First published on CounterPunch on 24 July 2019

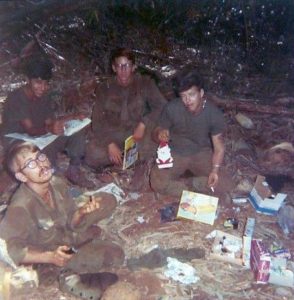

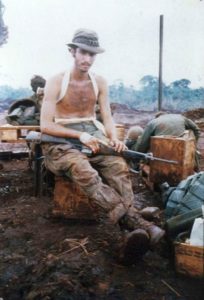

Once, on a good day in a bad war, as we lay in wait, four young men, unsuspecting of what lay ahead, walked into the perfect ambush, and we took no casualties. After we scavenged the bodies for souvenirs, silently, we marched away. An hour later, a colonel had eight gallons of ice cream flown out to us by chopper, and like children, we sheltered beneath the jungle canopy and devoured the rare treat, knowing the enemy could not harm us.

Once, on a good day in a bad war, as we lay in wait, four young men, unsuspecting of what lay ahead, walked into the perfect ambush, and we took no casualties. After we scavenged the bodies for souvenirs, silently, we marched away. An hour later, a colonel had eight gallons of ice cream flown out to us by chopper, and like children, we sheltered beneath the jungle canopy and devoured the rare treat, knowing the enemy could not harm us.

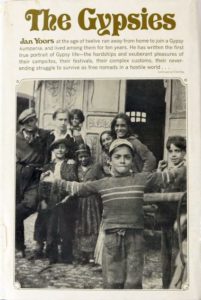

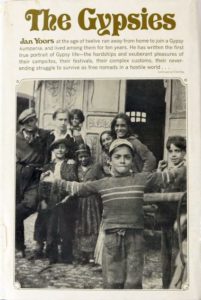

Most often, once a week ammo, C-rations and water were flown to us. Log days, we called them. From among the paperbacks the Army tossed into the red mail sack, I grabbed The Gypsies by Jan Yoors. The cover photograph depicted a group of boys–children really, with one youth–showing off, his arms outstretched, his face a hardening smile. In the background, a somber young man, hair rakishly swept back, stares directly into the camera. At age twelve, Yoors had run away from home, joined a group of Gypsies, for ten years lived and traveled with them, immersed himself in their pleasures and ordeals, their secret sorrows. His once popular book details the true Gypsy way of life, and their struggles to live in a world hostile to their nomadic freedom.

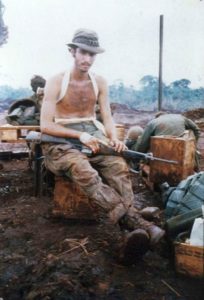

For several weeks in Vietnam’s scorching heat I carried that book, found sanctuary  in it, brought home this paper souvenir, the last page, smudged with Vietnam’s unique red dirt, used as a diary to record our losses.

in it, brought home this paper souvenir, the last page, smudged with Vietnam’s unique red dirt, used as a diary to record our losses.

Fast forward to winter 2019. My friend Paul Saint-Amand, who lives in Rockport, MA, mentioned Jan Yoors while making small talk. I replied how I knew his book, how much it meant to me. By remarkable coincidence Vanya, Jan’s son, was Paul’s next door neighbor. He offered to introduce us.

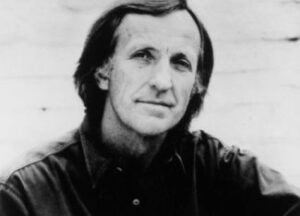

On July 4th, at a Veterans for Peace gathering in Rockport, while a cluster of old timers sat, ate and gabbed before heading out to march in the town’s annual parade, I sat in the cozy living room of Vanya Yoors, with his wife Christine, their two dogs, and Marianne Yoors, Jan’s ninety-three-year-old-widow, just then visiting from New York. Jan, known for his writing, photography, and tapestry weavings, had two wives simultaneously, but that is a story for another time.

For a quickly passing hour, as if the terrible events were just then unfolding, Marianne, seated on a comfortable couch, recollected her war experiences in Nazi-occupied Belgium. The Germans had rounded up many of her friends, she said. Hauled them away. When her father was arrested she banged on the door of the Nazi commandant, defiantly strode into his office, and demanded to know her father’s whereabouts. There was nothing to be done, said the high ranking officer. The train had departed to Auschwitz.

“I could have done more,” said Marianne. For him, for all the others.

“I could have done more,” said Marianne. For him, for all the others.

Vanya, who may have heard this story of survivor’s guilt more than once, knowingly disagreed.

“You, a young Dutch girl with a Jewish father–a teenager, did all you could,” he replied. “All you could do.”

Jan had fought for the French resistance, said Marianne, was captured, incarcerated for months, then released, but the torture had taken its toll. Cruel scars covered his body. He was never the same. And never talked about it.

There is no inkling of torment in Jan’s vibrant book on gypsies. War is the subject of his Crossing: A Journal of Survival and Resistance in World War II. Marianne said her husband’s biography, written by a best selling academic, lacked the gut felt sensibilities of war, its grit, suffering, and sorrow. During all this time I listened attentively, making only an occasional remark.

“You were in war?” asked Marianne.

I nodded yes. “Vietnam.”

“It’s in your eyes,” she said. “I see this in your eyes.”

As Marianne related other events she had witnessed, her war time seeming to invade the very room in which we sat, I was impressed by her remarkable inner strength, though within her she held much grief. Then it was my turn to tell a story. I told how one evening, twenty-five years ago, friends played a few minutes of a recording of Gorecki’s Symphony No. 3, a work commissioned in response to the Holocaust. I was moved by it, and a few months later, while house sitting, I put on the same recording, turned off the lights, and lay back in a large comfortable chair. By the second movement I began to weep, then sob, and soon felt a great unburdening, as if something deep inside me, long held back, set itself free. When the beautiful sorrow ended, for hours on end I replayed the music, and continued to weep. In college I had written about war stress, but did not think I had it.

Perhaps Marianne might listen to this music? Perhaps, she said.

When it came time to leave Marianne wrestled herself up from the comfy sofa, stepped toward me, and proceeded to clasp me in the arc of her arms. “Give me a hug,” she demanded. And I did. “No. Give me a real hug,” she said, and once, twice, three times, vigorously she pulled me to her.

I said goodbye to Vanya, to his wife, then off I went, to rejoin my friends, who were readying for the parade.

Under a blazing summer sun, the Fourth of July march, an annual Rockport tradition, covered one hilly mile and took two hours. Proceeding at an uneven pace, at times slow and steady, at times zipping along, six Veterans for Peace old timers, proudly bearing VFP’s black and white flags, a colorful banner, and jaunty anti-war signs, as always, brought up the rear. Ahead of us, a variety of civic and community groups, local sport teams, assorted clamoring bands and musicians, two wailing fire trucks, the occasional New England-themed float.

For the entire length of the parade, along either side of the two-lane road were stately white-painted century old New England houses–in front of them, crowds three and four deep, the lively people mostly white, and many perhaps of considerable privilege and wealth.

For the entire length of the parade, along either side of the two-lane road were stately white-painted century old New England houses–in front of them, crowds three and four deep, the lively people mostly white, and many perhaps of considerable privilege and wealth.

At every bend in the road, along each brief straightaway, the townspeople cheered us as we marched by. Long, almost joyful applause filled the humid air. Looking about, I detected an occasional look of chagrin, or reluctant knowing nod.

During and after the initial years of Afghanistan and Iraq these same good people had booed and hissed as we strode by, taunted us with crude remarks, turned their angry backs upon us. For a quarter mile I pondered who or what had changed their minds; the question, I soon realized, was irrelevant. The citizens of Rockport had grasped the truth, and that’s what mattered.

At a curve in the road, standing still, waiting for the bottleneck to clear, from my  right came a sudden movement: a familiar figure ambled from the crowd, beckoned me toward her. Another immense hug. Vanya snapping the picture. Clearly our war experience was a bond between us.

right came a sudden movement: a familiar figure ambled from the crowd, beckoned me toward her. Another immense hug. Vanya snapping the picture. Clearly our war experience was a bond between us.

A quarter-mile later, as the sun began to set, the spirited march, once past the judges reviewing stand, came to a welcoming end. Back home in Salem, rested up, I contemplated how that afternoon, in a comfortable and pleasant seaside town, Marianne Yoors, aged widow of a WWII veteran–had told me her tales of a dreadful time, stories that demand our attention, so that presently, we do not relive her past, but act to assure our future.

addendum

Medic subscribes to The Three Penny Review, a literary journal in newspaper format published four times a year. The spring 2020 issue contains a short article by Irene Oppenheimer in which she recalls her family’s tiny three room apartment in New York’s Little Italy, the parks near Greenwich Village, and how, as a student, an older woman asked her to model for her artist husband. Irene details the modeling experience, and how Jan Yoors got a little too close for comfort. Last week I emailed Irene, and mentioned the article above. From Los Angeles she wrote back. In passing, Irene said her former husband was a member of Veterans for Peace, and she named him. To my surprise, I had met Jay Wenk twenty years ago when visiting VFP friend Dayl Wise (Echo 2/5 First Cavalry ’69) and his wife, the poet Allison Koffler, in Woodstock, NY. Irene has graciously accepted the offer to hear from Vanya.

____________

Regis Tremblay’s excellent video of the parade.

Wikipedia: Jan Yoors

Jan Yoors’s website

The Gypsies, Kirkus Review

New York Times, Marianne Yoors

Gorecki interprets Symphony No.3

A Discomforting Letter From A Comfortable Town

First published on CounterPunch on 24 July 2019

Most often, once a week ammo, C-rations and water were flown to us. Log days, we called them. From among the paperbacks the Army tossed into the red mail sack, I grabbed The Gypsies by Jan Yoors. The cover photograph depicted a group of boys–children really, with one youth–showing off, his arms outstretched, his face a hardening smile. In the background, a somber young man, hair rakishly swept back, stares directly into the camera. At age twelve, Yoors had run away from home, joined a group of Gypsies, for ten years lived and traveled with them, immersed himself in their pleasures and ordeals, their secret sorrows. His once popular book details the true Gypsy way of life, and their struggles to live in a world hostile to their nomadic freedom.

For several weeks in Vietnam’s scorching heat I carried that book, found sanctuary in it, brought home this paper souvenir, the last page, smudged with Vietnam’s unique red dirt, used as a diary to record our losses.

in it, brought home this paper souvenir, the last page, smudged with Vietnam’s unique red dirt, used as a diary to record our losses.

Fast forward to winter 2019. My friend Paul Saint-Amand, who lives in Rockport, MA, mentioned Jan Yoors while making small talk. I replied how I knew his book, how much it meant to me. By remarkable coincidence Vanya, Jan’s son, was Paul’s next door neighbor. He offered to introduce us.

On July 4th, at a Veterans for Peace gathering in Rockport, while a cluster of old timers sat, ate and gabbed before heading out to march in the town’s annual parade, I sat in the cozy living room of Vanya Yoors, with his wife Christine, their two dogs, and Marianne Yoors, Jan’s ninety-three-year-old-widow, just then visiting from New York. Jan, known for his writing, photography, and tapestry weavings, had two wives simultaneously, but that is a story for another time.

For a quickly passing hour, as if the terrible events were just then unfolding, Marianne, seated on a comfortable couch, recollected her war experiences in Nazi-occupied Belgium. The Germans had rounded up many of her friends, she said. Hauled them away. When her father was arrested she banged on the door of the Nazi commandant, defiantly strode into his office, and demanded to know her father’s whereabouts. There was nothing to be done, said the high ranking officer. The train had departed to Auschwitz.

Vanya, who may have heard this story of survivor’s guilt more than once, knowingly disagreed.

“You, a young Dutch girl with a Jewish father–a teenager, did all you could,” he replied. “All you could do.”

Jan had fought for the French resistance, said Marianne, was captured, incarcerated for months, then released, but the torture had taken its toll. Cruel scars covered his body. He was never the same. And never talked about it.

There is no inkling of torment in Jan’s vibrant book on gypsies. War is the subject of his Crossing: A Journal of Survival and Resistance in World War II. Marianne said her husband’s biography, written by a best selling academic, lacked the gut felt sensibilities of war, its grit, suffering, and sorrow. During all this time I listened attentively, making only an occasional remark.

“You were in war?” asked Marianne.

I nodded yes. “Vietnam.”

“It’s in your eyes,” she said. “I see this in your eyes.”

As Marianne related other events she had witnessed, her war time seeming to invade the very room in which we sat, I was impressed by her remarkable inner strength, though within her she held much grief. Then it was my turn to tell a story. I told how one evening, twenty-five years ago, friends played a few minutes of a recording of Gorecki’s Symphony No. 3, a work commissioned in response to the Holocaust. I was moved by it, and a few months later, while house sitting, I put on the same recording, turned off the lights, and lay back in a large comfortable chair. By the second movement I began to weep, then sob, and soon felt a great unburdening, as if something deep inside me, long held back, set itself free. When the beautiful sorrow ended, for hours on end I replayed the music, and continued to weep. In college I had written about war stress, but did not think I had it.

Perhaps Marianne might listen to this music? Perhaps, she said.

When it came time to leave Marianne wrestled herself up from the comfy sofa, stepped toward me, and proceeded to clasp me in the arc of her arms. “Give me a hug,” she demanded. And I did. “No. Give me a real hug,” she said, and once, twice, three times, vigorously she pulled me to her.

I said goodbye to Vanya, to his wife, then off I went, to rejoin my friends, who were readying for the parade.

Under a blazing summer sun, the Fourth of July march, an annual Rockport tradition, covered one hilly mile and took two hours. Proceeding at an uneven pace, at times slow and steady, at times zipping along, six Veterans for Peace old timers, proudly bearing VFP’s black and white flags, a colorful banner, and jaunty anti-war signs, as always, brought up the rear. Ahead of us, a variety of civic and community groups, local sport teams, assorted clamoring bands and musicians, two wailing fire trucks, the occasional New England-themed float.

At every bend in the road, along each brief straightaway, the townspeople cheered us as we marched by. Long, almost joyful applause filled the humid air. Looking about, I detected an occasional look of chagrin, or reluctant knowing nod.

During and after the initial years of Afghanistan and Iraq these same good people had booed and hissed as we strode by, taunted us with crude remarks, turned their angry backs upon us. For a quarter mile I pondered who or what had changed their minds; the question, I soon realized, was irrelevant. The citizens of Rockport had grasped the truth, and that’s what mattered.

At a curve in the road, standing still, waiting for the bottleneck to clear, from my right came a sudden movement: a familiar figure ambled from the crowd, beckoned me toward her. Another immense hug. Vanya snapping the picture. Clearly our war experience was a bond between us.

right came a sudden movement: a familiar figure ambled from the crowd, beckoned me toward her. Another immense hug. Vanya snapping the picture. Clearly our war experience was a bond between us.

A quarter-mile later, as the sun began to set, the spirited march, once past the judges reviewing stand, came to a welcoming end. Back home in Salem, rested up, I contemplated how that afternoon, in a comfortable and pleasant seaside town, Marianne Yoors, aged widow of a WWII veteran–had told me her tales of a dreadful time, stories that demand our attention, so that presently, we do not relive her past, but act to assure our future.

addendum

Medic subscribes to The Three Penny Review, a literary journal in newspaper format published four times a year. The spring 2020 issue contains a short article by Irene Oppenheimer in which she recalls her family’s tiny three room apartment in New York’s Little Italy, the parks near Greenwich Village, and how, as a student, an older woman asked her to model for her artist husband. Irene details the modeling experience, and how Jan Yoors got a little too close for comfort. Last week I emailed Irene, and mentioned the article above. From Los Angeles she wrote back. In passing, Irene said her former husband was a member of Veterans for Peace, and she named him. To my surprise, I had met Jay Wenk twenty years ago when visiting VFP friend Dayl Wise (Echo 2/5 First Cavalry ’69) and his wife, the poet Allison Koffler, in Woodstock, NY. Irene has graciously accepted the offer to hear from Vanya.

____________

Regis Tremblay’s excellent video of the parade.

Wikipedia: Jan Yoors

Jan Yoors’s website

The Gypsies, Kirkus Review

New York Times, Marianne Yoors

Gorecki interprets Symphony No.3