After eight months in the bush I say good-bye to my men.

After eight months in the bush I say good-bye to my men.

“Doc, don’t leave us,” they say, “Don’t leave the platoon.”

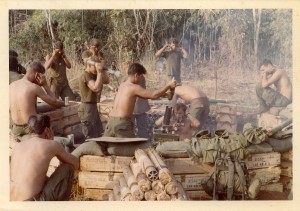

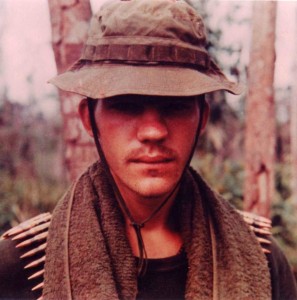

We’ve been through so much. Weeks on end of jungle patrols, ambush or rocket and mortar attacks. A base over run. Or waiting and waiting, the tension rising, and nothing at all. In monsoon we lived and died in mud and rain. In dry season slogged to the beat of our heated thirst. But always took care of each other. I love these men. I always will.

Skinny Bob asks, “You’re not leaving, are you Doc?”

I clamp my jaw tight, crush the tears in my throat. In two months Skinny Bob will be shot dead at close range.

“Where to on R&R?” asks Big Ken, who will die the same day.

“Japan.”

“Then what you gonna do?” asks someone else.

“Got a rear job in Phuoc Vinh,”I manage to say.

“We’ll miss you, Doc. We’ll miss you.”

After handshakes and back slaps and averted eyes, it’s over. I’m finally out of the bush.

In Saigon, boarding a plane in civilian clothes, I feel naked without my rifle, pistol, frags,bug juice, canteens, C-rations, ass wipe. Naked.

I sit next to Spec 4 Samuel Chun, an upbeat, college-educated, Japanese American. He works in an office typing reports. Not once during the six-hour flight does he use foul language.

From the airport near Tokyo we find our way to the Star Hotel.

From the airport near Tokyo we find our way to the Star Hotel.

“Good pussy and good dope,” said Keiffer, a medic in first platoon. “You’ll have a great time.”

Sam is agreeable, or so it seems.

Past the well kept garden, past the white marble Buddha there are endless hallways with furnished rooms but all are dark and empty. Sam and I are the last Americans to visit this war time bordello. The owner, a plump old mama-san, feigns delight.

“Welcome. Welcome,” she says, wiggling the fingers on both her hands.

At her side, Papa-san, a short gaunt man who immediately tells us he fought in World War II. “Ma-chine-gun,” he says, between bursts of smiles.

Mama-san cheerfully leads us to a ghost town of tables and chairs.

“Sit… sit,” she says, pointing to a large black couch facing a deserted bar. She nods politely, then exits through a curtain of colorful glass beads, which continue to clink and rattle as she walks away.

Sam drums his fingertips on his knee. I look about. In this safe well-lit air-conditioned room there is no one on guard. No one breaks squelch twice and whispers, “My sitreps are negative.” No one saying, “Take five,”or “Saddle up.” There is no radio man excitedly shouting into the black plastic handset, “I say again! I say again!” No lieutenant yelling, “Move up ,goddamn it! Move up!” No mortar crews firing harassment rounds. No squirming casualties screaming, “Medic!!…medic!!”

Sam drums his fingertips on his knee. I look about. In this safe well-lit air-conditioned room there is no one on guard. No one breaks squelch twice and whispers, “My sitreps are negative.” No one saying, “Take five,”or “Saddle up.” There is no radio man excitedly shouting into the black plastic handset, “I say again! I say again!” No lieutenant yelling, “Move up ,goddamn it! Move up!” No mortar crews firing harassment rounds. No squirming casualties screaming, “Medic!!…medic!!”

The glass beads rattle; Mama-san shuffles in, a rum and Coke in each hand.

“You pay later,” she says through her painted smile.

The moment we reach for the icy drinks, two young women in short skirts enter the room and sit between us.

Sam turns to me. “May I borrow your camera?” he asks. “I want to see Tokyo.”

The whore seated next to him makes a hurtful face.”GI, you no like?”

Sam presses his lips in apology, takes the camera and waves good bye.

* * *

Her name is Yukio. We sit on the hard square bed in a small square room, surrounded by the simple decor of soap, towel, sink. She is slender, with an ivory face framed by luxuriant black hair. Her bright red lips edge a delicate mouth of crowded white teeth. Her flimsy sweater contains inviting curves which make me hard. But I have fear. I have killed and cared for many men but I’ve never slept with a woman.

Her name is Yukio. We sit on the hard square bed in a small square room, surrounded by the simple decor of soap, towel, sink. She is slender, with an ivory face framed by luxuriant black hair. Her bright red lips edge a delicate mouth of crowded white teeth. Her flimsy sweater contains inviting curves which make me hard. But I have fear. I have killed and cared for many men but I’ve never slept with a woman.

“Can you help me?” I ask her. I pantomime firing my rifle. “Bang! Bang!” You understand?”

My whore nods without mercy.

After the ritual of money, after the time to undress, after she pulls me inside and mechanically rotates her slim ivory hips, she grinds my virginity to pulp.

“Me good fuck, GI” she says, yawning. “Good fuck.”

The next day I take taxis driven by white-gloved drivers, play Pachinko and pinball in noisy arcades, get lost in the sprawling subway, escape from a horde of giggling girls. In a vast teeming mall an army of manikins in a riot of clothes scream, “Buy me! Buy me!”

Another night, another woman. I can’t wait to go back to Vietnam.

On the return flight Sam shows me the photos he’s taken: the city’s immaculate green parks; an ancient stone temple nearly untouched by time; colossal skyscrapers; an entire museum of painted silk.

“Glad you had a good time,” I tell him.

When Sam asks how things went I lie with all my heart.

In Phuoc Vinh the new lieutenant in charge of medics welcomes me to head quarters home–my new home.

In Phuoc Vinh the new lieutenant in charge of medics welcomes me to head quarters home–my new home.

“I don’t know about the bush,” he says, “but back here you will salute officers. You will get your hair cut. You will spit shine your boots.”

Is he out of his mind? I can’t do that. A month later I request to be sent to LZ Green.

“Fine with me, soldier,” says the new lieutenant.

Each morning on the remote base I drag a barrel of shit out from beneath mortar box shitters, pour diesel fuel into the stinking sludge, toss in a trip flare, over the hours, with a long metal stake, stir the burning muck to a fine white ash. At dusk, I drag the barrel back, exchange it for one brimming with shit.

Each day, the gun crews whisper, “How the hell does he do it?”

Who cares what they think? During monsoon burning shit keeps you warm. Keeps you safe. I’ve got three weeks to go in Vietnam. Twenty-one and a wake up, you understand?

A sergeant yells, “Fire Mission!” and immediately the Howitzer crews aim and adjust their cannons, swiftly lift, push, ram the heavy shells home, insert powder bags, slap the hammers at the back of the breech. The cannons roar, the silver shells arc across the sky, fade and disappear. From far away, a rumbling boom.

of the breech. The cannons roar, the silver shells arc across the sky, fade and disappear. From far away, a rumbling boom.

The first sergeant is a tall thin man who has made a career of the Army. “Lifers,” we call them. Some have seen combat, many have not.

“Bravo Company got ambushed,” he says. “They lost a medic. Go out three days. Then I’ll bring you back.”

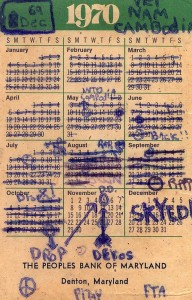

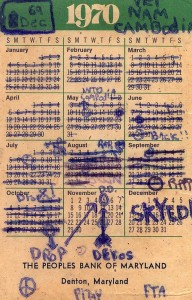

Is he out of his mind? That is not my company. Those are not my men. Fuck Bravo Company. Fuck them all. The days of my life are notched on a cardboard square kept inside a black waterproof wallet, each day one step closer to the rest of my life Eight months in the bush. Half my platoon wounded. Twenty-one and a wake up, you understand?

“No way, Sarge. No fucking way.”

A captain gives a direct order.

I gather my gear, walk to the chopper pad, watch the morning mist rise off the tarmac. There are four new medics in Phuoc Vinh. Why isn’t the new lieutenant sending one to Bravo? Why me? Twenty-one and a wake up. Is he out of his mind? I’m locked and loaded and melting down.

When the chopper swoops in the door gunner yells, “Get on! Get on!” but I shake my head “no.” The pilot snarls at me, but the roar of the engine drowns him out. Ten minutes later a second Huey arrives. “You going to Phuoc Vinh?” The gunner signals thumbs-up. I clamber aboard.

“no.” The pilot snarls at me, but the roar of the engine drowns him out. Ten minutes later a second Huey arrives. “You going to Phuoc Vinh?” The gunner signals thumbs-up. I clamber aboard.

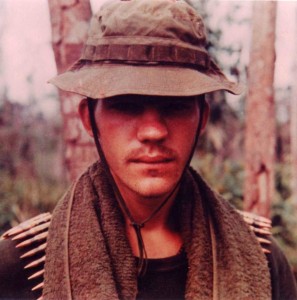

After the short flight I jump out and begin the one-click trudge to the battalion aid station. My pack is loaded with C-rations, medical supplies, a dozen filled one quart canteens. Twenty-one clips in three bandoliers slap my chest with every step. My .45 sits snug in its beat-up leather holster, tied round my leg with a bit of cord taken from a dead VC. Two grenades are neatly hooked to my pistol belt.

Breathing hard, salty sweat dripping down my face, I lean forward, as if on patrol. At a bend in the road I spit at the stray dogs that tag behind me. I’m locked and loaded and melting down.

From fifty meters I spot the new lieutenant as he exits the aid station. He is a handsome, clean shaven man, wearing a clean uniform and polished black boots. He is just then finishing up a smile when he stops mid-stride at the sight of me. Too late. My M16 levels itself at his chest.

Walking toward him I hear a strange voice shouting, “Are you sending me out? You motherfucker! Are you sending me out?”

The lieutenant does not move. Does not speak. Slowly, he raises both hands over his head.

“I’m sorry,” he mutters. He is trembling. “I’ll send someone else.”

I take one step back, lower my weapon, push the safety on, walk past the no-good-rat-fuck-rear-echelon-son-of-a-bitch, saunter into the aid station, push past the astonished new medic who will take my place, find a bunk, throw down my gear, and weep.

He never bothered me again.

_______________________

Two tour 75th Ranger and LRRP pointman Dave Bianchini talks about combat on That Show With Mike Rakosi.

On Meeting the New Lieutenant

“Doc, don’t leave us,” they say, “Don’t leave the platoon.”

We’ve been through so much. Weeks on end of jungle patrols, ambush or rocket and mortar attacks. A base over run. Or waiting and waiting, the tension rising, and nothing at all. In monsoon we lived and died in mud and rain. In dry season slogged to the beat of our heated thirst. But always took care of each other. I love these men. I always will.

Skinny Bob asks, “You’re not leaving, are you Doc?”

I clamp my jaw tight, crush the tears in my throat. In two months Skinny Bob will be shot dead at close range.

“Where to on R&R?” asks Big Ken, who will die the same day.

“Japan.”

“Then what you gonna do?” asks someone else.

“Got a rear job in Phuoc Vinh,”I manage to say.

“We’ll miss you, Doc. We’ll miss you.”

After handshakes and back slaps and averted eyes, it’s over. I’m finally out of the bush.

In Saigon, boarding a plane in civilian clothes, I feel naked without my rifle, pistol, frags,bug juice, canteens, C-rations, ass wipe. Naked.

I sit next to Spec 4 Samuel Chun, an upbeat, college-educated, Japanese American. He works in an office typing reports. Not once during the six-hour flight does he use foul language.

“Good pussy and good dope,” said Keiffer, a medic in first platoon. “You’ll have a great time.”

Sam is agreeable, or so it seems.

Past the well kept garden, past the white marble Buddha there are endless hallways with furnished rooms but all are dark and empty. Sam and I are the last Americans to visit this war time bordello. The owner, a plump old mama-san, feigns delight.

“Welcome. Welcome,” she says, wiggling the fingers on both her hands.

At her side, Papa-san, a short gaunt man who immediately tells us he fought in World War II. “Ma-chine-gun,” he says, between bursts of smiles.

Mama-san cheerfully leads us to a ghost town of tables and chairs.

“Sit… sit,” she says, pointing to a large black couch facing a deserted bar. She nods politely, then exits through a curtain of colorful glass beads, which continue to clink and rattle as she walks away.

The glass beads rattle; Mama-san shuffles in, a rum and Coke in each hand.

“You pay later,” she says through her painted smile.

The moment we reach for the icy drinks, two young women in short skirts enter the room and sit between us.

Sam turns to me. “May I borrow your camera?” he asks. “I want to see Tokyo.”

The whore seated next to him makes a hurtful face.”GI, you no like?”

Sam presses his lips in apology, takes the camera and waves good bye.

* * *

“Can you help me?” I ask her. I pantomime firing my rifle. “Bang! Bang!” You understand?”

My whore nods without mercy.

After the ritual of money, after the time to undress, after she pulls me inside and mechanically rotates her slim ivory hips, she grinds my virginity to pulp.

“Me good fuck, GI” she says, yawning. “Good fuck.”

The next day I take taxis driven by white-gloved drivers, play Pachinko and pinball in noisy arcades, get lost in the sprawling subway, escape from a horde of giggling girls. In a vast teeming mall an army of manikins in a riot of clothes scream, “Buy me! Buy me!”

Another night, another woman. I can’t wait to go back to Vietnam.

On the return flight Sam shows me the photos he’s taken: the city’s immaculate green parks; an ancient stone temple nearly untouched by time; colossal skyscrapers; an entire museum of painted silk.

“Glad you had a good time,” I tell him.

When Sam asks how things went I lie with all my heart.

“I don’t know about the bush,” he says, “but back here you will salute officers. You will get your hair cut. You will spit shine your boots.”

Is he out of his mind? I can’t do that. A month later I request to be sent to LZ Green.

“Fine with me, soldier,” says the new lieutenant.

Each morning on the remote base I drag a barrel of shit out from beneath mortar box shitters, pour diesel fuel into the stinking sludge, toss in a trip flare, over the hours, with a long metal stake, stir the burning muck to a fine white ash. At dusk, I drag the barrel back, exchange it for one brimming with shit.

Each day, the gun crews whisper, “How the hell does he do it?”

Who cares what they think? During monsoon burning shit keeps you warm. Keeps you safe. I’ve got three weeks to go in Vietnam. Twenty-one and a wake up, you understand?

A sergeant yells, “Fire Mission!” and immediately the Howitzer crews aim and adjust their cannons, swiftly lift, push, ram the heavy shells home, insert powder bags, slap the hammers at the back of the breech. The cannons roar, the silver shells arc across the sky, fade and disappear. From far away, a rumbling boom.

of the breech. The cannons roar, the silver shells arc across the sky, fade and disappear. From far away, a rumbling boom.

The first sergeant is a tall thin man who has made a career of the Army. “Lifers,” we call them. Some have seen combat, many have not.

“Bravo Company got ambushed,” he says. “They lost a medic. Go out three days. Then I’ll bring you back.”

Is he out of his mind? That is not my company. Those are not my men. Fuck Bravo Company. Fuck them all. The days of my life are notched on a cardboard square kept inside a black waterproof wallet, each day one step closer to the rest of my life Eight months in the bush. Half my platoon wounded. Twenty-one and a wake up, you understand?

“No way, Sarge. No fucking way.”

A captain gives a direct order.

I gather my gear, walk to the chopper pad, watch the morning mist rise off the tarmac. There are four new medics in Phuoc Vinh. Why isn’t the new lieutenant sending one to Bravo? Why me? Twenty-one and a wake up. Is he out of his mind? I’m locked and loaded and melting down.

When the chopper swoops in the door gunner yells, “Get on! Get on!” but I shake my head “no.” The pilot snarls at me, but the roar of the engine drowns him out. Ten minutes later a second Huey arrives. “You going to Phuoc Vinh?” The gunner signals thumbs-up. I clamber aboard.

“no.” The pilot snarls at me, but the roar of the engine drowns him out. Ten minutes later a second Huey arrives. “You going to Phuoc Vinh?” The gunner signals thumbs-up. I clamber aboard.

After the short flight I jump out and begin the one-click trudge to the battalion aid station. My pack is loaded with C-rations, medical supplies, a dozen filled one quart canteens. Twenty-one clips in three bandoliers slap my chest with every step. My .45 sits snug in its beat-up leather holster, tied round my leg with a bit of cord taken from a dead VC. Two grenades are neatly hooked to my pistol belt.

Breathing hard, salty sweat dripping down my face, I lean forward, as if on patrol. At a bend in the road I spit at the stray dogs that tag behind me. I’m locked and loaded and melting down.

From fifty meters I spot the new lieutenant as he exits the aid station. He is a handsome, clean shaven man, wearing a clean uniform and polished black boots. He is just then finishing up a smile when he stops mid-stride at the sight of me. Too late. My M16 levels itself at his chest.

Walking toward him I hear a strange voice shouting, “Are you sending me out? You motherfucker! Are you sending me out?”

The lieutenant does not move. Does not speak. Slowly, he raises both hands over his head.

“I’m sorry,” he mutters. He is trembling. “I’ll send someone else.”

I take one step back, lower my weapon, push the safety on, walk past the no-good-rat-fuck-rear-echelon-son-of-a-bitch, saunter into the aid station, push past the astonished new medic who will take my place, find a bunk, throw down my gear, and weep.

He never bothered me again.

_______________________

Two tour 75th Ranger and LRRP pointman Dave Bianchini talks about combat on That Show With Mike Rakosi.