In 1987, while living in Astoria, New York, Medic joined CISPES, the Committee in Solidarity to the People of El Salvador, a grass roots organization opposed to US foreign policy in El Salvador. We meet weekly in Manhattan to discuss political developments, fund raising, and civil disobedience. CISPES also joined other grass roots efforts in opposing US foreign wars.

At one such meeting I met Max Grieshaber, a polymath, natural leader, and talented self taught artist. We teamed up to make banners for political demonstrations.

At one such meeting I met Max Grieshaber, a polymath, natural leader, and talented self taught artist. We teamed up to make banners for political demonstrations.

On weekends, I took the ferry to Staten Island, where Max lived in a beat up cottage with his brown dog Billy. After we hashed out design ideas, Max sketched them on paper; then roughed out the final image with acrylic paint on black cloth. I modeled the poses, or one of Max’s friends volunteered. Max painted the black and white banners in three or four days. Full color banners took weeks.

Where are they now? Scattered by winds to unheated attics, darkened closets, rolled or folded up, moth eaten or fading. Or perhaps not. Here is how and why we made them:

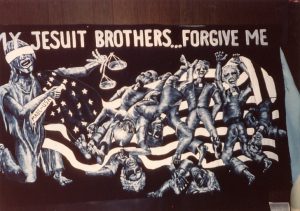

On 16 November 1989 Salvadoran Army troops in the Atlacatl battalion, a counter insurgency unit trained by the American’s at the School of the America’s, then located in Panama, murdered six progressive Jesuit priests, and their house keepers, at their university residence in San Salvador. CISPES took part in calling attention to the audacious crime. After a world outcry several low ranking officers were convicted, then later released. In 2016 senior officers involved in the massacre were extradited to face trial. Max and Medic finalized the banner over the course of an afternoon. Max spent many days painting it.

On 16 November 1989 Salvadoran Army troops in the Atlacatl battalion, a counter insurgency unit trained by the American’s at the School of the America’s, then located in Panama, murdered six progressive Jesuit priests, and their house keepers, at their university residence in San Salvador. CISPES took part in calling attention to the audacious crime. After a world outcry several low ranking officers were convicted, then later released. In 2016 senior officers involved in the massacre were extradited to face trial. Max and Medic finalized the banner over the course of an afternoon. Max spent many days painting it.

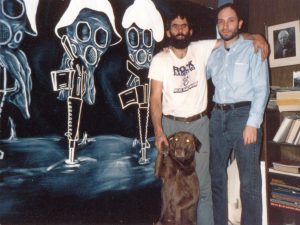

Likely one of our first efforts, Max, Medic and Billy pose for a photograph. Without words, the image was meant to portray anticipated American losses due to chemical or biological agents. In fact GIs were over kitted with clumsy gas masks and hazmat protective gear; many suffered from heat exhaustion. The first Gulf War, whose actual losses and crimes were suppressed by US media, lasted seven weeks.

Likely one of our first efforts, Max, Medic and Billy pose for a photograph. Without words, the image was meant to portray anticipated American losses due to chemical or biological agents. In fact GIs were over kitted with clumsy gas masks and hazmat protective gear; many suffered from heat exhaustion. The first Gulf War, whose actual losses and crimes were suppressed by US media, lasted seven weeks.

A fine example of Max’s artistic skills, he painted this banner while working aboard a dredging ship, then mailed it to Medic. Rather than clever political slogans, we preferred emotionally driven short phrases. The image depicts president George HW Bush cloaked in an American flag turned grave yard. The horizon burns with the names of countries invaded by the US.

A fine example of Max’s artistic skills, he painted this banner while working aboard a dredging ship, then mailed it to Medic. Rather than clever political slogans, we preferred emotionally driven short phrases. The image depicts president George HW Bush cloaked in an American flag turned grave yard. The horizon burns with the names of countries invaded by the US.

Wearing CVS Blu Blockers and sport jacket purchased at Good Will, Medic poses with the late Father Dan Berrigan at an anti-war demonstration in New York city. Through letters and poems Father Dan kindly stayed in touch with Medic for many years. He is much missed by all who knew him. Dan is best known for his participation in anti-Vietnam war and anti-nuclear protests. Less well know is that in 1968 Father Berrigan and historian Howard Zinn flew to Hanoi to receive the first three American POWs released by North Vietnam.

Wearing CVS Blu Blockers and sport jacket purchased at Good Will, Medic poses with the late Father Dan Berrigan at an anti-war demonstration in New York city. Through letters and poems Father Dan kindly stayed in touch with Medic for many years. He is much missed by all who knew him. Dan is best known for his participation in anti-Vietnam war and anti-nuclear protests. Less well know is that in 1968 Father Berrigan and historian Howard Zinn flew to Hanoi to receive the first three American POWs released by North Vietnam.

Although the US government denied the Gulf Wars were fought for oil, many citizens felt otherwise. This banner created by Max and Medic depicts two GIs clinging to an oil drum as they are swept up by a blood crested wave. Another GI has already succumbed. The initial US anti-war demonstrations brought hundreds of thousands of protesters into the streets. Medic recalls a New York city woman gasping at the sight of this emotionally charged banner.

Although the US government denied the Gulf Wars were fought for oil, many citizens felt otherwise. This banner created by Max and Medic depicts two GIs clinging to an oil drum as they are swept up by a blood crested wave. Another GI has already succumbed. The initial US anti-war demonstrations brought hundreds of thousands of protesters into the streets. Medic recalls a New York city woman gasping at the sight of this emotionally charged banner.

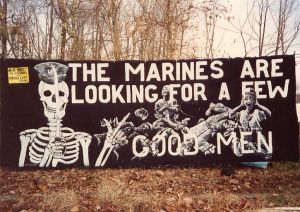

Hanging proudly on a clothes line in Max’s Staten Island back yard, this large banner took a several hours to design, and several afternoons to paint. Max used a medical text book to accurately draw the skeleton. Medic portrayed the soldiers in their various postures. Anarchists at an anti-war rally attempted to steal the banner but were successfully foiled.

Hanging proudly on a clothes line in Max’s Staten Island back yard, this large banner took a several hours to design, and several afternoons to paint. Max used a medical text book to accurately draw the skeleton. Medic portrayed the soldiers in their various postures. Anarchists at an anti-war rally attempted to steal the banner but were successfully foiled.

Where is Max now? According to an activists blog, not long ago he befriended a woman walking to raise funds for  Yassin Aref, a Kurdish refugee living in upstate New York, falsely accused by the FBI of terrorism. One of her walking companions was Max, who has created large banners used at Muslim solidarity rallies. As the blogger wrote, “Max is a man of many talents which are too numerous to list here, but this day my wife watched him regard a small herd of cows critically. He then made a low murmuring sound, and suddenly all the cows obediently (and apparently happily) responded to his call and walked up to greet him, switching their tails and lowing.”

Yassin Aref, a Kurdish refugee living in upstate New York, falsely accused by the FBI of terrorism. One of her walking companions was Max, who has created large banners used at Muslim solidarity rallies. As the blogger wrote, “Max is a man of many talents which are too numerous to list here, but this day my wife watched him regard a small herd of cows critically. He then made a low murmuring sound, and suddenly all the cows obediently (and apparently happily) responded to his call and walked up to greet him, switching their tails and lowing.”

Project SALAM (Support And Legal Advocacy for Muslims) exposes the legal, constitutional, and cultural consequences of preemptive prosecution of Muslims who have no connection to terrorism, and also advocates for their families.

Project SALAM (Support And Legal Advocacy for Muslims) exposes the legal, constitutional, and cultural consequences of preemptive prosecution of Muslims who have no connection to terrorism, and also advocates for their families.

The Banner Years

In 1987, while living in Astoria, New York, Medic joined CISPES, the Committee in Solidarity to the People of El Salvador, a grass roots organization opposed to US foreign policy in El Salvador. We meet weekly in Manhattan to discuss political developments, fund raising, and civil disobedience. CISPES also joined other grass roots efforts in opposing US foreign wars.

On weekends, I took the ferry to Staten Island, where Max lived in a beat up cottage with his brown dog Billy. After we hashed out design ideas, Max sketched them on paper; then roughed out the final image with acrylic paint on black cloth. I modeled the poses, or one of Max’s friends volunteered. Max painted the black and white banners in three or four days. Full color banners took weeks.

Where are they now? Scattered by winds to unheated attics, darkened closets, rolled or folded up, moth eaten or fading. Or perhaps not. Here is how and why we made them:

Where is Max now? According to an activists blog, not long ago he befriended a woman walking to raise funds for Yassin Aref, a Kurdish refugee living in upstate New York, falsely accused by the FBI of terrorism. One of her walking companions was Max, who has created large banners used at Muslim solidarity rallies. As the blogger wrote, “Max is a man of many talents which are too numerous to list here, but this day my wife watched him regard a small herd of cows critically. He then made a low murmuring sound, and suddenly all the cows obediently (and apparently happily) responded to his call and walked up to greet him, switching their tails and lowing.”

Yassin Aref, a Kurdish refugee living in upstate New York, falsely accused by the FBI of terrorism. One of her walking companions was Max, who has created large banners used at Muslim solidarity rallies. As the blogger wrote, “Max is a man of many talents which are too numerous to list here, but this day my wife watched him regard a small herd of cows critically. He then made a low murmuring sound, and suddenly all the cows obediently (and apparently happily) responded to his call and walked up to greet him, switching their tails and lowing.”