 was a hand-held artillery piece that fired a forty-millimeter grenade. We called this guy the “Mad Seventy-Niner” for the risks he took. We finally killed him just south of Kim Son Mountain. Strangely, we were saddened at his death, even though he’d killed a few of us. He’d become mythological and some little sensor way down in the amygdala saw him as a warrior brother.

Contrary to the fashionable rhetoric, women veterans need to tell these stories too. My friend Anne flew a Kiowa helicopter in Iraq and killed a lot of people. After her deployment she got in her car, disabled the airbags, unhooked her seat belt and drove as fast as she could into a telephone pole. She broke her neck in two places and was in Walter Reed hospital for two years. When I heard her tell her story at the Joiner Institute in the summer of twenty-eighteen, I knew she had to tell it. Narrative is powerful and necessary and like food, we can’t live without it. She is still young and quite lovely and will be telling this story as long as she lives.

These are the indigestible facts of war. They will always be so. This is what the repeated stories are teaching, both for the listener and the teller.

The Myth Is Real

from Horse Medicine

Live Myth

I would believe in the unicorn if it stood heaving and slathered,

snapping flies off its flanks with its tail. It does not smell

of sweat and stable, does not snort at the wolf in the brush

and twitch its ears. I unicorn does not get dirty,

kick up mud when it runs. I know that I would throw

my leg over a bareback horse than I’d step

into the stirrup of a saddled unicorn. For spite, I’d shoot

and slaughter one, roast choice bits over a fire, and hang

its horn from my belt, just to outrage the legions

of tourists of the imagination, the kind who flock

to seances, or invite Rasputin to tea. A unicorn

is impossibly cute, it doesn’t shit or rub its rump against a tree.

But a horse, my God, can swing its neck around at a dog’s yip

and break your jaw, can brain you with a hoof.

It makes the ground shake. Look at him, the black pool

of his eye, muscle rippling along the flanks, and how

he stands, placid, chewing, as the little girl lies on top of him

braiding his mane, whispering, my magic, my magic, my boy.

_________________

Doug Anderson in Revue LISA

(three war poems + short video)

Top photo: horse depicted in Lascaux Cave in the Dordogne, southwestern France, dated to the Upper Palaeolithic period.