A collection of photo illustrated war and post war vignettes, short stories, war nightmares, war poetry and travel writing by a Vietnam combat medic. Site includes war related videos and documents. There is some harsh language.

At the Capital Hotel, an immense cinder block building located in the heart of Phnom Penh, the manager, a friendly middle-aged man, beckoned me to stifling cinder-block room with narrow bed and dripping sink.

“Three dollah, one nigh,” he said.

I immediately paid him, pocketed the key he provided, set my heavy pack on the chipped tile floor and slept for hours. My dreams were not pleasant.

Each morning on the adjacent street a dozen young Cambodian men with motorbikes vie to whisk backpackers wherever they wish to go. “Take me…take me…” they shout and wave as tourists drew near.

For some reason, I chose Elephant Man.

“OK…OK,” he said, motioning me to hop on behind him.

Burly and gruff, he told me the Khmer Rouge had killed most of his family, and he was lucky to be alive. Through snarled traffic and long open stretches he could not stop talking.

“Pol Pot no good,” he said as we pulled up to the entrance of a large flat field.

A sleepy teen aged boy, wearing thread bare shorts and flip flops, motioned us in. Elephant Man parked his bike and led the way.

“You look,” he said, pointing to several grassy pits.

Wherever I looked, scraps of faded cloth flecked the earth. It wasn’t possible, was it? The boy casually lay down beneath the shadow of a tall wooden tower filled top to bottom with hundreds of neatly arranged skulls and bones. In the war I had seen my share of fresh or putrid bodies, or bones poking up from shallow graves. I had watched and helped desecrate the dead. And consecrate ours. But not like this. Or was the boy inured or overwhelmed by it all, or simply tired from the noon day heat?

Elephant Man pointed to the horizon, his large hand sweeping left to right.

“More,” he said in a cold flat voice, as if the life had been squeezed from it. “Much more.”

I bought two Cokes from a rusting American soda machine. Both of us were sweating profusely and guzzled the icy drinks down.

After a time Elephant Man asked, “Where next?” but for several minutes I could not answer him.

“Capitol Hotel,” I finally said. “Tomorrow, Ministry of Information.”

“Why you want?” he asked, as I hopped on the bike. But I would not say.

Back at the hotel I ate a simple meal, toured a market, then fitfully slept for the next twelve hours. Early the next morning, off we went.

“OK…OK…” said Elephant Man, pulling up to an elegant building once used by the French.

I hopped off the Cub. “See you tomorrow.”

Elephant Man disappeared in a roar of blue smoke.

The Ministry of Information clerk, a gaunt man whose angular skull inhabited his broad Khmer face, whose thin white shirt hung from his body like a windblown leaf, whose thinning hair revealed clues of a near fatal event, in a purposeful, soft spoken voice, prompted, “You passport, please…”

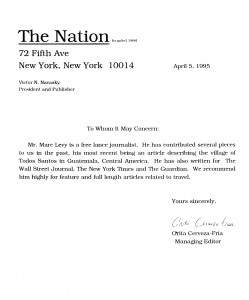

I offered him the document, a 2×2 inch photo of myself, and a counterfeit resume composed the day before on a computer at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club, once the refuge of international reporters covering the American war in Vietnam. The clerk inspected each item with deliberate care. I was a reporter, I told him. An obvious lie. But the media pass allowed extra time at Angkor Wat.

“One hour,” he said, pocketing the gifted cash. We shook hands. “One hour, s’il vous plaît.”

With the sun high overhead, the temperature rising, I decided to explore the narrow side streets which offered a bit more shade. Wandering about, I poked my head into small shops tucked into stucco buildings weathered delicate shades of red or blue. I smiled and waved to school children dressed in blue and white uniforms, their teacher dutifully chalking undulant Khmer script on ancient blackboards. At a French-built post office I bought stamps, tissue-thin aerograms, a laminate phone card made in Australia. I checked my watch and headed back to the Ministry of Information, where even the clerk sweated from the forceful heat.

“For you,” he said, handing me a green and white media pass encased in stiff transparent plastic.

Beneath the words Kingdom of Cambodia, the country’s motto: Nation, Religion, King. I nodded a silent thank you to this inscrutable man, took the coveted thing, give him a few dollars more.

He closed his eyes, pressed his palms together, and bowed slightly.

“Merci. Merci beaucoup,” he said.

His lips gathered to shape a smile. A survivor’s smile.

Then he was gone.

Year Zero: The Silent Death of Cambodia is a 1979 British television documentary film written and presented by the Australian journalist John Pilger, which was produced and directed by David Munro for the ITV network by Associated Television. First broadcast on 30 October 1979, the filmmakers had entered Cambodia in the wake of the overthrow of the Pol Pot regime.

The film recounts the bombing of Cambodia by the United States in the 1970s, a chapter of the Vietnam War kept secret from the American population, the subsequent brutality and Cambodian genocide perpetrated by Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge militia after their take over of the country, the poverty and suffering of the people, and the limited aid since given by the West.

Following the program, some $45 million was raised, unsolicited, in mostly small donations, including almost £4 million raised by schoolchildren in the UK. This funded the first substantial relief for Cambodia, including the shipment of life-saving medicines such as penicillin, and clothing to replace the black uniforms people had been forced to wear. According to Brian Walker, director of Oxfam, “a solidarity and compassion surged across our nation” from the broadcast of Year Zero.

During the filming of Cambodia Year One, the team were warned that Pilger was on a Khmer Rouge ‘death list.’ In one incident, they narrowly escaped an ambush.

In a 2007 speech Pilger described his experience with executives of the American Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). They refused to screen Year Zero, which, according to Pilger, has never been broadcast in the United States.

Kingdom of Cambodia

“Three dollah, one nigh,” he said.

I immediately paid him, pocketed the key he provided, set my heavy pack on the chipped tile floor and slept for hours. My dreams were not pleasant.

Each morning on the adjacent street a dozen young Cambodian men with motorbikes vie to whisk backpackers wherever they wish to go. “Take me…take me…” they shout and wave as tourists drew near.

For some reason, I chose Elephant Man.

“OK…OK,” he said, motioning me to hop on behind him.

Burly and gruff, he told me the Khmer Rouge had killed most of his family, and he was lucky to be alive. Through snarled traffic and long open stretches he could not stop talking.

“Pol Pot no good,” he said as we pulled up to the entrance of a large flat field.

A sleepy teen aged boy, wearing thread bare shorts and flip flops, motioned us in. Elephant Man parked his bike and led the way.

“You look,” he said, pointing to several grassy pits.

Wherever I looked, scraps of faded cloth flecked the earth. It wasn’t possible, was it? The boy casually lay down beneath the shadow of a tall wooden tower filled top to bottom with hundreds of neatly arranged skulls and bones. In the war I had seen my share of fresh or putrid bodies, or bones poking up from shallow graves. I had watched and helped desecrate the dead. And consecrate ours. But not like this. Or was the boy inured or overwhelmed by it all, or simply tired from the noon day heat?

wasn’t possible, was it? The boy casually lay down beneath the shadow of a tall wooden tower filled top to bottom with hundreds of neatly arranged skulls and bones. In the war I had seen my share of fresh or putrid bodies, or bones poking up from shallow graves. I had watched and helped desecrate the dead. And consecrate ours. But not like this. Or was the boy inured or overwhelmed by it all, or simply tired from the noon day heat?

Elephant Man pointed to the horizon, his large hand sweeping left to right.

“More,” he said in a cold flat voice, as if the life had been squeezed from it. “Much more.”

I bought two Cokes from a rusting American soda machine. Both of us were sweating profusely and guzzled the icy drinks down.

After a time Elephant Man asked, “Where next?” but for several minutes I could not answer him.

“Capitol Hotel,” I finally said. “Tomorrow, Ministry of Information.”

“Why you want?” he asked, as I hopped on the bike. But I would not say.

Back at the hotel I ate a simple meal, toured a market, then fitfully slept for the next twelve hours. Early the next morning, off we went.

“OK…OK…” said Elephant Man, pulling up to an elegant building once used by the French.

I hopped off the Cub. “See you tomorrow.”

Elephant Man disappeared in a roar of blue smoke.

The Ministry of Information clerk, a gaunt man whose angular skull inhabited his broad Khmer face, whose thin white shirt hung from his body like a windblown leaf, whose thinning hair revealed clues of a near fatal event, in a purposeful, soft spoken voice, prompted, “You passport, please…”

I offered him the document, a 2×2 inch photo of myself, and a counterfeit resume composed the day before on a computer at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club, once the refuge of international reporters covering the American war in Vietnam. The clerk inspected each item with deliberate care. I was a reporter, I told him. An obvious lie. But the media pass allowed extra time at Angkor Wat.

“One hour,” he said, pocketing the gifted cash. We shook hands. “One hour, s’il vous plaît.”

With the sun high overhead, the temperature rising, I decided to explore the narrow side streets which offered a bit more shade. Wandering about, I poked my head into small shops tucked into stucco buildings weathered delicate shades of red or blue. I smiled and waved to school children dressed in blue and white uniforms, their teacher dutifully chalking undulant Khmer script on ancient blackboards. At a French-built post office I bought stamps, tissue-thin aerograms, a laminate phone card made in Australia. I checked my watch and headed back to the Ministry of Information, where even the clerk sweated from the forceful heat.

“For you,” he said, handing me a green and white media pass encased in stiff transparent plastic.

transparent plastic.

Beneath the words Kingdom of Cambodia, the country’s motto: Nation, Religion, King. I nodded a silent thank you to this inscrutable man, took the coveted thing, give him a few dollars more.

He closed his eyes, pressed his palms together, and bowed slightly.

“Merci. Merci beaucoup,” he said.

His lips gathered to shape a smile. A survivor’s smile.

Then he was gone.

___________

The Killing Fields Museum

Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum

The Bophana Center

Elizabeth Becker

Year Zero: The Silent Death of Cambodia is a 1979 British television documentary film written and presented by the Australian journalist John Pilger, which was produced and directed by David Munro for the ITV network by Associated Television. First broadcast on 30 October 1979, the filmmakers had entered Cambodia in the wake of the overthrow of the Pol Pot regime.

The film recounts the bombing of Cambodia by the United States in the 1970s, a chapter of the Vietnam War kept secret from the American population, the subsequent brutality and Cambodian genocide perpetrated by Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge militia after their take over of the country, the poverty and suffering of the people, and the limited aid since given by the West.

Following the program, some $45 million was raised, unsolicited, in mostly small donations, including almost £4 million raised by schoolchildren in the UK. This funded the first substantial relief for Cambodia, including the shipment of life-saving medicines such as penicillin, and clothing to replace the black uniforms people had been forced to wear. According to Brian Walker, director of Oxfam, “a solidarity and compassion surged across our nation” from the broadcast of Year Zero.

During the filming of Cambodia Year One, the team were warned that Pilger was on a Khmer Rouge ‘death list.’ In one incident, they narrowly escaped an ambush.

In a 2007 speech Pilger described his experience with executives of the American Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). They refused to screen Year Zero, which, according to Pilger, has never been broadcast in the United States.

source: wikipedia