“Take five,” says the lieutenant.

I clear a spot, sit on my  pack, slug a half canteen of water.

pack, slug a half canteen of water.

“Hey, Doc,” says Larry Roy, “I don’t feel too good.” He dips his head, with his forearm, wipes his brow.

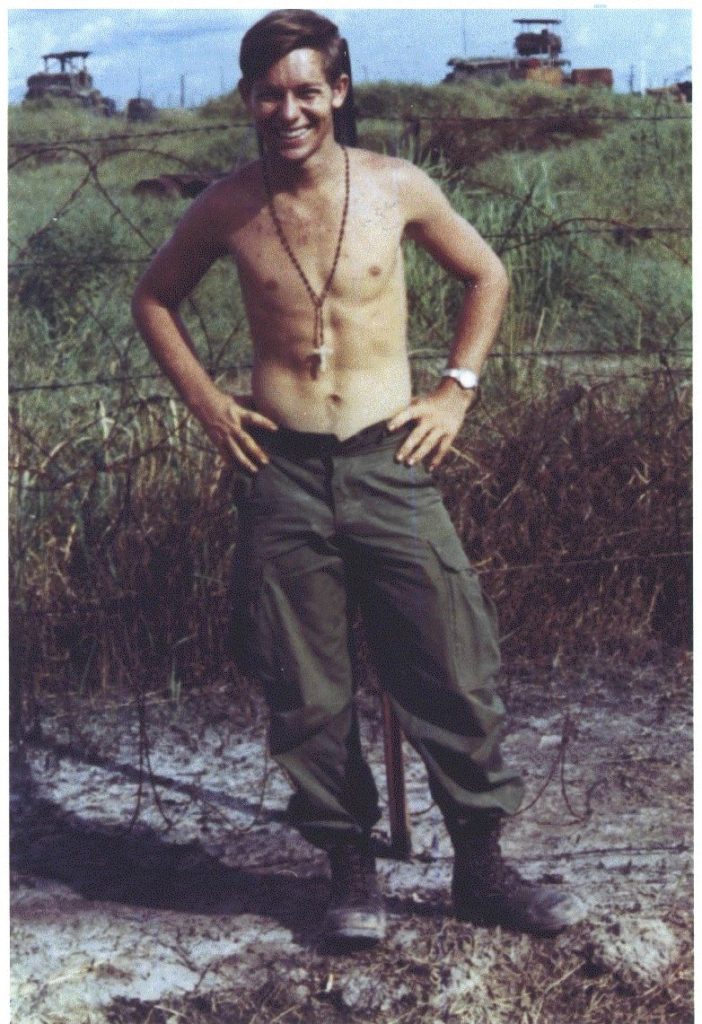

In another world, Larry Roy played golf. Here, at seventeen, he walks point. Everyone likes him. He smiles a lot. Maybe too much. But for Christ sake, not now, Larry Roy. Not now.

“What is it?” I ask in my best medic voice. “What’s the matter?”

His throat hurts, his stomach aches. He coughs and wheezes.

“Doc, I feel bad all over,” he says.

His temperature is one hundred and three. I open my canvas aid bag, hand him antibiotics, anti-spasmotics, muscle relaxants, analgesics, antihistamines.

“That ought to work,” I say, zipping the canvas bag shut.

Larry Roy eyes the brightly colored pills, pops the artificial rainbow into his mouth, unscrews the plastic cap of his canteen, tilts his head back, glugs down water.

“You’re all right, Doc,” he says. “Thank you much.” With the back of his hand he wipes his mouth. Then he is gone.

On patrol, as we trudge or crawl or snake our way through dense jungle, this ethereal world so deathly quiet, every grunt has his job. But the point is first to walk into the forbidding undergrowth, the beautiful groves of tall bamboo.

On patrol, as we trudge or crawl or snake our way through dense jungle, this ethereal world so deathly quiet, every grunt has his job. But the point is first to walk into the forbidding undergrowth, the beautiful groves of tall bamboo.

See him, slightly hunched, neck craning, M16 held at the hip, his eyes roving, searching for any hint of an ambush. Hear how his heart pounds like thunder inside his head. See how the sweat trickles from every pore of his body. Feel how it saturates his filthy uniform, how it clings to him, serpentine, like a second skin. Step by step, see how the pointman looks, listens, scents the air for tell tale signs of enemy passage. With each step, he pulses with dread, steadies his fear, plods forward, alive to the sudden thrill of combat, the lawless power it bestows upon him. Larry Roy lives in a world of absolute clarity, where every step may be his last.

An hour later he returns. His eyes are glazed. His speech, too slow. Too easy.

“Doc, whatever you did, man, I feel great!”

Two weeks later a doctor throttles me: “You could have  killed him. Don’t ever do that again.”

killed him. Don’t ever do that again.”

But the rest of that month went much the same. Cuts and scratches. Colds, parasites, fungal infections. Thankfully, no howling screams from gun shot wounds. No writhing grunts struck by withering shrapnel. No in-out or ripped apart or hemorrhaging trauma. No egg-splat-gray matter that won’t wash off. No blood or teeth or broken bones. This month, this blessed month, none of that.

_________________

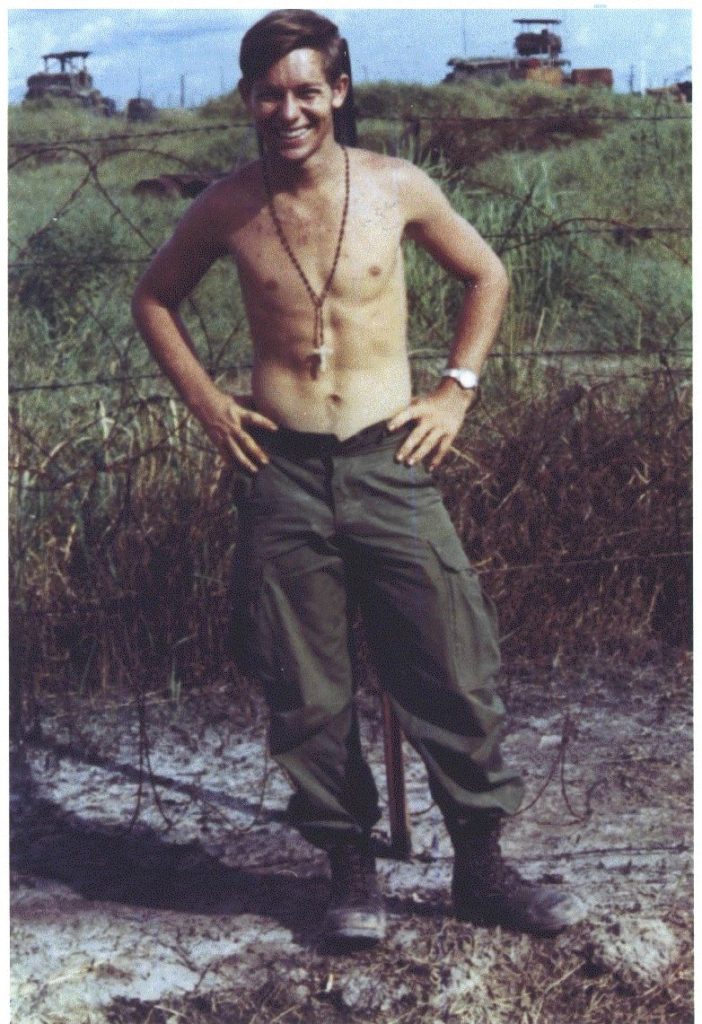

Top photo: New Years Day: After an ambush, third platoon celebrates three enemy dead, no American losses. Tay Ninh, 1970.

Easy Month

“Take five,” says the lieutenant.

I clear a spot, sit on my pack, slug a half canteen of water.

pack, slug a half canteen of water.

“Hey, Doc,” says Larry Roy, “I don’t feel too good.” He dips his head, with his forearm, wipes his brow.

In another world, Larry Roy played golf. Here, at seventeen, he walks point. Everyone likes him. He smiles a lot. Maybe too much. But for Christ sake, not now, Larry Roy. Not now.

“What is it?” I ask in my best medic voice. “What’s the matter?”

His throat hurts, his stomach aches. He coughs and wheezes.

“Doc, I feel bad all over,” he says.

His temperature is one hundred and three. I open my canvas aid bag, hand him antibiotics, anti-spasmotics, muscle relaxants, analgesics, antihistamines.

“That ought to work,” I say, zipping the canvas bag shut.

Larry Roy eyes the brightly colored pills, pops the artificial rainbow into his mouth, unscrews the plastic cap of his canteen, tilts his head back, glugs down water.

“You’re all right, Doc,” he says. “Thank you much.” With the back of his hand he wipes his mouth. Then he is gone.

See him, slightly hunched, neck craning, M16 held at the hip, his eyes roving, searching for any hint of an ambush. Hear how his heart pounds like thunder inside his head. See how the sweat trickles from every pore of his body. Feel how it saturates his filthy uniform, how it clings to him, serpentine, like a second skin. Step by step, see how the pointman looks, listens, scents the air for tell tale signs of enemy passage. With each step, he pulses with dread, steadies his fear, plods forward, alive to the sudden thrill of combat, the lawless power it bestows upon him. Larry Roy lives in a world of absolute clarity, where every step may be his last.

An hour later he returns. His eyes are glazed. His speech, too slow. Too easy.

“Doc, whatever you did, man, I feel great!”

Two weeks later a doctor throttles me: “You could have killed him. Don’t ever do that again.”

killed him. Don’t ever do that again.”

But the rest of that month went much the same. Cuts and scratches. Colds, parasites, fungal infections. Thankfully, no howling screams from gun shot wounds. No writhing grunts struck by withering shrapnel. No in-out or ripped apart or hemorrhaging trauma. No egg-splat-gray matter that won’t wash off. No blood or teeth or broken bones. This month, this blessed month, none of that.

_________________

Top photo: New Years Day: After an ambush, third platoon celebrates three enemy dead, no American losses. Tay Ninh, 1970.