by Richard Boes

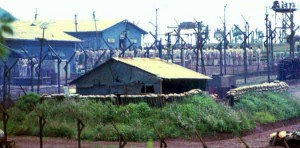

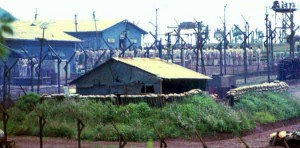

I was trained as an MP and had been assigned to th e First Cavalry in ’69-’70. We were stationed on a small base camp on the outskirts of a Vietnamese village near Bien Hoa. Our POW compound was surrounded by twenty-foot high barbed wire. The prisoners, who never had names, were kept beneath open tents, with bare cots to sleep on. There was a pallet of board under each cot to keep it from sinking into the mud. We as guards had bunkers made with empty oil drums, three-fourths of which were sunken into the ground. Fearing rockets and mortars, I spent many nights peering out from behind an oil drum, my shotgun held on a sleeping prisoner.

e First Cavalry in ’69-’70. We were stationed on a small base camp on the outskirts of a Vietnamese village near Bien Hoa. Our POW compound was surrounded by twenty-foot high barbed wire. The prisoners, who never had names, were kept beneath open tents, with bare cots to sleep on. There was a pallet of board under each cot to keep it from sinking into the mud. We as guards had bunkers made with empty oil drums, three-fourths of which were sunken into the ground. Fearing rockets and mortars, I spent many nights peering out from behind an oil drum, my shotgun held on a sleeping prisoner.

At our POW compound prisoners never stayed very long. They were brought in from the field, interrogated for three or four days, and sent to who knows where. We never had more than three or four at a time. I believe most prisoners never made it out of the field; I think the grunts kept a few alive to see what, if any, information they could get out of the NVA or VC. Some were turned over to the ARVN, the South Vietnamese Army, and I know of at least one who was butchered and strung up for days in the village marketplace as an example to the villagers. The smells and images are still with me.

Prisoners were never dressed in more than a pair of filthy boxer shorts; their legs and feet were often covered with abscessed and oozing heat sores and blisters. I remember thinking they might not feel too bad about being caught, relieved they didn’t have to hump the bush anymore, and grateful to get something more than rice to eat. But I remember only one prisoner receiving medical attention.

Prisoners were never dressed in more than a pair of filthy boxer shorts; their legs and feet were often covered with abscessed and oozing heat sores and blisters. I remember thinking they might not feel too bad about being caught, relieved they didn’t have to hump the bush anymore, and grateful to get something more than rice to eat. But I remember only one prisoner receiving medical attention.

This prisoner, who had been shot in his leg, was interrogated for three days before being taken to the hospital. I provided an escort. At our compound, medevac patients were selected in accordance with the severity of their wounds. One GI with his arm in a cast was bumped from the flight because of my prisoner. He got real pissed. “I gotta wait because of a fucking gook bastard? I’ll kill the motherfucker!”

I tried to calm him. “He’s had a bullet in his leg for three days,” I said.

“Fuck him.”

“Sorry,” I said.

That chopper ride was the worst flight I ever had, and we weren’t even shot at. One of the passengers was an American soldier who had fallen some fifty feet off a radio tower. He was screaming in pain and cursing at the top of his lungs. His feet looked like blue balloons. The ride seemed an eternity, but I don’t recall my prisoner making a sound, showing any emotion or any sign of being in pain. Truth is, I saw more GIs killed by accidents, mistakes, and “friendly fire” than I did by the Viet Cong or NVA. I did get the prisoner to the hospital in one piece, despite numerous requests to fuck him up or boot him out of the chopper.

One of my duties was to monitor interrogations, to make sure the Geneva Convention for the treatment of prisoners was upheld — in reality a joke. A South Vietnamese interpreter would sit facing the prisoner, right in his face. An American intelligence officer sat behind a small table making notes and looking at maps. He spoke through the interpreter, whose translation always seemed longer and more violent. I would stand a few feet off to the side, the official witness to the event.

Prisoners were screamed at, smacked in the face, punched, kicked, spit on; had their hair pulled, their sores and heat  blisters pinched, and their bare feet stomped. One prisoner was made to sit with his legs spread and was repeatedly smacked back and forth on his inner thighs with a ping-pong paddle, making his heat sores bleed. I warned the interpreter once, and then took the paddle from his hand mid-swing. He protested, cursing me in Vietnamese. The intelligence officer stressed the need to obtain information in order to save American lives. He told me that if I had a problem, he’d talk to the colonel and have me relieved of post. I was confused, torn. I gave the interpreter back his paddle.

blisters pinched, and their bare feet stomped. One prisoner was made to sit with his legs spread and was repeatedly smacked back and forth on his inner thighs with a ping-pong paddle, making his heat sores bleed. I warned the interpreter once, and then took the paddle from his hand mid-swing. He protested, cursing me in Vietnamese. The intelligence officer stressed the need to obtain information in order to save American lives. He told me that if I had a problem, he’d talk to the colonel and have me relieved of post. I was confused, torn. I gave the interpreter back his paddle.

One big problem was that we didn’t know the enemy. The Vietnamese employed on the base came from the village. After the work day ended, they went home. One night our barber was shot coming through the perimeter wire. All this time he was VC. There was no one we could trust. Most of us didn’t want to be there. We counted off the days, but the longer I was in Vietnam, the more I became the thing I hated most. This war was about getting out alive, and nothing else mattered.

We treated one prisoner with special care. He wore handcuffs behind his back. Only while he ate would we front-cuff him, then re-cuff him once he finished his meal. He was the enemy’s version of Special Forces, a sapper who could low crawl through barbed wire and trip flares like butter melts on a hot biscuit. Once inside, he would wreak havoc on a base camp with satchel charges and throat-slitting, then disappear into the night. The story was he had surrendered and was working for us as a Kit Carson Scout–a point man leading grunts on patrol. After a time, Intelligence figured out he’d been leaving clues and passing information back to the VC.

We treated one prisoner with special care. He wore handcuffs behind his back. Only while he ate would we front-cuff him, then re-cuff him once he finished his meal. He was the enemy’s version of Special Forces, a sapper who could low crawl through barbed wire and trip flares like butter melts on a hot biscuit. Once inside, he would wreak havoc on a base camp with satchel charges and throat-slitting, then disappear into the night. The story was he had surrendered and was working for us as a Kit Carson Scout–a point man leading grunts on patrol. After a time, Intelligence figured out he’d been leaving clues and passing information back to the VC.

One day this prisoner walked slowly across the POW compound, he looked exhausted: head down, feet dragging. Suddenly, he burst forth like a runner from a starting block, jumped atop a bunker, and did a complete flip over the barbed wire, landing on his feet — all with his hands cuffed behind his back! In broad daylight he didn’t have a prayer of getting away. Two GIs standing thirty feet outside the compound heard my cry for help. They knocked the prisoner to the ground and stomped him into the mud.

At that moment I had my awakening. Seeing this man’s determination, fortitude, and tenacity, I realized I was the enemy; we didn’t belong in Vietnam. After this incident, they put shackles on the POW’s ankles and had a shotgun pointing at him 24/7.

I grew up in a small town, believed in God and the goodness of people, respected adults and thought they knew best. I was proud to be an American. I wanted to do right by my country. I volunteered for Vietnam. But once there, the things I saw done on behalf of my country shattered my dreams.

Medic met Richard at a poetry reading at the Colony Cafe in Woodstock, NY in 2008. He spoke loudly, in a voice that was harsh, friendly, and pleading. A tall man, his arms and legs were thin; his belly protruded abnormally. Richard died in a VA hospital a year later of Agent Orange related cancer. His books include The Last Dead Soldier Left Alive, and Last Train Out. As an actor, Richard had supporting roles in several films by Jim Jarmush, including Night on Earth, Dead Man, and Stranger Than Paradise.

Medic met Richard at a poetry reading at the Colony Cafe in Woodstock, NY in 2008. He spoke loudly, in a voice that was harsh, friendly, and pleading. A tall man, his arms and legs were thin; his belly protruded abnormally. Richard died in a VA hospital a year later of Agent Orange related cancer. His books include The Last Dead Soldier Left Alive, and Last Train Out. As an actor, Richard had supporting roles in several films by Jim Jarmush, including Night on Earth, Dead Man, and Stranger Than Paradise.

VC POWs

by Richard Boes

I was trained as an MP and had been assigned to th e First Cavalry in ’69-’70. We were stationed on a small base camp on the outskirts of a Vietnamese village near Bien Hoa. Our POW compound was surrounded by twenty-foot high barbed wire. The prisoners, who never had names, were kept beneath open tents, with bare cots to sleep on. There was a pallet of board under each cot to keep it from sinking into the mud. We as guards had bunkers made with empty oil drums, three-fourths of which were sunken into the ground. Fearing rockets and mortars, I spent many nights peering out from behind an oil drum, my shotgun held on a sleeping prisoner.

e First Cavalry in ’69-’70. We were stationed on a small base camp on the outskirts of a Vietnamese village near Bien Hoa. Our POW compound was surrounded by twenty-foot high barbed wire. The prisoners, who never had names, were kept beneath open tents, with bare cots to sleep on. There was a pallet of board under each cot to keep it from sinking into the mud. We as guards had bunkers made with empty oil drums, three-fourths of which were sunken into the ground. Fearing rockets and mortars, I spent many nights peering out from behind an oil drum, my shotgun held on a sleeping prisoner.

At our POW compound prisoners never stayed very long. They were brought in from the field, interrogated for three or four days, and sent to who knows where. We never had more than three or four at a time. I believe most prisoners never made it out of the field; I think the grunts kept a few alive to see what, if any, information they could get out of the NVA or VC. Some were turned over to the ARVN, the South Vietnamese Army, and I know of at least one who was butchered and strung up for days in the village marketplace as an example to the villagers. The smells and images are still with me.

This prisoner, who had been shot in his leg, was interrogated for three days before being taken to the hospital. I provided an escort. At our compound, medevac patients were selected in accordance with the severity of their wounds. One GI with his arm in a cast was bumped from the flight because of my prisoner. He got real pissed. “I gotta wait because of a fucking gook bastard? I’ll kill the motherfucker!”

I tried to calm him. “He’s had a bullet in his leg for three days,” I said.

“Fuck him.”

“Sorry,” I said.

That chopper ride was the worst flight I ever had, and we weren’t even shot at. One of the passengers was an American soldier who had fallen some fifty feet off a radio tower. He was screaming in pain and cursing at the top of his lungs. His feet looked like blue balloons. The ride seemed an eternity, but I don’t recall my prisoner making a sound, showing any emotion or any sign of being in pain. Truth is, I saw more GIs killed by accidents, mistakes, and “friendly fire” than I did by the Viet Cong or NVA. I did get the prisoner to the hospital in one piece, despite numerous requests to fuck him up or boot him out of the chopper.

One of my duties was to monitor interrogations, to make sure the Geneva Convention for the treatment of prisoners was upheld — in reality a joke. A South Vietnamese interpreter would sit facing the prisoner, right in his face. An American intelligence officer sat behind a small table making notes and looking at maps. He spoke through the interpreter, whose translation always seemed longer and more violent. I would stand a few feet off to the side, the official witness to the event.

Prisoners were screamed at, smacked in the face, punched, kicked, spit on; had their hair pulled, their sores and heat blisters pinched, and their bare feet stomped. One prisoner was made to sit with his legs spread and was repeatedly smacked back and forth on his inner thighs with a ping-pong paddle, making his heat sores bleed. I warned the interpreter once, and then took the paddle from his hand mid-swing. He protested, cursing me in Vietnamese. The intelligence officer stressed the need to obtain information in order to save American lives. He told me that if I had a problem, he’d talk to the colonel and have me relieved of post. I was confused, torn. I gave the interpreter back his paddle.

blisters pinched, and their bare feet stomped. One prisoner was made to sit with his legs spread and was repeatedly smacked back and forth on his inner thighs with a ping-pong paddle, making his heat sores bleed. I warned the interpreter once, and then took the paddle from his hand mid-swing. He protested, cursing me in Vietnamese. The intelligence officer stressed the need to obtain information in order to save American lives. He told me that if I had a problem, he’d talk to the colonel and have me relieved of post. I was confused, torn. I gave the interpreter back his paddle.

One big problem was that we didn’t know the enemy. The Vietnamese employed on the base came from the village. After the work day ended, they went home. One night our barber was shot coming through the perimeter wire. All this time he was VC. There was no one we could trust. Most of us didn’t want to be there. We counted off the days, but the longer I was in Vietnam, the more I became the thing I hated most. This war was about getting out alive, and nothing else mattered.

One day this prisoner walked slowly across the POW compound, he looked exhausted: head down, feet dragging. Suddenly, he burst forth like a runner from a starting block, jumped atop a bunker, and did a complete flip over the barbed wire, landing on his feet — all with his hands cuffed behind his back! In broad daylight he didn’t have a prayer of getting away. Two GIs standing thirty feet outside the compound heard my cry for help. They knocked the prisoner to the ground and stomped him into the mud.

At that moment I had my awakening. Seeing this man’s determination, fortitude, and tenacity, I realized I was the enemy; we didn’t belong in Vietnam. After this incident, they put shackles on the POW’s ankles and had a shotgun pointing at him 24/7.

I grew up in a small town, believed in God and the goodness of people, respected adults and thought they knew best. I was proud to be an American. I wanted to do right by my country. I volunteered for Vietnam. But once there, the things I saw done on behalf of my country shattered my dreams.