In 2008 Medic met the distinguished photographer Jeff Wolin, then working on his book Inconvenient Stories: Vietnam Veterans. Jeff has kindly lent permission to excerpt several of those stories and their accompanying photographs.

Benito Garcia

Benito Garcia

173rd Air Borne, PFC

May 1965-1966;

1966-1967; 1968

“The first time I saw a dead American, there were three of them-their heads were up on stakes. It was in ‘D’ zone, not too far from Bien Hoa. The enemy was doing that to scare us. Of course, it didn’t scare us; it made us angry. It made me angry. By this time I was lost in the jungle. I was alone. I was AWOL-I weighed 112 pounds; they wanted me to hump a spare barrel of an M60 machine gun. I had just gotten out of the hospital two weeks before with appendicitis. I’m thinking, ‘I’m not in shape. I can’t do this job. I’m leaving!’

I ran off and then I stopped. ‘What in the hell are you doing? You’ve never been in the jungle before!’ By this time it was too late. I was lost, separated from my unit. That’s when I ran across the heads. I found the individuals that did it. I heard them down the hill by the river and there was one over where the heads were and he was masturbating. I was going to try to take him prisoner but I stumbled and I stabbed him accidentally with the bayonet. Once I did that I had to kill him. And when the other two came up I shot them both and I cut off their heads. Some of the guys from the 101st Airborne used to call me ‘headhunter.’

At first I did it because I was enraged but then it was a way to score points-that’s how you were esteemed by your peers. It didn’t bother me back then. But now I don’t sleep more than 15-20 minutes at a time and then I wake up with nightmares and chills and sweats. I walk the perimeter at night. But that’s my cross to bear. I see children when you’ve killed their parents-you hear them crying.

I proudly endured that I stood my post; I did what was expected of me. My fellow paratroopers respected me despite the fact that I was a fuck-up in the rear. In the boonies I did my job. Today I have to suffer with that. No big deal. Thank you very much for your tax dollars-the VA pays for it. Georgie-boy, when he came in as president, they started cutting our benefits. I’m at 150% disability: 100% for PTSD; 30% for diabetes; 10% for erectile dysfunction and 10% for organic brain damage. I’m in pain all the time but you get used to it. They give me medication but it doesn’t work. What does help is marijuana but the sons of bitches won’t let me have it. I don’t want no more drugs. They want to give me codeine, heavy narcotics, but that counteracts the Viagra and I’d rather have a hard-on and endure the pain than just be a fucking zombie…

Here we are in the middle of the night-it’s drizzling-me, Doc Wheatfield, a guy we called Cherry, John Wekerly, and some others. We go and there’s a girl lying under a huge banyan tree. The only other one there is a little boy. She’s pregnant, about to deliver a baby. We break out our ponchos and Doc Wheatfield gets underneath and delivers the baby. We felt responsible for the baby. Doc asks one of the guys to get some fruit from the C-rations. I said, ‘Doc, no one’s going to give up their fruit.’ Doc was a Christian man. He said, ‘Oh, ye of little faith.’

The guys came back with a big sack full of canned fruits. We gave her whatever we had in money and fruit. And then a mama-san arrived and first she looked at us real mean like ‘you murdering bastards.’ But then she saw the food, money, the baby was fine, the little shelter we had built and she came and stood in front of us and she bowed.

It was raining, like I said, but when the baby came out there was a clap of thunder and it stopped raining and the baby cried out. You could hear it in the whole valley. We were so proud and so happy and some of us were crying. As soon as we started to leave, here comes the rain again. We were walking along a rice paddy, standing out like a sore thumb if there was a sniper on the hill, especially when the lightning flashed. There was a herd of water buffalo and someone says, ‘Look at that deformed cow!’ It was a cow having a calf. People from ranches will tell you this: a bull knows its babies and will allow the mother to have a calf but other bulls don’t give a damn. So here we are in the middle of the rain holding hands in a circle around this cow while Doc Wheatfield is helping deliver that calf.

We went over there as regular kids doing a tough job. Some of us lost our way. We did bad things when we were required to but at the same time when it came to helping the innocent, we helped. We were noble. Our hearts were good and those good hearts got wounded.

After the war we were treated disrespectfully. We were persecuted. In the ’70’s over 30% of federal prison inmates were Vietnam veterans. I was one of them. On Mother’s Day, my father, Benito Garcia, a police officer, arrested me for robbing banks. In 18 days I robbed 6 banks in Chicago. I’d go in with a .25 automatic pistol with .22 ammunition-I didn’t even have a gun that shot. I was not very good at it. Then I hung up my guns and picked up the books while in prison. In 16 months I received my Associates degree in Secondary Education from Vincennes University. I earned enough credits for a Bachelors degree from Indiana University in Sociology.

In prison I felt comfortable because I know how to be in a society of macho men. I was always alert, always tense. I could deal with that environment-it was the jungle with steel bars. I could function there; I couldn’t function out here-it’s still difficult. I served 6 years, 1 week active military service and 6 years, 3 months in prison. I got my degree; I was released and I was everybody’s success story. Harry Porterfield did a 30 minute segment on me for the CBS Chicago affiliate.

I was successful for a while but then the nightmares about ‘Nam started and I had to drink. The only way I can get through the night without getting up is when I’m passed-out drunk. But I haven’t had a drink since ’95 when I got in trouble again. An east Texas judge wouldn’t believe that I was a thrifty shopper and that the 320 pounds of marijuana in the trunk were all for me. I wound up in a Texas prison. I served 3 years, 3 months. I am presently on parole for that offense-possession of marijuana, not distribution. When I got out I had 89 months of parole-I’ve got 14 months left. I successfully completed the parole for my bank robberies and I expect to successfully finish this one. I won’t smoke now, but come December 27, 2005, I am going to roll a fucking joint the size of a bus and I’ll kill it in one drag.”

R. Michael Rosensweig

U. S. Army Rangers Specialist E-4

1969-1971

“After my first tour of duty in Vietnam I had orders for Fort Bragg. I got back to the states and at that time my family was in Baltimore. I was walking up Howard Street in downtown Baltimore—I was still in uniform. A truck backfired about two blocks behind me. I just yelled, ‘Incoming!’ and hit the pavement. It just freaked everybody out. I said, ‘To hell with this.’ Next morning I took the bus, went down to the Pentagon and had orders changed to go back to ‘Nam—just wasn’t ready to come back to what we like to call ‘civilization.’ I wasn’t done fighting my war—there was still a cause to be fought for.

I enjoyed the combat—the adrenalin. Don’t mistake that. Don’t mistake the love of combat for the lack of fear. We were all scared—just some of us got off on the adrenaline…

As far as getting orders changed, it was no problem. I just went down there, told them I wanted a change to go back to ‘Nam. Eighteen days later I was back in country. I went through Rangers school—we had our own school in Vietnam. It was ten days of sheer hell. Our training was geared to guerilla fighting. I was stationed in the same area as my first tour, Central Highlands. The company was based in An Khe.

I loved being with the Rangers. We were a six-man hunter-killer team. Our mission was to go out and kill. Go in, strike, get out—covert. Sometimes if there were too many NVA we had to call in air strikes. Sometimes we had to call them in a lot closer than was allowed by military regs. In some cases it was do that or die anyway.

War just leaves scars that will never heal up in your head because of the overall trauma. The first person I ever had to kill was an eight-year old boy. We were escorting the 101st Airborne in the A Shau Valley. A little boy ran out of the village with a grenade in his hand heading straight for a truckload of GI’s—kind of hard to balance that one out. The grenade was in his hand. We tried to get him to stop—‘Dong Lai!’ ‘Stop!’ He just kept running with that Chi Com in his hand—it’s a Chinese Communist grenade with a string fuse. We didn’t have a choice. If we hadn’t killed him he would have ended up throwing it in a truckload of GI’s. He was about 25 yards away. There are too many other instances like this to list and I say that in all sincerity. I just can’t talk about them.

They deactivated my company just a few months after I left when they started the withdrawal. A lot of guys who stayed went to either Special Forces or went to work for the CIA as black ops in Cambodia. The time I served with the Rangers was the pinnacle of everything I’d ever wanted to be. And when I lost that, I couldn’t see past the war.

They sent me to Germany to an artillery unit as a mechanic and four months later I was out. A couple of Puerto Rican guys from New York were having some kind of big war among themselves and they made the mistake of coming through my room in the middle of the night. You don’t just take somebody fresh out of combat and startle him in the middle of the night because he ain’t going to hide his head under the covers—he’s coming out attacking. And that’s what I did. The first I threw out the window; the other I pinned up against a locker and stuck a bayonet right up against his throat. I almost killed two of our guys—four months later I was out. There’s a lot of stuff especially with the Rangers that’s still classified and I can’t talk about.

I have plenty of firepower. I stay pretty heavily armed at home and everybody that knows me knows better than just to drop in—I’m in my bunker. The woman I was married to for fourteen years was scared to death of me the whole time we were married because of the nightmares—wake up in the middle of the night crying, screaming, roaming around.

You know, because of my background in Vietnam, we had to watch our tempers more than anyone else. Society did not give us the right to get angry and shout. If we did that we were considered lethal. I got fired more than once just for doing nothing more than anybody else would have done—got mad at somebody for doing something really stupid. Yelled at him. The reason I was given was because when I get mad, all people see in my eyes is death.”

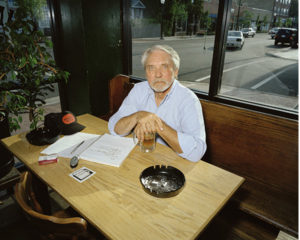

Larry Heinmann

Larry Heinmann

25th Infantry Division

APC Driver 1967-1968

“On New Year’s Eve we started getting radio messages from LP’s in the woods-three-man listening posts, ‘Something’s happening! Something’s happening! Something’s happening!’ The fighting started about 11 o’clock at night and went steady, on and off, until the next morning, until it got light enough to see-then it stopped.

I will never forget this. I know I didn’t dream it. I haven’t imagined it. The sun came up and the smoke cleared and the dew burned off. There was meat all over everything. All around the perimeter it was meat. And the wood line, which was maybe fifteen or twenty meters away looked like ruined drapes. It was a mess.

One thing that Oliver Stone, who described this battle in Platoon, got right-at the end of the firefight in the film the planes come in and drop napalm, which didn’t happen; they didn’t drop anything on us. The next morning when the kid wakes up there’s white powder all over everything. Everything sort of looked antique-I remember that distinctly. It was dust and junk all over everything. Everybody was covered with dust and sweat. And the bodies and the body parts, the meat, looked antique. Not fun. I never want to go through something like that ever again.

One of the things I did at the beginning of the battle: my track had been on the perimeter and then they moved us to a new spot on the perimeter. I parked the track in such a way that the gas tank was as far away from a direct shot as possible. There were some tracks that got blown up and burned to the ground. The gasoline fire melted the metal armor-around a couple of the tracks you’d have this huge puddle of aluminum alloy. One of the tracks in our platoon got hit and burned and the driver’s body was simply incinerated. All we found of him was a bit of his backbone, his pelvis and his skull.

As drivers we were sitting in the track from the neck down so you can see; everyone else is sitting on top. If an RPG hit the track, the driver has the gas tank right behind and the drivers always got fucked. If I ever meet the bonehead who sent gasoline powered Armored Personnel Carriers to Vietnam instead of diesel, which is less flammable, he and I are going to have a real serious conversation. I would gladly do time in prison for the privilege of beating the shit out of the guy…

It’s a true fact if ever there was: I became a writer because of the war and not the other way around. It’s one of the great ironies of my life and it’s an irony I share with a number of writers who came out of Vietnam. Bruce Weigl would be working in a mill around Lorain, Ohio. Probably the only writer I know who would have been a writer regardless of the war is Robert Olen Butler.

My old man drove a bus and had four sons. Word in the house was: finish high school and get a job. I’m the only one of the brothers who finished college. Becoming a writer was the farthest thing from my mind. I came back from Vietnam in early spring of 1968. Three weeks later Martin Luther King was murdered. Then in June, Bobby Kennedy was murdered. I got a job that summer driving a Chicago city bus and literally drove through the big doings at the Democratic National Convention in August. I thought the war had followed me home.

I wanted to go back to school. I took a writing class because I thought it was going to be a snap ‘A’ and I wouldn’t have to work. I got fooled. The second night of class the teacher comes up to me and says, ‘If you want to write war stories, here, read these two books.’ And he hands me The Iliad and War and Peace; it took a year to read those books. The Iliad is a paradigm for a lot of things but it’s a war story so it’s a paradigm for war stories.

I became a writer because I had a story that would not be denied. I was talking about this the other day with my editor and I said, ‘For 35 years I’ve been thinking about the war every day.’ The war had a tremendous impact on my life. When my kids were old enough I had to teach them not to come up behind me and give me a hug around my throat. Don’t make a loud, sudden noise behind me. I’ve always had a kind of tic and I went to the VA and the shrink said it was some kind of seizure. It’s a flashback. It only lasts an instant but you get a full image of an event.

As a writer Vietnam is my subject. Faulkner had Yoknapatawpha County and he had that in his head all his life. All he had to do was dip in this story or that story and the characters were all right there. Garrison Keillor had Lake Wobegone-what a remarkable discovery! I used to be embarrassed to write about the war-not so much now. I’ve been blessed with a source. I know for a fact that as a writer I can reach around and touch the war and always find a story. The war really did give me something that I love-writing is a craft that I love.”

Medic’s friend, and a friend to many who knew or studied with him, Larry Heinemann died on 12 December 2019. He will be deeply missed.

Simba Wiley Roberts

Simba Wiley Roberts

U.S. Army Specialist E-5

1968-1969

“Everybody was real tight in my platoon—we were like a brotherhood in the field. There were a lot of dudes we called the ‘blue-eyed souls’. They realized, ‘Hey we’re all over here together. We should be sticking together.’ These were the white guys who didn’t mind walking with the brothers because the brothers got together over there. The only racial problems were back in the rear with the punks with the gear. We’d come in from the field to the base at Pleiku. They wanted us to give up our guns so we stayed in the motor pool with our tanks—told them we were part of the ‘quick reaction force.’

I remember this one particular time, me and a bunch of the guys walked into a bar on the base. There were these guys sitting there in new fatigues and shined boots and looked like they ain’t never been out in the sun. And it was generally like that. The majority of the guys in the rear with the gear were white. And one of them said, ‘Here come a bunch of them damn boonie rats.’ Another said, ‘Yeah, boonie rats, niggers. It’s the same.’ You know, stuff like that. We just walked by.

It was an enlisted mens club. I would roll up my sleeves so my E-5 rank would not show and I could go in with my buddies, because the majority of my buddies were E-4 and below. And I didn’t like going into those clubs where they only played country western. Plus this club had the best entertainment: Philippine girls singing like Diana Ross: ‘Stop in the name of love.’ Everybody was going, ‘Yeah! Sounds like Diana.’

But we was in there and I’ll never forget that night because those guys were throwing beer cans at us. About ten beer cans came flying over from them chumps and we still said, ‘Hey, man, let it go.’ Everybody got a frag grenade in their pocket. It kept going and eventually the place started to close so everybody was talking and I said, ‘Hey, man, let’s just go out and deal with this right now.’ I’m thinking my buddies heard me. So I walk out of the club all bad and this little short guy, kind of bald-headed, said, ‘Yeah, that’s right, nigger!’

And man, I punched him upside his face and was working him over. I picked him up; I had him down. I felt kicks in the back of my head—apparently my boys didn’t hear the word; it was just me out there on the ground. All of a sudden it felt like an earthquake, like a stampede and then the fight really broke out—those crazy dudes from the tanks were ready. They were tearing up folk, man. And I remember grabbing that little guy by his leg and dragging him out of the mess so I could work him over some more. That was funny, man. I hope that guy’s doing ok today.

The MP’s came and we all started running. We didn’t know our way around base camp. I remember falling in these drainage ditches because there was so much rain up there in the Central Highlands in the monsoons. And man, I remember falling into ditch after ditch. Nobody got caught; we all got back. We laughed about it…

After I got home to East Texas, me and Ray, a Vietnam vet buddy of mine, went to pick up the money the Army owed us. We were so happy. We’d been all over the world. I was based in Germany, man. I didn’t go out on the town for a year. I couldn’t. When people asked me, I said, ‘No, man. Where I come from you don’t do that with white folks.’ For a whole year me and the Playboy bunnies had an intimate relationship. But after going home to Texas on Christmas leave and finding my first love in the arms of another man—after I had been so true to her for a whole year—I was numb. So I finally went downtown in Erlangen, Germany; I was making up for lost time. I met a woman named Heidi, which was a blessing. Then I was in Vietnam for a year. There was a thing among African Americans: my father and every generation going back fought for our country in whatever war was going on.

Anyway, me and Ray drove over to Fort Polk, Louisiana to get our money. There was a little club on the way back where we wanted to stop and have a beer. We walked in this place and the guy said, ‘We don’t serve niggers here.’ I looked at Ray and he looked at me. He said, ‘Did he say what I thought he said?’ I said, ‘Yeah, he did, Ray.’ He said, ‘All right, let’s go.’ Can you imagine? I’d been all over the world and everywhere I was a man except when I came back to America.”

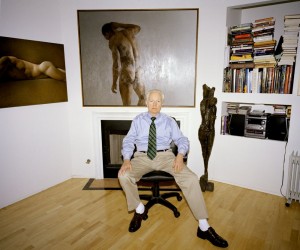

Grady Harp

Grady Harp

U.S. Navy Physician Lieutenant

1968-1969

We docs had a lot of resentment being taken away from training and going to a war we didn’t believe in, but the saving grace for us was that we weren’t going to fight or kill anyone—we were going to treat sick people. And so you tried to erase everything else from your mind except, “I might as well be a doctor over there as a doctor over here.” Time has taught us that physicians who take part in a war are much better surgeons and physicians because you learn to react instantaneously without scratching your head. That kind of training is invaluable. I trained at Los Angeles County Hospital, which is its own Vietnam with the gang wars and all. So I was used to that kind of pace.

You could forget about the war because your concentration was on patients, until those times when the fighting stopped, until you go into periods where you had to deal with the guys falling apart emotionally. When they weren’t having to go out and shoot, they just had to sit back and look at what was happening, make a count of how many friends they had left and wonder what was going to happen next.

Vietnam was a war with no front. The front was underneath you; it was behind you; it was beside you. The method of survival in Vietnam was for the Vietnamese to be dedicated to the U.S. troops during the day because we were fighting North Vietnam, but the Viet Cong were so embedded in the country that even though they had a different allegiance, they were so threatened that the South Vietnamese who worked for us worked for the VC at night. Someone could be very devoted to you as a doctor—your private nurse, or your house mouse, the women who came and cleaned and kept our boots free of snakes—but at night they might get orders that they had to go in and destroy us.

We had an instance where a couple of Vietnamese nurses who worked for us burrowed into one of our bunker hospitals one night and opened fire killing all twenty-six patients that they’d been treating plus three of the corpsmen. One of these was a brilliant surgical nurse. She was captured by the Marines the next day. It was discovered what she had done and so the Marines tied her to two helicopters that took off and pulled her body apart.

It was hideous conceptually, and it was deplorable but when you were fresh from what just happened, it was difficult to admit that you almost had a feeling that that was ‘okay.’ Once you got some distance from it, you knew what pressure she was under so that you got the guilts for ‘participating.’ We’ve all heard the stories about My Lai and Lt. Calley and about Abu Ghraib in Iraq. Unless you’ve actually been in that situation, it’s hard to imagine man’s inhumanity to man. When you’re in the middle of it, sadly, it somehow doesn’t seem so heinous, so inhuman. It’s only upon reflection that you then absorb part of the guilt of what I think this whole nation has for what we did to Vietnam.

One of the things that was most difficult to deal with was the number of guys who had self-inflicted wounds trying to stay out of the field. We had a kid come in—it was back on the hospital ship. He was just one medevac, one grunt, probably only seventeen, underage for the military, a sweet kid. He was going to be sent up the Cua Viet River into a situation where it was guaranteed, being so low on the totem pole, that he was going to be killed. And he was so terrified about it that he decided to shoot himself. What he wanted to do was simply shoot his toe off but he missed and got his ankle instead. They brought him in on a chopper in the middle of the night. He was in such denial. He said, “I’m not going to go up that river. Don’t cut my fucking foot off!”

I said to him, “There’s no foot to come off. It’s already off.” And he said, ‘I won’t stay here any longer. I did it myself.’ I tried to rationalize with him. “Whatever the shot was that did this, your foot is not there.” Finally, one of the corpsmen raised his bootless leg up and showed him his foot was gone. Then the stunned kid turned his story around and said he stepped on a mine—he would be court-martialed if he shot it off himself. I tried to never find out how that was dealt with by the authorities.

It happened frequently. Guys would stab themselves in the hand or refuse to soak their feet in the saltwater baths so their jungle rot would get really bad—anything to stay out of the field. The guys would confide in you because they didn’t look at us as ‘military’—it was a doctor/patient relationship. They knew I wasn’t going to report them; I never reported anything like that. I was very against what was going on and I wasn’t about to turn a kid in who was so desperate that he would do something like that to himself. What human being would?

As a doctor you had to commit to two years of military service. If your first year was in Vietnam, you could choose anyplace in the U.S. for your second year. I’d always wanted to live in New England so I was assigned to the Fargo Building, the Marine Corps Brig in Boston, which is down by Jimmy’s Harborside Restaurant. I couldn’t afford to live close to that. I lived in a little village, Newton Upper Falls above Wellesley—beautiful countryside. I chose it because it would show all four seasons, and maybe that would let me have a year of purging everything.

The first time I drove to work—I had a new VW Squareback and I was in uniform—I took a shortcut to go through Harvard Yard. I’d never been to Harvard and I wanted to see what it looked like. When the students saw my uniform on campus, they pulled me out and beat me up. I somehow got back to the car and drove to my station. I ran into the commanding officer. I didn’t look very good and I told him what happened. He said, ‘Never wear your uniform off base.’ And I said, ‘With all due respect, I’m not going to wear my uniform this year at all.’ So I didn’t.

And you know, now with a little bit of hindsight and a lot of time passing, I can understand that it wasn’t me being attacked, it was the idea of the uniform and people being against the war. They had no idea that I was a doctor. I represented the ugly other that everybody hated. So that’s what they were beating up. They weren’t beating up Grady, a doctor, who had been in Vietnam basically as a civilian. But it gave all of us who’d been through the war a really different outlook on protesters. Even though I protested the war, I fell victim to what protesters can do and that’s emotionally intolerable.”

James Spilman

James Spilman

U. S. Army Specialist E-4

1969-1970

I think it was July 3. We just came in on a three-day stand-down when they came to us about 8:00 at night. “Get ready to go. We’re going to send you out—there’s movement in the area. We think they’re building a base camp and we want you to check it out.”

So we went out that night and set out at the bottom of a hill and started up. Delta Company was on the other side and they walked into a horseshoe-shaped, battalion-size NVA base camp. It cut them to pieces. The NVA opened up with automatic weapons fire. I got behind a log. Every time I’d raise my head to look out, someone with an automatic would open up. I’m lying there thinking, ‘They’re going to walk up and shoot me in the head.’

You could hear guys hollering for the medics. The NVA had gotten in between my unit and had gotten people’s dog tags and called out their names saying they’d surrendered. An NVA called, ‘Medic, medic!’ and when the medic got there he got shot in the face.

Once we took the hill we found no NVA soldiers—not one dead body. There were GI’s all over the place. They put us on a detail picking up the bodies—take a poncho, roll the guy in the poncho, drag him down the hill. I don’t know how many of our guys we dragged down. I couldn’t look at them any more. It really bothered me. I was thinking, ‘I could be dead too.’…

I lost a friend named Ross. A week before he was killed, he and two other guys came across four or five NVA soldiers eating. Instead of shooting them they got into hand-to-hand combat and killed the NVA. They were decorated. I thought he was really brave.

We were in a firebase and it was morning when I saw him approaching the base. I was standing on a bunker and I yelled out, ‘Hey, Ross, come on; I’ll buy you a beer.’ He looked up and just then the guy in front of him who was walking point dropped to the ground and an NVA sniper shot Ross in the chest. I ran out and was holding him in my arms and I said, ‘You’re going to make it.’ I stuck my thumb in his chest to try to stop the bleeding and I realized half his back was gone. He choked to death on his own blood. It was stupid of me to run to him because the sniper was still out there—the medic wouldn’t go. I remember punching the medic for not going. I held Ross in my arms while he bled to death. I felt a little guilty and later I left a letter to him at the Wall in Washington because I’d lied when I told him he’d make it and that the helicopters were coming. I thought if I hadn’t called out to him he might have seen the sniper. It bothered me to watch the life run out of him.

We had a lieutenant who was a West Point graduate. He’d been out in the field for six months, and typically they’d give them a job in a base camp for the remainder of their tour but he volunteered to come back out. One day he took his Radio Telephone Operator and said, ‘I’m going to check out this trail.’ We knew better than to walk the trails. This RTO came running back a few minutes later and said they’d captured the lieutenant. We found him three days later. They had buried him up to his neck. They’d peeled all the skin off his face and shot him through the head. We thought, “Man these people are cruel!” We had to change all the call signs and maps because he’d had all that stuff on him…

I was in country for three months and we hit this bunker complex. There was a ten-fifteen-minute firefight. After it was over this woman came out of a hole in the back of a bunker. She stood on top of the bunker; she was pregnant. She said, “Chieu hoi,” which means ‘I surrender.’ This guy with a machine gun said, ‘Chieu hoi, my ass!’ and hit her with a burst of M16 fire. She fell backwards and the guy took a knife and cut her stomach open, took out the baby and drop-kicked it like a football. And he said, “Well, I got two for the body count.” I couldn’t believe it—I was shocked to see this.

This guy was in country for eight or ten months and somebody was smoking dope in the rear and he reported him. It was at Blackhorse. The next day they found him hanging in the showers. He was beaten to death, I remember thinking, ‘That’s what he deserves for killing that woman.’…

I have nightmares every night. When I first came home I drank so much trying to block everything out. It wasn’t until I quit drinking that I started having flashbacks of incidents that happened to me in Vietnam. For a long time I’d have flashbacks every time I heard a helicopter. I remember when they dedicated the Vietnam Memorial in Cincinnati, three helicopters flew in and one came in really low. The next thing I know I’m crawling on the ground.

I’ve been in group therapy for combat veterans since 1980. When I came back from Vietnam I had jobs. My coworkers would do stuff to aggravate me. They’d come up behind me and drop skids to watch me jump. I tried to kill a guy at work one day. My doctor told me, “You can’t work any more. You have to go on disability.”

I’ve learned with PTSD what you can do and what you can’t do. I was feeling depressed a few years ago. I sat on the toilet and put this SKS assault rifle under my chin, pulled the trigger, and it went ‘click.’ My wife came in. I looked at her, she looked at me, and I said, “Shit! It didn’t go off. It must not be my time.”

____________

Jeff Wolins website

Jeff Wolin’s interview of Medic

War Talk, American

In 2008 Medic met the distinguished photographer Jeff Wolin, then working on his book Inconvenient Stories: Vietnam Veterans. Jeff has kindly lent permission to excerpt several of those stories and their accompanying photographs.

173rd Air Borne, PFC

May 1965-1966;

1966-1967; 1968

“The first time I saw a dead American, there were three of them-their heads were up on stakes. It was in ‘D’ zone, not too far from Bien Hoa. The enemy was doing that to scare us. Of course, it didn’t scare us; it made us angry. It made me angry. By this time I was lost in the jungle. I was alone. I was AWOL-I weighed 112 pounds; they wanted me to hump a spare barrel of an M60 machine gun. I had just gotten out of the hospital two weeks before with appendicitis. I’m thinking, ‘I’m not in shape. I can’t do this job. I’m leaving!’

I ran off and then I stopped. ‘What in the hell are you doing? You’ve never been in the jungle before!’ By this time it was too late. I was lost, separated from my unit. That’s when I ran across the heads. I found the individuals that did it. I heard them down the hill by the river and there was one over where the heads were and he was masturbating. I was going to try to take him prisoner but I stumbled and I stabbed him accidentally with the bayonet. Once I did that I had to kill him. And when the other two came up I shot them both and I cut off their heads. Some of the guys from the 101st Airborne used to call me ‘headhunter.’

At first I did it because I was enraged but then it was a way to score points-that’s how you were esteemed by your peers. It didn’t bother me back then. But now I don’t sleep more than 15-20 minutes at a time and then I wake up with nightmares and chills and sweats. I walk the perimeter at night. But that’s my cross to bear. I see children when you’ve killed their parents-you hear them crying.

I proudly endured that I stood my post; I did what was expected of me. My fellow paratroopers respected me despite the fact that I was a fuck-up in the rear. In the boonies I did my job. Today I have to suffer with that. No big deal. Thank you very much for your tax dollars-the VA pays for it. Georgie-boy, when he came in as president, they started cutting our benefits. I’m at 150% disability: 100% for PTSD; 30% for diabetes; 10% for erectile dysfunction and 10% for organic brain damage. I’m in pain all the time but you get used to it. They give me medication but it doesn’t work. What does help is marijuana but the sons of bitches won’t let me have it. I don’t want no more drugs. They want to give me codeine, heavy narcotics, but that counteracts the Viagra and I’d rather have a hard-on and endure the pain than just be a fucking zombie…

Here we are in the middle of the night-it’s drizzling-me, Doc Wheatfield, a guy we called Cherry, John Wekerly, and some others. We go and there’s a girl lying under a huge banyan tree. The only other one there is a little boy. She’s pregnant, about to deliver a baby. We break out our ponchos and Doc Wheatfield gets underneath and delivers the baby. We felt responsible for the baby. Doc asks one of the guys to get some fruit from the C-rations. I said, ‘Doc, no one’s going to give up their fruit.’ Doc was a Christian man. He said, ‘Oh, ye of little faith.’

The guys came back with a big sack full of canned fruits. We gave her whatever we had in money and fruit. And then a mama-san arrived and first she looked at us real mean like ‘you murdering bastards.’ But then she saw the food, money, the baby was fine, the little shelter we had built and she came and stood in front of us and she bowed.

It was raining, like I said, but when the baby came out there was a clap of thunder and it stopped raining and the baby cried out. You could hear it in the whole valley. We were so proud and so happy and some of us were crying. As soon as we started to leave, here comes the rain again. We were walking along a rice paddy, standing out like a sore thumb if there was a sniper on the hill, especially when the lightning flashed. There was a herd of water buffalo and someone says, ‘Look at that deformed cow!’ It was a cow having a calf. People from ranches will tell you this: a bull knows its babies and will allow the mother to have a calf but other bulls don’t give a damn. So here we are in the middle of the rain holding hands in a circle around this cow while Doc Wheatfield is helping deliver that calf.

We went over there as regular kids doing a tough job. Some of us lost our way. We did bad things when we were required to but at the same time when it came to helping the innocent, we helped. We were noble. Our hearts were good and those good hearts got wounded.

After the war we were treated disrespectfully. We were persecuted. In the ’70’s over 30% of federal prison inmates were Vietnam veterans. I was one of them. On Mother’s Day, my father, Benito Garcia, a police officer, arrested me for robbing banks. In 18 days I robbed 6 banks in Chicago. I’d go in with a .25 automatic pistol with .22 ammunition-I didn’t even have a gun that shot. I was not very good at it. Then I hung up my guns and picked up the books while in prison. In 16 months I received my Associates degree in Secondary Education from Vincennes University. I earned enough credits for a Bachelors degree from Indiana University in Sociology.

In prison I felt comfortable because I know how to be in a society of macho men. I was always alert, always tense. I could deal with that environment-it was the jungle with steel bars. I could function there; I couldn’t function out here-it’s still difficult. I served 6 years, 1 week active military service and 6 years, 3 months in prison. I got my degree; I was released and I was everybody’s success story. Harry Porterfield did a 30 minute segment on me for the CBS Chicago affiliate.

I was successful for a while but then the nightmares about ‘Nam started and I had to drink. The only way I can get through the night without getting up is when I’m passed-out drunk. But I haven’t had a drink since ’95 when I got in trouble again. An east Texas judge wouldn’t believe that I was a thrifty shopper and that the 320 pounds of marijuana in the trunk were all for me. I wound up in a Texas prison. I served 3 years, 3 months. I am presently on parole for that offense-possession of marijuana, not distribution. When I got out I had 89 months of parole-I’ve got 14 months left. I successfully completed the parole for my bank robberies and I expect to successfully finish this one. I won’t smoke now, but come December 27, 2005, I am going to roll a fucking joint the size of a bus and I’ll kill it in one drag.”

R. Michael Rosensweig

U. S. Army Rangers Specialist E-4

1969-1971

“After my first tour of duty in Vietnam I had orders for Fort Bragg. I got back to the states and at that time my family was in Baltimore. I was walking up Howard Street in downtown Baltimore—I was still in uniform. A truck backfired about two blocks behind me. I just yelled, ‘Incoming!’ and hit the pavement. It just freaked everybody out. I said, ‘To hell with this.’ Next morning I took the bus, went down to the Pentagon and had orders changed to go back to ‘Nam—just wasn’t ready to come back to what we like to call ‘civilization.’ I wasn’t done fighting my war—there was still a cause to be fought for.

I enjoyed the combat—the adrenalin. Don’t mistake that. Don’t mistake the love of combat for the lack of fear. We were all scared—just some of us got off on the adrenaline…

As far as getting orders changed, it was no problem. I just went down there, told them I wanted a change to go back to ‘Nam. Eighteen days later I was back in country. I went through Rangers school—we had our own school in Vietnam. It was ten days of sheer hell. Our training was geared to guerilla fighting. I was stationed in the same area as my first tour, Central Highlands. The company was based in An Khe.

I loved being with the Rangers. We were a six-man hunter-killer team. Our mission was to go out and kill. Go in, strike, get out—covert. Sometimes if there were too many NVA we had to call in air strikes. Sometimes we had to call them in a lot closer than was allowed by military regs. In some cases it was do that or die anyway.

War just leaves scars that will never heal up in your head because of the overall trauma. The first person I ever had to kill was an eight-year old boy. We were escorting the 101st Airborne in the A Shau Valley. A little boy ran out of the village with a grenade in his hand heading straight for a truckload of GI’s—kind of hard to balance that one out. The grenade was in his hand. We tried to get him to stop—‘Dong Lai!’ ‘Stop!’ He just kept running with that Chi Com in his hand—it’s a Chinese Communist grenade with a string fuse. We didn’t have a choice. If we hadn’t killed him he would have ended up throwing it in a truckload of GI’s. He was about 25 yards away. There are too many other instances like this to list and I say that in all sincerity. I just can’t talk about them.

They deactivated my company just a few months after I left when they started the withdrawal. A lot of guys who stayed went to either Special Forces or went to work for the CIA as black ops in Cambodia. The time I served with the Rangers was the pinnacle of everything I’d ever wanted to be. And when I lost that, I couldn’t see past the war.

They sent me to Germany to an artillery unit as a mechanic and four months later I was out. A couple of Puerto Rican guys from New York were having some kind of big war among themselves and they made the mistake of coming through my room in the middle of the night. You don’t just take somebody fresh out of combat and startle him in the middle of the night because he ain’t going to hide his head under the covers—he’s coming out attacking. And that’s what I did. The first I threw out the window; the other I pinned up against a locker and stuck a bayonet right up against his throat. I almost killed two of our guys—four months later I was out. There’s a lot of stuff especially with the Rangers that’s still classified and I can’t talk about.

I have plenty of firepower. I stay pretty heavily armed at home and everybody that knows me knows better than just to drop in—I’m in my bunker. The woman I was married to for fourteen years was scared to death of me the whole time we were married because of the nightmares—wake up in the middle of the night crying, screaming, roaming around.

You know, because of my background in Vietnam, we had to watch our tempers more than anyone else. Society did not give us the right to get angry and shout. If we did that we were considered lethal. I got fired more than once just for doing nothing more than anybody else would have done—got mad at somebody for doing something really stupid. Yelled at him. The reason I was given was because when I get mad, all people see in my eyes is death.”

25th Infantry Division

APC Driver 1967-1968

“On New Year’s Eve we started getting radio messages from LP’s in the woods-three-man listening posts, ‘Something’s happening! Something’s happening! Something’s happening!’ The fighting started about 11 o’clock at night and went steady, on and off, until the next morning, until it got light enough to see-then it stopped.

I will never forget this. I know I didn’t dream it. I haven’t imagined it. The sun came up and the smoke cleared and the dew burned off. There was meat all over everything. All around the perimeter it was meat. And the wood line, which was maybe fifteen or twenty meters away looked like ruined drapes. It was a mess.

One thing that Oliver Stone, who described this battle in Platoon, got right-at the end of the firefight in the film the planes come in and drop napalm, which didn’t happen; they didn’t drop anything on us. The next morning when the kid wakes up there’s white powder all over everything. Everything sort of looked antique-I remember that distinctly. It was dust and junk all over everything. Everybody was covered with dust and sweat. And the bodies and the body parts, the meat, looked antique. Not fun. I never want to go through something like that ever again.

One of the things I did at the beginning of the battle: my track had been on the perimeter and then they moved us to a new spot on the perimeter. I parked the track in such a way that the gas tank was as far away from a direct shot as possible. There were some tracks that got blown up and burned to the ground. The gasoline fire melted the metal armor-around a couple of the tracks you’d have this huge puddle of aluminum alloy. One of the tracks in our platoon got hit and burned and the driver’s body was simply incinerated. All we found of him was a bit of his backbone, his pelvis and his skull.

As drivers we were sitting in the track from the neck down so you can see; everyone else is sitting on top. If an RPG hit the track, the driver has the gas tank right behind and the drivers always got fucked. If I ever meet the bonehead who sent gasoline powered Armored Personnel Carriers to Vietnam instead of diesel, which is less flammable, he and I are going to have a real serious conversation. I would gladly do time in prison for the privilege of beating the shit out of the guy…

It’s a true fact if ever there was: I became a writer because of the war and not the other way around. It’s one of the great ironies of my life and it’s an irony I share with a number of writers who came out of Vietnam. Bruce Weigl would be working in a mill around Lorain, Ohio. Probably the only writer I know who would have been a writer regardless of the war is Robert Olen Butler.

My old man drove a bus and had four sons. Word in the house was: finish high school and get a job. I’m the only one of the brothers who finished college. Becoming a writer was the farthest thing from my mind. I came back from Vietnam in early spring of 1968. Three weeks later Martin Luther King was murdered. Then in June, Bobby Kennedy was murdered. I got a job that summer driving a Chicago city bus and literally drove through the big doings at the Democratic National Convention in August. I thought the war had followed me home.

I wanted to go back to school. I took a writing class because I thought it was going to be a snap ‘A’ and I wouldn’t have to work. I got fooled. The second night of class the teacher comes up to me and says, ‘If you want to write war stories, here, read these two books.’ And he hands me The Iliad and War and Peace; it took a year to read those books. The Iliad is a paradigm for a lot of things but it’s a war story so it’s a paradigm for war stories.

I became a writer because I had a story that would not be denied. I was talking about this the other day with my editor and I said, ‘For 35 years I’ve been thinking about the war every day.’ The war had a tremendous impact on my life. When my kids were old enough I had to teach them not to come up behind me and give me a hug around my throat. Don’t make a loud, sudden noise behind me. I’ve always had a kind of tic and I went to the VA and the shrink said it was some kind of seizure. It’s a flashback. It only lasts an instant but you get a full image of an event.

As a writer Vietnam is my subject. Faulkner had Yoknapatawpha County and he had that in his head all his life. All he had to do was dip in this story or that story and the characters were all right there. Garrison Keillor had Lake Wobegone-what a remarkable discovery! I used to be embarrassed to write about the war-not so much now. I’ve been blessed with a source. I know for a fact that as a writer I can reach around and touch the war and always find a story. The war really did give me something that I love-writing is a craft that I love.”

Medic’s friend, and a friend to many who knew or studied with him, Larry Heinemann died on 12 December 2019. He will be deeply missed.

U.S. Army Specialist E-5

1968-1969

“Everybody was real tight in my platoon—we were like a brotherhood in the field. There were a lot of dudes we called the ‘blue-eyed souls’. They realized, ‘Hey we’re all over here together. We should be sticking together.’ These were the white guys who didn’t mind walking with the brothers because the brothers got together over there. The only racial problems were back in the rear with the punks with the gear. We’d come in from the field to the base at Pleiku. They wanted us to give up our guns so we stayed in the motor pool with our tanks—told them we were part of the ‘quick reaction force.’

I remember this one particular time, me and a bunch of the guys walked into a bar on the base. There were these guys sitting there in new fatigues and shined boots and looked like they ain’t never been out in the sun. And it was generally like that. The majority of the guys in the rear with the gear were white. And one of them said, ‘Here come a bunch of them damn boonie rats.’ Another said, ‘Yeah, boonie rats, niggers. It’s the same.’ You know, stuff like that. We just walked by.

It was an enlisted mens club. I would roll up my sleeves so my E-5 rank would not show and I could go in with my buddies, because the majority of my buddies were E-4 and below. And I didn’t like going into those clubs where they only played country western. Plus this club had the best entertainment: Philippine girls singing like Diana Ross: ‘Stop in the name of love.’ Everybody was going, ‘Yeah! Sounds like Diana.’

But we was in there and I’ll never forget that night because those guys were throwing beer cans at us. About ten beer cans came flying over from them chumps and we still said, ‘Hey, man, let it go.’ Everybody got a frag grenade in their pocket. It kept going and eventually the place started to close so everybody was talking and I said, ‘Hey, man, let’s just go out and deal with this right now.’ I’m thinking my buddies heard me. So I walk out of the club all bad and this little short guy, kind of bald-headed, said, ‘Yeah, that’s right, nigger!’

And man, I punched him upside his face and was working him over. I picked him up; I had him down. I felt kicks in the back of my head—apparently my boys didn’t hear the word; it was just me out there on the ground. All of a sudden it felt like an earthquake, like a stampede and then the fight really broke out—those crazy dudes from the tanks were ready. They were tearing up folk, man. And I remember grabbing that little guy by his leg and dragging him out of the mess so I could work him over some more. That was funny, man. I hope that guy’s doing ok today.

The MP’s came and we all started running. We didn’t know our way around base camp. I remember falling in these drainage ditches because there was so much rain up there in the Central Highlands in the monsoons. And man, I remember falling into ditch after ditch. Nobody got caught; we all got back. We laughed about it…

After I got home to East Texas, me and Ray, a Vietnam vet buddy of mine, went to pick up the money the Army owed us. We were so happy. We’d been all over the world. I was based in Germany, man. I didn’t go out on the town for a year. I couldn’t. When people asked me, I said, ‘No, man. Where I come from you don’t do that with white folks.’ For a whole year me and the Playboy bunnies had an intimate relationship. But after going home to Texas on Christmas leave and finding my first love in the arms of another man—after I had been so true to her for a whole year—I was numb. So I finally went downtown in Erlangen, Germany; I was making up for lost time. I met a woman named Heidi, which was a blessing. Then I was in Vietnam for a year. There was a thing among African Americans: my father and every generation going back fought for our country in whatever war was going on.

Anyway, me and Ray drove over to Fort Polk, Louisiana to get our money. There was a little club on the way back where we wanted to stop and have a beer. We walked in this place and the guy said, ‘We don’t serve niggers here.’ I looked at Ray and he looked at me. He said, ‘Did he say what I thought he said?’ I said, ‘Yeah, he did, Ray.’ He said, ‘All right, let’s go.’ Can you imagine? I’d been all over the world and everywhere I was a man except when I came back to America.”

U.S. Navy Physician Lieutenant

1968-1969

We docs had a lot of resentment being taken away from training and going to a war we didn’t believe in, but the saving grace for us was that we weren’t going to fight or kill anyone—we were going to treat sick people. And so you tried to erase everything else from your mind except, “I might as well be a doctor over there as a doctor over here.” Time has taught us that physicians who take part in a war are much better surgeons and physicians because you learn to react instantaneously without scratching your head. That kind of training is invaluable. I trained at Los Angeles County Hospital, which is its own Vietnam with the gang wars and all. So I was used to that kind of pace.

You could forget about the war because your concentration was on patients, until those times when the fighting stopped, until you go into periods where you had to deal with the guys falling apart emotionally. When they weren’t having to go out and shoot, they just had to sit back and look at what was happening, make a count of how many friends they had left and wonder what was going to happen next.

Vietnam was a war with no front. The front was underneath you; it was behind you; it was beside you. The method of survival in Vietnam was for the Vietnamese to be dedicated to the U.S. troops during the day because we were fighting North Vietnam, but the Viet Cong were so embedded in the country that even though they had a different allegiance, they were so threatened that the South Vietnamese who worked for us worked for the VC at night. Someone could be very devoted to you as a doctor—your private nurse, or your house mouse, the women who came and cleaned and kept our boots free of snakes—but at night they might get orders that they had to go in and destroy us.

We had an instance where a couple of Vietnamese nurses who worked for us burrowed into one of our bunker hospitals one night and opened fire killing all twenty-six patients that they’d been treating plus three of the corpsmen. One of these was a brilliant surgical nurse. She was captured by the Marines the next day. It was discovered what she had done and so the Marines tied her to two helicopters that took off and pulled her body apart.

It was hideous conceptually, and it was deplorable but when you were fresh from what just happened, it was difficult to admit that you almost had a feeling that that was ‘okay.’ Once you got some distance from it, you knew what pressure she was under so that you got the guilts for ‘participating.’ We’ve all heard the stories about My Lai and Lt. Calley and about Abu Ghraib in Iraq. Unless you’ve actually been in that situation, it’s hard to imagine man’s inhumanity to man. When you’re in the middle of it, sadly, it somehow doesn’t seem so heinous, so inhuman. It’s only upon reflection that you then absorb part of the guilt of what I think this whole nation has for what we did to Vietnam.

One of the things that was most difficult to deal with was the number of guys who had self-inflicted wounds trying to stay out of the field. We had a kid come in—it was back on the hospital ship. He was just one medevac, one grunt, probably only seventeen, underage for the military, a sweet kid. He was going to be sent up the Cua Viet River into a situation where it was guaranteed, being so low on the totem pole, that he was going to be killed. And he was so terrified about it that he decided to shoot himself. What he wanted to do was simply shoot his toe off but he missed and got his ankle instead. They brought him in on a chopper in the middle of the night. He was in such denial. He said, “I’m not going to go up that river. Don’t cut my fucking foot off!”

I said to him, “There’s no foot to come off. It’s already off.” And he said, ‘I won’t stay here any longer. I did it myself.’ I tried to rationalize with him. “Whatever the shot was that did this, your foot is not there.” Finally, one of the corpsmen raised his bootless leg up and showed him his foot was gone. Then the stunned kid turned his story around and said he stepped on a mine—he would be court-martialed if he shot it off himself. I tried to never find out how that was dealt with by the authorities.

It happened frequently. Guys would stab themselves in the hand or refuse to soak their feet in the saltwater baths so their jungle rot would get really bad—anything to stay out of the field. The guys would confide in you because they didn’t look at us as ‘military’—it was a doctor/patient relationship. They knew I wasn’t going to report them; I never reported anything like that. I was very against what was going on and I wasn’t about to turn a kid in who was so desperate that he would do something like that to himself. What human being would?

As a doctor you had to commit to two years of military service. If your first year was in Vietnam, you could choose anyplace in the U.S. for your second year. I’d always wanted to live in New England so I was assigned to the Fargo Building, the Marine Corps Brig in Boston, which is down by Jimmy’s Harborside Restaurant. I couldn’t afford to live close to that. I lived in a little village, Newton Upper Falls above Wellesley—beautiful countryside. I chose it because it would show all four seasons, and maybe that would let me have a year of purging everything.

The first time I drove to work—I had a new VW Squareback and I was in uniform—I took a shortcut to go through Harvard Yard. I’d never been to Harvard and I wanted to see what it looked like. When the students saw my uniform on campus, they pulled me out and beat me up. I somehow got back to the car and drove to my station. I ran into the commanding officer. I didn’t look very good and I told him what happened. He said, ‘Never wear your uniform off base.’ And I said, ‘With all due respect, I’m not going to wear my uniform this year at all.’ So I didn’t.

And you know, now with a little bit of hindsight and a lot of time passing, I can understand that it wasn’t me being attacked, it was the idea of the uniform and people being against the war. They had no idea that I was a doctor. I represented the ugly other that everybody hated. So that’s what they were beating up. They weren’t beating up Grady, a doctor, who had been in Vietnam basically as a civilian. But it gave all of us who’d been through the war a really different outlook on protesters. Even though I protested the war, I fell victim to what protesters can do and that’s emotionally intolerable.”

U. S. Army Specialist E-4

1969-1970

I think it was July 3. We just came in on a three-day stand-down when they came to us about 8:00 at night. “Get ready to go. We’re going to send you out—there’s movement in the area. We think they’re building a base camp and we want you to check it out.”

So we went out that night and set out at the bottom of a hill and started up. Delta Company was on the other side and they walked into a horseshoe-shaped, battalion-size NVA base camp. It cut them to pieces. The NVA opened up with automatic weapons fire. I got behind a log. Every time I’d raise my head to look out, someone with an automatic would open up. I’m lying there thinking, ‘They’re going to walk up and shoot me in the head.’

You could hear guys hollering for the medics. The NVA had gotten in between my unit and had gotten people’s dog tags and called out their names saying they’d surrendered. An NVA called, ‘Medic, medic!’ and when the medic got there he got shot in the face.

Once we took the hill we found no NVA soldiers—not one dead body. There were GI’s all over the place. They put us on a detail picking up the bodies—take a poncho, roll the guy in the poncho, drag him down the hill. I don’t know how many of our guys we dragged down. I couldn’t look at them any more. It really bothered me. I was thinking, ‘I could be dead too.’…

I lost a friend named Ross. A week before he was killed, he and two other guys came across four or five NVA soldiers eating. Instead of shooting them they got into hand-to-hand combat and killed the NVA. They were decorated. I thought he was really brave.

We were in a firebase and it was morning when I saw him approaching the base. I was standing on a bunker and I yelled out, ‘Hey, Ross, come on; I’ll buy you a beer.’ He looked up and just then the guy in front of him who was walking point dropped to the ground and an NVA sniper shot Ross in the chest. I ran out and was holding him in my arms and I said, ‘You’re going to make it.’ I stuck my thumb in his chest to try to stop the bleeding and I realized half his back was gone. He choked to death on his own blood. It was stupid of me to run to him because the sniper was still out there—the medic wouldn’t go. I remember punching the medic for not going. I held Ross in my arms while he bled to death. I felt a little guilty and later I left a letter to him at the Wall in Washington because I’d lied when I told him he’d make it and that the helicopters were coming. I thought if I hadn’t called out to him he might have seen the sniper. It bothered me to watch the life run out of him.

We had a lieutenant who was a West Point graduate. He’d been out in the field for six months, and typically they’d give them a job in a base camp for the remainder of their tour but he volunteered to come back out. One day he took his Radio Telephone Operator and said, ‘I’m going to check out this trail.’ We knew better than to walk the trails. This RTO came running back a few minutes later and said they’d captured the lieutenant. We found him three days later. They had buried him up to his neck. They’d peeled all the skin off his face and shot him through the head. We thought, “Man these people are cruel!” We had to change all the call signs and maps because he’d had all that stuff on him…

I was in country for three months and we hit this bunker complex. There was a ten-fifteen-minute firefight. After it was over this woman came out of a hole in the back of a bunker. She stood on top of the bunker; she was pregnant. She said, “Chieu hoi,” which means ‘I surrender.’ This guy with a machine gun said, ‘Chieu hoi, my ass!’ and hit her with a burst of M16 fire. She fell backwards and the guy took a knife and cut her stomach open, took out the baby and drop-kicked it like a football. And he said, “Well, I got two for the body count.” I couldn’t believe it—I was shocked to see this.

This guy was in country for eight or ten months and somebody was smoking dope in the rear and he reported him. It was at Blackhorse. The next day they found him hanging in the showers. He was beaten to death, I remember thinking, ‘That’s what he deserves for killing that woman.’…

I have nightmares every night. When I first came home I drank so much trying to block everything out. It wasn’t until I quit drinking that I started having flashbacks of incidents that happened to me in Vietnam. For a long time I’d have flashbacks every time I heard a helicopter. I remember when they dedicated the Vietnam Memorial in Cincinnati, three helicopters flew in and one came in really low. The next thing I know I’m crawling on the ground.

I’ve been in group therapy for combat veterans since 1980. When I came back from Vietnam I had jobs. My coworkers would do stuff to aggravate me. They’d come up behind me and drop skids to watch me jump. I tried to kill a guy at work one day. My doctor told me, “You can’t work any more. You have to go on disability.”

I’ve learned with PTSD what you can do and what you can’t do. I was feeling depressed a few years ago. I sat on the toilet and put this SKS assault rifle under my chin, pulled the trigger, and it went ‘click.’ My wife came in. I looked at her, she looked at me, and I said, “Shit! It didn’t go off. It must not be my time.”

____________

Jeff Wolins website

Jeff Wolin’s interview of Medic