This article by Medic first appeared in the 25 April 2019 issue of CounterPunch.

Maya Lin’s war monument succeeds by its simplicity. The long tapering wall gradually rising to a delicate peak, falls equally away. Unencumbered, row upon row, by the tens of thousands the mute granite names speak to us, and we are filled with sorrow, rendered still. What more is there to say?

The March/April 2019 issue of VVA’s The Veteran highlights a video project by Westlake High School students in Austin, Texas. As VVA Arts Editor Marc Leepson wrote:

Countless high school English and history teachers around the nation have used The Things They Carried, Tim O’Brien’s masterful 1990 book of linked Vietnam War short stories, in their classes. That’s the case with the English III Advanced Placement class for juniors at Westlake High School in Austin, Texas.

But the English AP teachers at Westlake High have taken teaching that book a step further. As a companion research project, they assign each student to do research on someone whose name is etched on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Then, in the spirit of O’Brien’s book, the students “retell the stories” of the men and women who died in the Vietnam War, as Carolyn Foote, the school’s librarian who helped create the website, put it.

The students, that is, create video presentations, complete with music, images, photographs, official documents, and the memories of families and friends whom they interview. Since 2007 those video memorials have been posted on the school’s website on a page called the Virtual Vietnam Memorial. More than 1,800 student video memorials have been posted on the page.

Students create their video memorializing projects “using a variety of software to tell the story of a soldier’s life and death…”

Leepson is a Vietnam vet, a noted journalist, historian, the accomplished author of nine books. His work has been widely published, including in The New York Times, The Washington Post. He has been interviewed many times on radio and TV. Over the years Leepson and I have traded friendly emails. But I am perplexed by his generous review of the Virtual Vietnam Project.

I watched a half-dozen of the video clips. Each one followed a formula: sweet or sad or rousing music played over a succession of pleasant, captioned images of the deceased, who had put himself in harms way, died for his country, perished heroically.

This uncritical sentimentalizing makes me sad for what is lost to fantasy, idealization, the received myths of patriotism. I’m not alone in my response. Several combat vet friends expressed similar thoughts. The students’ efforts were well-intentioned, my friends said, but they just don’t get it. Hearts and flowers may comfort the living–but they also bury the truth of war, and make us complicit in its sequels.

Several of the clips I viewed were of KIAs in the 101st Airborne Division. How many of those men were in Tiger Force, the notorious 101st Airborne unit which from September 1967 to February 1968 committed hundreds of atrocities? A lengthy Army investigation was covered up, but in 2003 the Toledo Blade ran a series of exposes. The New York Times and other national papers also reported the story. For a time readers were upset by the ferocity of war crimes revealed, the absence of punishment meted out.

Several of the clips I viewed were of KIAs in the 101st Airborne Division. How many of those men were in Tiger Force, the notorious 101st Airborne unit which from September 1967 to February 1968 committed hundreds of atrocities? A lengthy Army investigation was covered up, but in 2003 the Toledo Blade ran a series of exposes. The New York Times and other national papers also reported the story. For a time readers were upset by the ferocity of war crimes revealed, the absence of punishment meted out.

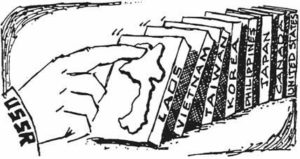

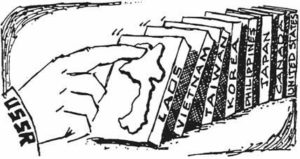

As portrayed by Nick Turse in Kill Anything That Moves, war crimes committed by US troops were not isolated incidents. Too often they were unspoken policy.

The Texas students seem not to question the complexity of America’s war in Vietnam, or the varieties of death to be met there. One by one the simple, well-made videos invoke the soldiers’ unshakeable duty to honor and country—his protecting–by heroic sacrifice, our jeopardized freedom—a long and well-debunked political myth.

And what if the soldier were killed by friendly fire? Or died from tropical disease? Or was deliberately killed by another American? Two reasonable estimates: twelve percent of US forces in Vietnam participated in direct combat. Fifteen percent of those men were killed or wounded by friendly fire, non-hostile incidents or other causes.

A few run-of-the-mill examples:

● I didn’t know Bruce Goodsell but we both served in Delta 1/7 First Cavalry in 1970. One night Bruce and two men sat in a fire base bunker. The fellow sitting opposite Bruce, having taken apart his rifle, cleaned and reassembled it, slapped in a  magazine. He was tired, not thinking clearly when he fired the weapon on full automatic, hitting Bruce multiple times, severing his femoral artery. Bruce bled out in a matter of minutes. You can be sure that a lifetime of guilt followed.

magazine. He was tired, not thinking clearly when he fired the weapon on full automatic, hitting Bruce multiple times, severing his femoral artery. Bruce bled out in a matter of minutes. You can be sure that a lifetime of guilt followed.

● The transfer from the First Division had fiery red hair; we called him Red. One afternoon I stayed back as my squad went on patrol. When they radioed for help–ambush, they said, three of us ran through the jungle, only to find Red shot six times in the arms, legs, belly. My squad was silent as I patched him up. Twenty-five years later I learned that twice before Red had refused to go forward in combat, so this time they shot him.

● On the twenty bird assault into Cambodia every man in Delta thought he would die. But nothing happened; we spent the day digging in. The next morning an Alpha company patrol mistook a Delta company patrol for the enemy. With murderous fire they raked bullets over each other. It’s called an All-American fire fight. No one died, but Leon Gunter was shot through the hand. “Just a flesh wound,” I said, patching him up.

● One morning machine gunner Ray Williams kicked a discarded hand flare that launched into his face, split his nose apart, soared into the sky, hissed and swayed and fluttered down. He was medivaced, but two weeks later, returned.

● Bill Williams, a college grad from Hailey, Idaho, twenty-six years old, had been wounded and assigned to a rear job typing casualty reports. When he refused to slim our losses, to gin the enemy’s, the brass sent him back to the field. Reconning an ambush, Bill was shot in the head, lived a few days, then died. From the jungle we wrote to his wife. A few weeks later, overwhelmed by her desperate response, I could not reply. In 1998 I found her, and Bill’s two brothers. From his last letters home they thought Bill was safe. The Army stone-walled them for thirty years.

● Someone spotted dinks in a gully. The lieutenant sent the machine gun  team up the hill. Loach came in, Light Observation Chopper, opened up on Johnny B with 7.62 slugs, then walked the bullets down the hill. “Doc, get up there,” the lieutenant shouted. I ran up and straddled Johnny B, sitting on his belly. His legs were mangled, his artery was busted, and Johnny B was screaming. A Cobra gun ship power-dived in, unleashing mini-guns, forty mike-mike grenades, its rockets shrieking overhead like white thread gone crazy. I patched Johnny up.“Stop shaking,” I yelled. “C’mon, Johnny B, we’re gonna pray to fucking Jesus.” We dragged Johnny down to a crater, hooked the D ring wench to the medevac’s canvas stretcher, tucked him in good and tight. As they hoisted him up, over the engines’ roar I shouted, “Everyone loves you, Johnny B.” Later we heard that he walked with a cane. That he planned to get married.

team up the hill. Loach came in, Light Observation Chopper, opened up on Johnny B with 7.62 slugs, then walked the bullets down the hill. “Doc, get up there,” the lieutenant shouted. I ran up and straddled Johnny B, sitting on his belly. His legs were mangled, his artery was busted, and Johnny B was screaming. A Cobra gun ship power-dived in, unleashing mini-guns, forty mike-mike grenades, its rockets shrieking overhead like white thread gone crazy. I patched Johnny up.“Stop shaking,” I yelled. “C’mon, Johnny B, we’re gonna pray to fucking Jesus.” We dragged Johnny down to a crater, hooked the D ring wench to the medevac’s canvas stretcher, tucked him in good and tight. As they hoisted him up, over the engines’ roar I shouted, “Everyone loves you, Johnny B.” Later we heard that he walked with a cane. That he planned to get married.

● After the ambush the lieutenant yelled, “Chieu hoi!” but the wounded enemy did not surrender, instead lifted his AK, and point blank the lieutenant shot him, as did the machine gun team and twenty grunts behind him. When the smoke cleared the man had no head. Later the lieutenant asked, “You gonna put me in for a Purple Heart, Doc?” and showed me his chipped tooth. “No way, lieutenant. You didn’t get shot. You didn’t get hit. It’s just skull fragments from the dead dink.”

● A friend from Bravo 1/7 Cav relates, “There was a fire fight where we captured a man dressed in black pants and shirt. He was old, in pain, full of fear. I watched X push and grind his M16 into the old man. I remember telling X to stop it. He gave me this psychotic grin, like fuck you, which really pissed me off. The POW was just a weak old man. Later they air-lifted him out, on a rope, dangling, so he scruffed through the tree tops. That made me sick. Vietnam made us do things we never thought we were capable of. Like most of you guys, I have memories I’d wish were not true.”

● My friend Mike Hudzinski tells of the horror of surviving a sapper attack  on LZ Ranch in Cambodia, where the men near him were cut in half or blasted to bits. I was on that base that night, luckily 60 or so yards from where the enemy suicide troops crawled in and began their attack. They were ruthless, murdering GIs with hand grenades, explosive charges, automatic weapons fire. My friend Carl Lee played dead as an enemy soldier walked past, then he rose up and killed him. Minutes later he held Mike Dawson in his arms as Mike bled to death. Five Americans died that night. Twenty-six were wounded. Twelve NVA were killed by automatic weapons or cannons fired directly into the wood line. At dawn, Mike Wilson and I tossed their bullet-riddled bodies into a crater, covered them with lime.

on LZ Ranch in Cambodia, where the men near him were cut in half or blasted to bits. I was on that base that night, luckily 60 or so yards from where the enemy suicide troops crawled in and began their attack. They were ruthless, murdering GIs with hand grenades, explosive charges, automatic weapons fire. My friend Carl Lee played dead as an enemy soldier walked past, then he rose up and killed him. Minutes later he held Mike Dawson in his arms as Mike bled to death. Five Americans died that night. Twenty-six were wounded. Twelve NVA were killed by automatic weapons or cannons fired directly into the wood line. At dawn, Mike Wilson and I tossed their bullet-riddled bodies into a crater, covered them with lime.

And what of men unsuited for combat? A criminal record, low IQ, or various physical conditions normally disqualified a man from military service. When Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara dropped induction standards, thousands of unsuitable men, known as MacNamara’s Morons, were needlessly killed or wounded. The late Vietnam veteran and journalist Hamilton Gregory has written a best-selling book on this subject.

I’m happy to say that a Westlake High School teacher Kristy Robins, in an eloquent and thoughtful email, informed me that The Things They Carry highlights the mental and physical struggles of battle, the futility of the war, the difficulty of returning home, the burden of memory. She noted that a panel of Vietnam veterans headed by a Marine sniper speak to her classes about their experiences at war and their struggles upon returning home.

Ms. Robins also emphasized that during their research, the students often arrived at complex questions and facts which were difficult to digest.

They sympathize with the young men who enlisted without knowing what they were getting into. They are horrified to know that young people just a year or two older than them were drafted and forced to give up their plans for the future. They are saddened by the loss of lives, both American and Vietnamese. They are outraged by the atrocities committed by American soldiers. They are puzzled as to why the US military forces were there in the first place. Those aspects don’t make it into the memorial videos, but when you consider the audience and purpose of these memorials, I hope you can understand why.

It is true that my students probably “just don’t get it.” I think that they even understand that they can’t really “get it” without having been there. Still, it is their intention, and ours as their teachers, to honor and remember the individuals who didn’t make it back from the war, not to celebrate the war itself.

Fair enough. But the savagery of combat remains unknown to most Americans. Imagining those casualties, honoring them without question, seems misguided. The annual parades, fervent wreath-laying, solemn speeches–all serve to mute war’s brutal squalor. Do high school teachers really need to perpetuate the Old Lie revealed by Wilfred Owen’s Dulce Et Decorum Est?

It is true that Tim O’Brien tells a good war tale. It is good that Marine sniper Don Dorsey speaks to Westlake High School students about war and its aftermath. But why not dismantle the scaffold of myths that caused the senseless deaths of men in battle? Why not tell of citizens and soldiers who protested Vietnam and helped to end it?

It is true that Tim O’Brien tells a good war tale. It is good that Marine sniper Don Dorsey speaks to Westlake High School students about war and its aftermath. But why not dismantle the scaffold of myths that caused the senseless deaths of men in battle? Why not tell of citizens and soldiers who protested Vietnam and helped to end it?

Tell of the Berrigan boys, their burning cards, the Catonsville Nine. Tell of Hugh Thompson’s maneuver to end My Lai. Tell how Colburn, Ridenhour, Hersh brought the massacre to light. Tell of stalwart war correspondents Gloria Emerson and Wilfred Burchett. Tell of the anti-war speeches by Muhammad Ali, Benjamin Spock, Martin Luther King. Tell of the work of Howard Zinn. Tell how Jeff Sharlet lead GIs against the war. Tell what changed Dan Ellsberg’s intellectual heart. Tell of Ho Chi Minh working for the OSS. Tell of Thích Quảng Đức, the Buddhist monk who set himself on fire. Tell of the US deporting anti-war student Nguyen Thai Binh. Tell of the damaging intel reports of OSS Lieutenant A. Peter Dewey, KIA, Vietnam, 1945. Tell of the unflinching gaze of Schoendoerffer’s Anderson Platoon. Tell of the CIA’s secret report on nuking Vietnam. A few good places to start, don’t you think?

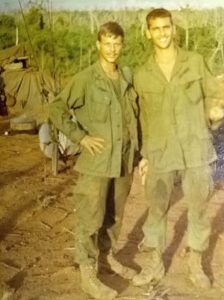

Twenty years ago at a writer’s workshop in Boston I met the two-tour, heavy-combat Vietnam vet Ted Sexauer. At the time I did not appreciate the severity of his sorrow. An excerpt from his bio in the poetry anthology Veterans of War, Veterans of Peace, edited by Maxine Hong Kingston, is instructive:

I went to war to fight against war. I was already in the Army, having enlisted in the face of the draft, before I came to understand the moral ugliness of the war in Viet Nam. I felt betrayed. As a citizen of the offending nation, I felt I had an obligation to try to set right the wrong. I did what I’d set out to do, but it cost a great deal. The moral clarity I’d acted on became clouded and confused. I saved some lives, and I helped the army machine do its work. I was an accomplice to murder. I did a lot of medcaps (village clinics), and that was good, and the army used them as propaganda. Doing the right thing did not make me lighter—it gave me nightmares; it confused the hell out of me.

I went to war to fight against war. I do not recommend that course. To young people, I say: Work for peace before you get into a compromised position. Do not stand up for empire. There is humanity inside the machine, but any way you cut it, the military is about killing.

Ignorance, willful and unintended, about the war and its context has plagued the US now for more than sixty years–it’s time for this generation of teachers and their students to end it.

All My Vexes Are In Texas

This article by Medic first appeared in the 25 April 2019 issue of CounterPunch.

Maya Lin’s war monument succeeds by its simplicity. The long tapering wall gradually rising to a delicate peak, falls equally away. Unencumbered, row upon row, by the tens of thousands the mute granite names speak to us, and we are filled with sorrow, rendered still. What more is there to say?

The March/April 2019 issue of VVA’s The Veteran highlights a video project by Westlake High School students in Austin, Texas. As VVA Arts Editor Marc Leepson wrote:

Countless high school English and history teachers around the nation have used The Things They Carried, Tim O’Brien’s masterful 1990 book of linked Vietnam War short stories, in their classes. That’s the case with the English III Advanced Placement class for juniors at Westlake High School in Austin, Texas.

But the English AP teachers at Westlake High have taken teaching that book a step further. As a companion research project, they assign each student to do research on someone whose name is etched on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Then, in the spirit of O’Brien’s book, the students “retell the stories” of the men and women who died in the Vietnam War, as Carolyn Foote, the school’s librarian who helped create the website, put it.

The students, that is, create video presentations, complete with music, images, photographs, official documents, and the memories of families and friends whom they interview. Since 2007 those video memorials have been posted on the school’s website on a page called the Virtual Vietnam Memorial. More than 1,800 student video memorials have been posted on the page.

Students create their video memorializing projects “using a variety of software to tell the story of a soldier’s life and death…”

Leepson is a Vietnam vet, a noted journalist, historian, the accomplished author of nine books. His work has been widely published, including in The New York Times, The Washington Post. He has been interviewed many times on radio and TV. Over the years Leepson and I have traded friendly emails. But I am perplexed by his generous review of the Virtual Vietnam Project.

I watched a half-dozen of the video clips. Each one followed a formula: sweet or sad or rousing music played over a succession of pleasant, captioned images of the deceased, who had put himself in harms way, died for his country, perished heroically.

This uncritical sentimentalizing makes me sad for what is lost to fantasy, idealization, the received myths of patriotism. I’m not alone in my response. Several combat vet friends expressed similar thoughts. The students’ efforts were well-intentioned, my friends said, but they just don’t get it. Hearts and flowers may comfort the living–but they also bury the truth of war, and make us complicit in its sequels.

As portrayed by Nick Turse in Kill Anything That Moves, war crimes committed by US troops were not isolated incidents. Too often they were unspoken policy.

The Texas students seem not to question the complexity of America’s war in Vietnam, or the varieties of death to be met there. One by one the simple, well-made videos invoke the soldiers’ unshakeable duty to honor and country—his protecting–by heroic sacrifice, our jeopardized freedom—a long and well-debunked political myth.

And what if the soldier were killed by friendly fire? Or died from tropical disease? Or was deliberately killed by another American? Two reasonable estimates: twelve percent of US forces in Vietnam participated in direct combat. Fifteen percent of those men were killed or wounded by friendly fire, non-hostile incidents or other causes.

A few run-of-the-mill examples:

● I didn’t know Bruce Goodsell but we both served in Delta 1/7 First Cavalry in 1970. One night Bruce and two men sat in a fire base bunker. The fellow sitting opposite Bruce, having taken apart his rifle, cleaned and reassembled it, slapped in a magazine. He was tired, not thinking clearly when he fired the weapon on full automatic, hitting Bruce multiple times, severing his femoral artery. Bruce bled out in a matter of minutes. You can be sure that a lifetime of guilt followed.

magazine. He was tired, not thinking clearly when he fired the weapon on full automatic, hitting Bruce multiple times, severing his femoral artery. Bruce bled out in a matter of minutes. You can be sure that a lifetime of guilt followed.

● The transfer from the First Division had fiery red hair; we called him Red. One afternoon I stayed back as my squad went on patrol. When they radioed for help–ambush, they said, three of us ran through the jungle, only to find Red shot six times in the arms, legs, belly. My squad was silent as I patched him up. Twenty-five years later I learned that twice before Red had refused to go forward in combat, so this time they shot him.

● On the twenty bird assault into Cambodia every man in Delta thought he would die. But nothing happened; we spent the day digging in. The next morning an Alpha company patrol mistook a Delta company patrol for the enemy. With murderous fire they raked bullets over each other. It’s called an All-American fire fight. No one died, but Leon Gunter was shot through the hand. “Just a flesh wound,” I said, patching him up.

● One morning machine gunner Ray Williams kicked a discarded hand flare that launched into his face, split his nose apart, soared into the sky, hissed and swayed and fluttered down. He was medivaced, but two weeks later, returned.

● Bill Williams, a college grad from Hailey, Idaho, twenty-six years old, had been wounded and assigned to a rear job typing casualty reports. When he refused to slim our losses, to gin the enemy’s, the brass sent him back to the field. Reconning an ambush, Bill was shot in the head, lived a few days, then died. From the jungle we wrote to his wife. A few weeks later, overwhelmed by her desperate response, I could not reply. In 1998 I found her, and Bill’s two brothers. From his last letters home they thought Bill was safe. The Army stone-walled them for thirty years.

● Someone spotted dinks in a gully. The lieutenant sent the machine gun team up the hill. Loach came in, Light Observation Chopper, opened up on Johnny B with 7.62 slugs, then walked the bullets down the hill. “Doc, get up there,” the lieutenant shouted. I ran up and straddled Johnny B, sitting on his belly. His legs were mangled, his artery was busted, and Johnny B was screaming. A Cobra gun ship power-dived in, unleashing mini-guns, forty mike-mike grenades, its rockets shrieking overhead like white thread gone crazy. I patched Johnny up.“Stop shaking,” I yelled. “C’mon, Johnny B, we’re gonna pray to fucking Jesus.” We dragged Johnny down to a crater, hooked the D ring wench to the medevac’s canvas stretcher, tucked him in good and tight. As they hoisted him up, over the engines’ roar I shouted, “Everyone loves you, Johnny B.” Later we heard that he walked with a cane. That he planned to get married.

team up the hill. Loach came in, Light Observation Chopper, opened up on Johnny B with 7.62 slugs, then walked the bullets down the hill. “Doc, get up there,” the lieutenant shouted. I ran up and straddled Johnny B, sitting on his belly. His legs were mangled, his artery was busted, and Johnny B was screaming. A Cobra gun ship power-dived in, unleashing mini-guns, forty mike-mike grenades, its rockets shrieking overhead like white thread gone crazy. I patched Johnny up.“Stop shaking,” I yelled. “C’mon, Johnny B, we’re gonna pray to fucking Jesus.” We dragged Johnny down to a crater, hooked the D ring wench to the medevac’s canvas stretcher, tucked him in good and tight. As they hoisted him up, over the engines’ roar I shouted, “Everyone loves you, Johnny B.” Later we heard that he walked with a cane. That he planned to get married.

● After the ambush the lieutenant yelled, “Chieu hoi!” but the wounded enemy did not surrender, instead lifted his AK, and point blank the lieutenant shot him, as did the machine gun team and twenty grunts behind him. When the smoke cleared the man had no head. Later the lieutenant asked, “You gonna put me in for a Purple Heart, Doc?” and showed me his chipped tooth. “No way, lieutenant. You didn’t get shot. You didn’t get hit. It’s just skull fragments from the dead dink.”

● A friend from Bravo 1/7 Cav relates, “There was a fire fight where we captured a man dressed in black pants and shirt. He was old, in pain, full of fear. I watched X push and grind his M16 into the old man. I remember telling X to stop it. He gave me this psychotic grin, like fuck you, which really pissed me off. The POW was just a weak old man. Later they air-lifted him out, on a rope, dangling, so he scruffed through the tree tops. That made me sick. Vietnam made us do things we never thought we were capable of. Like most of you guys, I have memories I’d wish were not true.”

● My friend Mike Hudzinski tells of the horror of surviving a sapper attack on LZ Ranch in Cambodia, where the men near him were cut in half or blasted to bits. I was on that base that night, luckily 60 or so yards from where the enemy suicide troops crawled in and began their attack. They were ruthless, murdering GIs with hand grenades, explosive charges, automatic weapons fire. My friend Carl Lee played dead as an enemy soldier walked past, then he rose up and killed him. Minutes later he held Mike Dawson in his arms as Mike bled to death. Five Americans died that night. Twenty-six were wounded. Twelve NVA were killed by automatic weapons or cannons fired directly into the wood line. At dawn, Mike Wilson and I tossed their bullet-riddled bodies into a crater, covered them with lime.

on LZ Ranch in Cambodia, where the men near him were cut in half or blasted to bits. I was on that base that night, luckily 60 or so yards from where the enemy suicide troops crawled in and began their attack. They were ruthless, murdering GIs with hand grenades, explosive charges, automatic weapons fire. My friend Carl Lee played dead as an enemy soldier walked past, then he rose up and killed him. Minutes later he held Mike Dawson in his arms as Mike bled to death. Five Americans died that night. Twenty-six were wounded. Twelve NVA were killed by automatic weapons or cannons fired directly into the wood line. At dawn, Mike Wilson and I tossed their bullet-riddled bodies into a crater, covered them with lime.

And what of men unsuited for combat? A criminal record, low IQ, or various physical conditions normally disqualified a man from military service. When Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara dropped induction standards, thousands of unsuitable men, known as MacNamara’s Morons, were needlessly killed or wounded. The late Vietnam veteran and journalist Hamilton Gregory has written a best-selling book on this subject.

I’m happy to say that a Westlake High School teacher Kristy Robins, in an eloquent and thoughtful email, informed me that The Things They Carry highlights the mental and physical struggles of battle, the futility of the war, the difficulty of returning home, the burden of memory. She noted that a panel of Vietnam veterans headed by a Marine sniper speak to her classes about their experiences at war and their struggles upon returning home.

Ms. Robins also emphasized that during their research, the students often arrived at complex questions and facts which were difficult to digest.

They sympathize with the young men who enlisted without knowing what they were getting into. They are horrified to know that young people just a year or two older than them were drafted and forced to give up their plans for the future. They are saddened by the loss of lives, both American and Vietnamese. They are outraged by the atrocities committed by American soldiers. They are puzzled as to why the US military forces were there in the first place. Those aspects don’t make it into the memorial videos, but when you consider the audience and purpose of these memorials, I hope you can understand why.

It is true that my students probably “just don’t get it.” I think that they even understand that they can’t really “get it” without having been there. Still, it is their intention, and ours as their teachers, to honor and remember the individuals who didn’t make it back from the war, not to celebrate the war itself.

Fair enough. But the savagery of combat remains unknown to most Americans. Imagining those casualties, honoring them without question, seems misguided. The annual parades, fervent wreath-laying, solemn speeches–all serve to mute war’s brutal squalor. Do high school teachers really need to perpetuate the Old Lie revealed by Wilfred Owen’s Dulce Et Decorum Est?

Tell of the Berrigan boys, their burning cards, the Catonsville Nine. Tell of Hugh Thompson’s maneuver to end My Lai. Tell how Colburn, Ridenhour, Hersh brought the massacre to light. Tell of stalwart war correspondents Gloria Emerson and Wilfred Burchett. Tell of the anti-war speeches by Muhammad Ali, Benjamin Spock, Martin Luther King. Tell of the work of Howard Zinn. Tell how Jeff Sharlet lead GIs against the war. Tell what changed Dan Ellsberg’s intellectual heart. Tell of Ho Chi Minh working for the OSS. Tell of Thích Quảng Đức, the Buddhist monk who set himself on fire. Tell of the US deporting anti-war student Nguyen Thai Binh. Tell of the damaging intel reports of OSS Lieutenant A. Peter Dewey, KIA, Vietnam, 1945. Tell of the unflinching gaze of Schoendoerffer’s Anderson Platoon. Tell of the CIA’s secret report on nuking Vietnam. A few good places to start, don’t you think?

Twenty years ago at a writer’s workshop in Boston I met the two-tour, heavy-combat Vietnam vet Ted Sexauer. At the time I did not appreciate the severity of his sorrow. An excerpt from his bio in the poetry anthology Veterans of War, Veterans of Peace, edited by Maxine Hong Kingston, is instructive:

I went to war to fight against war. I was already in the Army, having enlisted in the face of the draft, before I came to understand the moral ugliness of the war in Viet Nam. I felt betrayed. As a citizen of the offending nation, I felt I had an obligation to try to set right the wrong. I did what I’d set out to do, but it cost a great deal. The moral clarity I’d acted on became clouded and confused. I saved some lives, and I helped the army machine do its work. I was an accomplice to murder. I did a lot of medcaps (village clinics), and that was good, and the army used them as propaganda. Doing the right thing did not make me lighter—it gave me nightmares; it confused the hell out of me.

I went to war to fight against war. I do not recommend that course. To young people, I say: Work for peace before you get into a compromised position. Do not stand up for empire. There is humanity inside the machine, but any way you cut it, the military is about killing.

Ignorance, willful and unintended, about the war and its context has plagued the US now for more than sixty years–it’s time for this generation of teachers and their students to end it.