When first published on Medic in the Green Time the name of the Salem, Mass veterans agent was fictionalized. On 11 November 2021 the article appeared in CounterPunch, where Medic named the veteran’s agent. Subsequently, the Secretary of Veterans Services for Massachusetts and the veterans agent expressed their strong disapproval of the story. See addendum.

Vicomte de Valvert: Monsieur, your nose… your nose is rather large.

Cyrano de Bergerac: Rather?

Vicomte de Valvert: Oh, well…

Cyrano de Bergerac: Is that all?

Vicomte de Valvert: Well of course…

Cyrano de Bergerac: Oh, no, young sir. You are too simple. Why, you might have said a great many things. Why waste your opportunity?

Edmond Rostand

Cyrano de Bergerac, Scene 1, Act 1

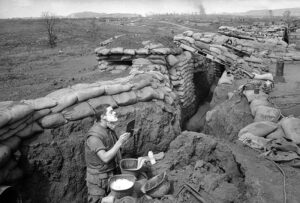

Not long ago my neighbor Carol suggested I apply to live at a soldier’s home. She knew I’d done a tour in Vietnam as an infantry medic in 1970.

“My father lives there,” she said. “The food is great. The rent is cheap. They take care of everything.”

“My father lives there,” she said. “The food is great. The rent is cheap. They take care of everything.”

I’m on two housing lists but figured why not? I filled out an application; two months later I had an interview at the Chelsea Soldiers’ Home in Boston. On a chilly New England morning veteran’s agent Kim Emerling and I visited the Home. We arrived early and waited in the car. I would have to take a rapid Covid test to enter the three-story building. After a time, a nurse I’ll call Hank emerged from the blue canopied front door.

A tall, muscular man, he carried a basket filled with medical supplies suited to his present task. Ambling toward us, he stopped abruptly to chat with an elderly female veteran. A few minutes later, he leisurely conversed with the driver of a delivery van. During this time Kim growled words which I will not relate. Finally, as if in a dream—mine or his I could not tell—Hank sauntered toward us. I had the curious impression that here was a man bereft of intellect and medicinal insight.

Leaning into the passenger side window, Hank confided that to properly  administer the rapid antigen test I would first have to blow my nose. My neighbor had warned me of this. I told Hank “No,” I could not do that.

administer the rapid antigen test I would first have to blow my nose. My neighbor had warned me of this. I told Hank “No,” I could not do that.

“Is that a medical condition?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “My nose will bleed if I blow it.”

Nose bleeds were the scourge of my childhood and continue, though less frequently, to this day. I’ve had my nose cauterized several times. Hank returned to the building to check with administrative staff. He came back a few minutes later.

“You can’t enter without taking the test.”

I had a bad feeling. Something told me things would not go right. What to do? I did not blow my nose, but reluctantly allowed Hank to swab my nasal passages.

“I’ll try to get a good sample,” he said, and swabbed diligently three times inside each nostril.

As Hank inserted the swab into a container, loud and clear I said, “I’m bleeding.” Hank looked up from his task. He saw the blood on my face.

“You weren’t kidding,” he said.

Undeterred—or, inspired by the sight of re liquid dripping down an old man’s chin—Hank said he would return the swab sample to the building, wait fifteen minutes for the results, then revisit me to administer a PCR swab test, also required—with results in five to seven days.

While we waited, I contemplated my reflection in the visor mirror. A shiny red rivulet coursed from my nose, over my lips, down my chin, and splashed onto my tan Carhartt jacket, branding it with a distinctive red scar. Kim handed me tissues to stanch the bleeding. I pushed the tissue into my nose. This is absurd, I thought. Do I really need to be twice bloodied by a civil servant incapable of mercy? It is one thing to knowingly cause medical injury without thought of consequence. But to even consider inflicting soft tissue insult a second time is cause for alarm.

While we waited, I contemplated my reflection in the visor mirror. A shiny red rivulet coursed from my nose, over my lips, down my chin, and splashed onto my tan Carhartt jacket, branding it with a distinctive red scar. Kim handed me tissues to stanch the bleeding. I pushed the tissue into my nose. This is absurd, I thought. Do I really need to be twice bloodied by a civil servant incapable of mercy? It is one thing to knowingly cause medical injury without thought of consequence. But to even consider inflicting soft tissue insult a second time is cause for alarm.

When Hank returned I announced, “Never mind. I’ve lost enough blood for today!”

Almost cheerfully, Hank said he would talk with admin to see if I could enter the building without the second test. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.

Instead, I imagined calling in heavy artillery from LZ Ranch—a remote firebase in Cambodia which I’d had the pleasure to occupy while it was overrun—and moments later I swore I heard the welcoming sound of incoming 155 shells  whistling overhead. In the eye of my mind I witnessed their fiery crrrumpBANGs exploding upon the building’s immense front door. Seconds later I fancied power diving Cobra gun ships unleashing salvos of white-tailed rockets, 40 mike-mike grenades, and withering miniguns into the black tarred roof. I imagined that inside the home all was havoc. I was elated. Please note that I am not discounting the proven efficacy of the B40 RPG, the primitive but deadly Chicom grenade, or the wicked tripod-mounted 30. caliber machine gun. In my reverie only American weapons was employed.

whistling overhead. In the eye of my mind I witnessed their fiery crrrumpBANGs exploding upon the building’s immense front door. Seconds later I fancied power diving Cobra gun ships unleashing salvos of white-tailed rockets, 40 mike-mike grenades, and withering miniguns into the black tarred roof. I imagined that inside the home all was havoc. I was elated. Please note that I am not discounting the proven efficacy of the B40 RPG, the primitive but deadly Chicom grenade, or the wicked tripod-mounted 30. caliber machine gun. In my reverie only American weapons was employed.

When Hank returned he asked that I call admin. I did so. A woman I’ll call Linda stated I could not enter the building without taking the slow result PCR test. Three times, quite clearly, I half-shouted, “Miss, I’m bleeding as we speak!” Three times Admin Linda ignored my distress. Anger. I had murderous anger and wilting anxiety, but somehow asked Linda if the interview could be done by phone.

“Absolutely not,” she declared.

I inquired about rescheduling the war. Pardon me. The visit. Linda asked me to wait in the car while she consulted a doctor.

“You can’t enter the building without the PCR test,” she sternly repeated. “But don’t worry. The swab will not enter your brain.”

Perhaps not my brain—but what about hers? I called in another air strike. Four squadrons of B52s roared overhead. When the trembling earth quieted and the thick smoke cleared, alone amongst the ruins, there stood Linda, grinning triumphantly.

Perhaps not my brain—but what about hers? I called in another air strike. Four squadrons of B52s roared overhead. When the trembling earth quieted and the thick smoke cleared, alone amongst the ruins, there stood Linda, grinning triumphantly.

At this point, bleeding and agitated, somehow, in a civil tone I terminated the visit. Kim, at the wheel all this time, handed me a fresh set of tissues, then us drove back to home sweet Salem.

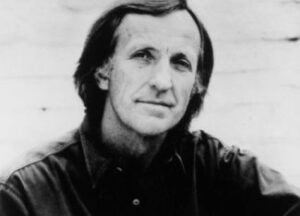

Kim, a Special Forces command sergeant major who’d seen his share of combat, takes all things in stride. “It’ll work out,” he said. “You still bleeding?”

Two weeks later, for reason’s known only to itself, the Chelsea Soldiers’ Home called and asked if I wanted to reschedule my visit.

“Of course, you’ll have to take the Covid test,” said the polite female caller. “Ahhhhh…No,” I said.

I noted that complaints had been filed with the state Massachusetts Secretary of Veterans Affairs. With the VA Inspector General.

There came a gulping noise. “Oh,” she said.

“Oh,” I echoed, and politely hung up.

A month later I received a letter from the VA IG. My complaint had been forwarded to the Massachusetts Secretary of Veterans Affairs.

A full two months after the initial nasal attack I received a phone call from the director of the Chelsea Soldiers’ Home, the amiable Eric Johnson. Our conversation was cordial. I emphasized the beguiling way my conspicuous bleeding was ignored—by Hank, the Nurse and Admin Linda. The director offered to consider my suggestions on how to improve patient care in anomalous circumstances. Several times he encouraged me to reapply to the Soldiers’ Home.

Politely, I told him, “That’s not gonna happen. But thank you for calling.”

_____________

Addendum

After publication of this story on CounterPunch Medic received an email from retired Special Forces Command Sergeant Major and Salem veteran’s agent Kim Emerling. The story, he noted, had been forwarded to him by Cheryl Poppe, Secretary, Massachusetts Department of Veterans’ Services. He found the article embarrassing. The events related did not represent all the good work he had done with veterans. Medic replied:

“Compared to my website, CounterPunch has a large readership and 11 November gave me the opportunity to tell a true postwar story that would resonate with vets as well as non vet readers. Since the official VA response to what happened to me was late and minimal, putting the story on CounterPunch gave me the chance to vent my anger, though offset with humor.

“I figured it was best not to name the nurse, the admin woman, or Cheryl Poppe and Eric Johnson [the Chelsea Soldier Home Superintendent], but what I wrote about you was favorable, so I felt there was no harm changing Barry Carlson to Kim.

“I regret not telling you that I would use your name, though what I wrote was favorable to you. I’m sorry if the fallout from my CounterPunch article has affected you, but in fact you did nothing wrong. Throughout the ordeal, an inexcusable sequence of events which led to me sitting in your car bleeding, and ignored by CSH staff, you kept me calm. You stayed in control. How is that embarrassing to you?

“Afterward, on my behalf, you contacted Cheryl, who for weeks did not respond. Cheryl Poppe, Eric Johnson, Peter the nurse, the admin woman I spoke to on the phone, all deserve embarrassment–if not more–for what happened to me. None of which reflects on you, an eye witness to those events, or your good work with veterans.

“In summary, I see it this way: advised of an unnecessary injury inflicted on me by CSH medical staff, admin at Chelsea Soldiers’ Home failed to assist a bleeding, 100% disabled, highly decorated combat veteran, who later required specialist medical attention to address those injuries. During that time, as I continued to bleed and experience severe war related anxiety, you acted in my best interests. Afterward you advocated on my behalf. You deserve the highest praise. CSH et al rightly deserve its opposite.”

I’m happy to report that Medic and veterans agent Emerling have patched up their differences.

A Soldiers’ Home Companion

When first published on Medic in the Green Time the name of the Salem, Mass veterans agent was fictionalized. On 11 November 2021 the article appeared in CounterPunch, where Medic named the veteran’s agent. Subsequently, the Secretary of Veterans Services for Massachusetts and the veterans agent expressed their strong disapproval of the story. See addendum.

Vicomte de Valvert: Monsieur, your nose… your nose is rather large.

Cyrano de Bergerac: Rather?

Vicomte de Valvert: Oh, well…

Cyrano de Bergerac: Is that all?

Vicomte de Valvert: Well of course…

Cyrano de Bergerac: Oh, no, young sir. You are too simple. Why, you might have said a great many things. Why waste your opportunity?

Edmond Rostand

Cyrano de Bergerac, Scene 1, Act 1

Not long ago my neighbor Carol suggested I apply to live at a soldier’s home. She knew I’d done a tour in Vietnam as an infantry medic in 1970.

I’m on two housing lists but figured why not? I filled out an application; two months later I had an interview at the Chelsea Soldiers’ Home in Boston. On a chilly New England morning veteran’s agent Kim Emerling and I visited the Home. We arrived early and waited in the car. I would have to take a rapid Covid test to enter the three-story building. After a time, a nurse I’ll call Hank emerged from the blue canopied front door.

A tall, muscular man, he carried a basket filled with medical supplies suited to his present task. Ambling toward us, he stopped abruptly to chat with an elderly female veteran. A few minutes later, he leisurely conversed with the driver of a delivery van. During this time Kim growled words which I will not relate. Finally, as if in a dream—mine or his I could not tell—Hank sauntered toward us. I had the curious impression that here was a man bereft of intellect and medicinal insight.

Leaning into the passenger side window, Hank confided that to properly administer the rapid antigen test I would first have to blow my nose. My neighbor had warned me of this. I told Hank “No,” I could not do that.

administer the rapid antigen test I would first have to blow my nose. My neighbor had warned me of this. I told Hank “No,” I could not do that.

“Is that a medical condition?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “My nose will bleed if I blow it.”

Nose bleeds were the scourge of my childhood and continue, though less frequently, to this day. I’ve had my nose cauterized several times. Hank returned to the building to check with administrative staff. He came back a few minutes later.

“You can’t enter without taking the test.”

I had a bad feeling. Something told me things would not go right. What to do? I did not blow my nose, but reluctantly allowed Hank to swab my nasal passages.

“I’ll try to get a good sample,” he said, and swabbed diligently three times inside each nostril.

As Hank inserted the swab into a container, loud and clear I said, “I’m bleeding.” Hank looked up from his task. He saw the blood on my face.

“You weren’t kidding,” he said.

Undeterred—or, inspired by the sight of re liquid dripping down an old man’s chin—Hank said he would return the swab sample to the building, wait fifteen minutes for the results, then revisit me to administer a PCR swab test, also required—with results in five to seven days.

When Hank returned I announced, “Never mind. I’ve lost enough blood for today!”

Almost cheerfully, Hank said he would talk with admin to see if I could enter the building without the second test. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.

Instead, I imagined calling in heavy artillery from LZ Ranch—a remote firebase in Cambodia which I’d had the pleasure to occupy while it was overrun—and moments later I swore I heard the welcoming sound of incoming 155 shells whistling overhead. In the eye of my mind I witnessed their fiery crrrumpBANGs exploding upon the building’s immense front door. Seconds later I fancied power diving Cobra gun ships unleashing salvos of white-tailed rockets, 40 mike-mike grenades, and withering miniguns into the black tarred roof. I imagined that inside the home all was havoc. I was elated. Please note that I am not discounting the proven efficacy of the B40 RPG, the primitive but deadly Chicom grenade, or the wicked tripod-mounted 30. caliber machine gun. In my reverie only American weapons was employed.

whistling overhead. In the eye of my mind I witnessed their fiery crrrumpBANGs exploding upon the building’s immense front door. Seconds later I fancied power diving Cobra gun ships unleashing salvos of white-tailed rockets, 40 mike-mike grenades, and withering miniguns into the black tarred roof. I imagined that inside the home all was havoc. I was elated. Please note that I am not discounting the proven efficacy of the B40 RPG, the primitive but deadly Chicom grenade, or the wicked tripod-mounted 30. caliber machine gun. In my reverie only American weapons was employed.

When Hank returned he asked that I call admin. I did so. A woman I’ll call Linda stated I could not enter the building without taking the slow result PCR test. Three times, quite clearly, I half-shouted, “Miss, I’m bleeding as we speak!” Three times Admin Linda ignored my distress. Anger. I had murderous anger and wilting anxiety, but somehow asked Linda if the interview could be done by phone.

“Absolutely not,” she declared.

I inquired about rescheduling the war. Pardon me. The visit. Linda asked me to wait in the car while she consulted a doctor.

“You can’t enter the building without the PCR test,” she sternly repeated. “But don’t worry. The swab will not enter your brain.”

At this point, bleeding and agitated, somehow, in a civil tone I terminated the visit. Kim, at the wheel all this time, handed me a fresh set of tissues, then us drove back to home sweet Salem.

Kim, a Special Forces command sergeant major who’d seen his share of combat, takes all things in stride. “It’ll work out,” he said. “You still bleeding?”

Two weeks later, for reason’s known only to itself, the Chelsea Soldiers’ Home called and asked if I wanted to reschedule my visit.

“Of course, you’ll have to take the Covid test,” said the polite female caller. “Ahhhhh…No,” I said.

I noted that complaints had been filed with the state Massachusetts Secretary of Veterans Affairs. With the VA Inspector General.

There came a gulping noise. “Oh,” she said.

“Oh,” I echoed, and politely hung up.

A month later I received a letter from the VA IG. My complaint had been forwarded to the Massachusetts Secretary of Veterans Affairs.

A full two months after the initial nasal attack I received a phone call from the director of the Chelsea Soldiers’ Home, the amiable Eric Johnson. Our conversation was cordial. I emphasized the beguiling way my conspicuous bleeding was ignored—by Hank, the Nurse and Admin Linda. The director offered to consider my suggestions on how to improve patient care in anomalous circumstances. Several times he encouraged me to reapply to the Soldiers’ Home.

Politely, I told him, “That’s not gonna happen. But thank you for calling.”

_____________

Addendum

After publication of this story on CounterPunch Medic received an email from retired Special Forces Command Sergeant Major and Salem veteran’s agent Kim Emerling. The story, he noted, had been forwarded to him by Cheryl Poppe, Secretary, Massachusetts Department of Veterans’ Services. He found the article embarrassing. The events related did not represent all the good work he had done with veterans. Medic replied:

“Compared to my website, CounterPunch has a large readership and 11 November gave me the opportunity to tell a true postwar story that would resonate with vets as well as non vet readers. Since the official VA response to what happened to me was late and minimal, putting the story on CounterPunch gave me the chance to vent my anger, though offset with humor.

“I figured it was best not to name the nurse, the admin woman, or Cheryl Poppe and Eric Johnson [the Chelsea Soldier Home Superintendent], but what I wrote about you was favorable, so I felt there was no harm changing Barry Carlson to Kim.

“I regret not telling you that I would use your name, though what I wrote was favorable to you. I’m sorry if the fallout from my CounterPunch article has affected you, but in fact you did nothing wrong. Throughout the ordeal, an inexcusable sequence of events which led to me sitting in your car bleeding, and ignored by CSH staff, you kept me calm. You stayed in control. How is that embarrassing to you?

“Afterward, on my behalf, you contacted Cheryl, who for weeks did not respond. Cheryl Poppe, Eric Johnson, Peter the nurse, the admin woman I spoke to on the phone, all deserve embarrassment–if not more–for what happened to me. None of which reflects on you, an eye witness to those events, or your good work with veterans.

“In summary, I see it this way: advised of an unnecessary injury inflicted on me by CSH medical staff, admin at Chelsea Soldiers’ Home failed to assist a bleeding, 100% disabled, highly decorated combat veteran, who later required specialist medical attention to address those injuries. During that time, as I continued to bleed and experience severe war related anxiety, you acted in my best interests. Afterward you advocated on my behalf. You deserve the highest praise. CSH et al rightly deserve its opposite.”

I’m happy to report that Medic and veterans agent Emerling have patched up their differences.